Better together: the power of human connectedness

01Connectedness

From ICT networks to inclusive people management, a world divided is calling out for more human connectedness. Here’s how business leaders can forge the human connections on which our wellbeing depends.

Dysfunctional and divided. That was Tom Standage’s assessment of the world when The Economist editor appeared at IESE to present his annual forecast for the year ahead. Business leaders nodded along as he reeled off predictions that were already apparent: an uneven recovery from the pandemic that had distanced us and would continue to do so; inflation woes owing to broken supply chains; a climate crunch as policymakers put more energy into bickering than into solving the energy crisis itself; a new techlash as regulators try to rein in the fake news spewed by tech giants, which have polarized our societies and our politics to such a degree that coming together to get things done seems like a quaint concept from a bygone era. “We’re clearly at the end of a period of relative geopolitical stability that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union,” Standage proclaimed in February 2022. Later that month, Russia invaded Ukraine. Clearly indeed.

“The world tends to divide into separate technological and economic blocs,” notes IESE professor Xavier Vives. Embedded in that statement are two reasons for the division: technology and economics. For all the merits of digital innovation and globally linked financial success, our current panorama reveals something has gone awry. Perversely, the means to bring us closer together in the 20th century are instead driving us further apart in the 21st.

In business terms, this has led to the so-called Great Resignation – a phenomenon whereby tens of millions of workers, mainly in the U.S. but also elsewhere, are calling it quits. They’re dropping out of the workforce, or are at least leaving traditional workplaces behind, in search of something better. A McKinsey report expressed it thus: “Employees crave investment in the human aspects of work. Employees are tired, and many are grieving. They want a renewed and revised sense of purpose in their work. They want social and interpersonal connections with their colleagues and managers. They want to feel a sense of shared identity. Yes, they want pay, benefits and perks, but more than that they want to feel valued by their organizations and managers. They want meaningful interactions, not just transactions. By not understanding what their employees are running from, and what they might gravitate to, company leaders are putting their very businesses at risk.”

51% of employees who left their job in the past six months said they did so because they lacked a sense of belonging

46% gave as a reason to quit, their desire to go and work with people who trust and care for each other

SOURCE: McKinsey “Great Attrition” survey of Australian, Canadian, Singaporean, British and American workers

This stark reality caught the attention of IESE Dean Franz Heukamp, reminding him of something Harvard’s Michael Sandel said during IESE’s Global Alumni Reunion: We are most fully human when we contribute to the common good, when we are needed by – and connected to – those with whom we share a common life.

“If the pandemic has taught us anything, it’s that we live in an interconnected world where our wellbeing depends on others,” Heukamp wrote in a recent post. “I’m optimistic by nature, so when I see how disconnected we are, it only reinforces my belief in the importance of meaningful connections and in the power of business leaders to forge those connections. Changing the way we treat each other is something any of us can do, starting today.”

In this special report, we draw on research by IESE professors and others into the concept of connectedness – starting with the ICT networks and communal infrastructures that link us, before delving into the implications for our organizations, workplaces and people management. In doing so, we highlight some of the practical ways that we can all work together to help heal our divisions and elevate human relationships, which should be at the center of everything we do.

Tech connectedness

Perhaps nothing has revolutionized our connectedness over the past decade more than digital platforms. As indicated by the name “sharing economy,” peer-to-peer digital platforms have been hailed for their ability to put disconnected people in touch with each other to share idle or underutilized resources, transforming the nature of value creation by monetizing the efficient connection of supply and demand.

However, for all their positive features, these platforms have also generated negative externalities. For example, Airbnb let local residents connect with tourists to offer them accommodation; but in popular cities like Barcelona, this led to a situation where local residents were shut out of the housing market as apartment rentals were taken over by tourists, and the residents who remained saw their neighborhoods degraded by overtourism. We now see grassroots movements of local citizens united against these platforms.

For all their positive features, these platforms have generated negative externalities

The growing resistance to digital platforms is the focus of research by IESE’s Joan E. Ricart and Pascual Berrone, with co-authors Yuliya Snihur and Carlos Carrasco. In their paper published in Strategy Science, they analyze when collective resistance is more likely and, knowing this, how digital platforms can then mitigate that resistance through what they call “relational business model design.” In other words, when too much connection tips over into disconnection, the antidote is to reconnect with local stakeholders and enlist them in ecosystem-centered governance.

The authors classify three types of digitally enabled platform business models based on: 1) physical assets (as with Airbnb or goods exchanges like eBay); 2) digital assets (music or movie streamers like Spotify or Netflix); and 3) labor assets (delivery services like Glovo). Resistance can come from two sources: 1) local non-participants/outsiders (those who don’t use the platform but are affected by it); and 2) local participants/insiders (those who do use the platform, relying on it for income or other resources, and therefore have a role in affecting it directly).

For outsiders, the likelihood of resistance goes up when physical assets are highly localized and scarce. For insiders, they are more likely to voice grievances when the digital platform leverages highly localized and precarious labor.

The features that make digital platforms a disruptive force – direct connections, self-organization, network effects, winner-takes-all dynamics – are the same ones that disgruntled insiders and outsiders can exploit to formalize their collective resistance. This happened in Barcelona when citizen groups and neighborhood associations mobilized online and organized a march through the city streets to protest against overtourism. U.S. rideshare drivers did something similar against Uber and Lyft concerning pay and lack of worker protections.

Business leaders need to think again about their fundamental business model design

To deal with this, business leaders need to think again about their fundamental business model design, which is a direct reflection of how a firm wishes to treat outsiders as well as its insiders. Such platforms are typically double-sided, meaning the firm acts a broker bringing two sides – users and providers – together, collecting revenue from one or both sides for enabling the transaction.

Alternatively, firms ought to adopt a multisided model, one that includes other stakeholders, such as city hall and neighborhood associations, as part of their value proposition. They need to connect with local outsiders as much as they do local insiders. Uber providing accident insurance, and Airbnb encouraging its hosts to offer short-term stays to refugees in partnership with local resettlement agencies, exemplify how firms can extend value to other stakeholders, reducing some of the us-versus-them mentality and demonstrating good citizenship.

This needs to extend to the firm’s governance mechanisms. So, beyond the usual pricing agreements and rating systems, the firm should consider sharing data with cities to help local planning, and vetting systems based on fairness and common interests, rather than merely making more money for insiders. This can help digital platforms restore their broken community relations.

Real connections to combat fake news

Another area of tech that has led to societal breakdown concerns social media. It’s no coincidence that Oxford dictionary’s word of the year for 2016 was “post-truth” – the same year of the Brexit referendum in the U.K. and the election of Donald Trump as president of the U.S. Both events were likely influenced by social media-fueled (dis)information activities, when “fact and fiction became hard to tease apart,” said IESE’s Massimo Maoret in a TEDxIESEBarcelona talk on “The Social Construction of Facts: Surviving a Post-Truth World.”

Maoret’s research focuses on the social creation of culture and how social networks impact performance, innovation and organizational socialization (see Network Connectedness). Through his analyses of social networks, he argues that tech isn’t exclusively to blame for the phenomenon of “fake news” as much as it has merely turbocharged something that has always been around.

Maoret explains: “Pre-web, the social process of building shared realities was curated and controlled by intermediaries – newspaper editors, academic and scientific bodies, the State and other such institutions – because the transaction costs of coordinating and disseminating information person-to-person were too high. But the digital revolution lowered or eliminated transaction costs, stripping power away from intermediaries and empowering individuals to connect directly with each other and to procure information cheaply for themselves from unfiltered sources.”

While this has democratized information, the lack of filters also means the subjective socio-cognitive biases through which humans interpret reality have been let off the leash, leading to a situation that is much more chaotic. “When individual ideas become connected, they become an inter-subjective shared reality, allowing people to co-construct a new social reality through the same, sometimes distorted, lenses. And when individuals are fully embedded in their own reality, this becomes a self-reinforcing echo chamber, which can veer quite dramatically away from others. This is why certain groups end up believing fanatically that the Earth is flat, that vaccines do not work, or that Russia has not invaded Ukraine. These processes are so powerful that they can happen to any of us.”

It requires connecting with others on a personal level, others who don’t think exactly like you

To defuse these dangers, Maoret says each one of us must stop being a passive recipient of news and information, and instead become active fact-checkers, recognizing the power – and responsibility – we hold through our amplified web of connections to shape reality, for good or bad.

“Question more and believe a little less,” he urges. “Would you ever take a used-car salesman at face value? Probably not and for good reason, because this person clearly has an agenda. By the same token, why blindly trust the information on Twitter or Facebook? We should be at least as critical, particularly when items are obvious clickbait or too good to be true. That should be an instant red flag! We must actively search more to find the truth. This means recognizing that every single source is biased in some way, and the only way to remove that bias is to cross-check more sources. If you speak more than one language, read how media from different countries treat the same news, and triangulate that information. You may never get the full truth, but you may get a better-informed opinion. The more different points of view you have, the better.”

Above all, it requires connecting with others on a personal level – “others who don’t think exactly like you,” says Maoret, “and engaging with them in a positive manner, not simply to prove them wrong. Give others the benefit of the doubt. Be open to be proven wrong, which is great because it means you just learned something. And by connecting with different people and having genuine, open conversations, we will hopefully lower the negative impact of fake news on our lives.”

Where’s the humanity?

All this discussion should underscore a key point: For all the affordances of tech connectedness, we must never forget that the human component must be kept central. As with the application of ICT in urban environments, if there is no clear notion of why we are using the tech nor for what larger purpose, then likewise employing tech in people management will be just as counterproductive. So states a report on Technology and HR by Joan Fontrodona, holder of the CaixaBank Chair of Sustainability and Social Impact at IESE.

“Tech connectedness is never an end in itself,” he writes, “but a tool to help companies reaffirm the basic function of management, which is the personal and professional development of people within a corporate framework. Indeed, it is worth adding that the human is never a ‘resource.’ Although ‘human resources’ is the universal term, my hope is that, sooner rather than later, this designation would be replaced by another that unambiguously emphasizes the centrality of the human – not as an adjective but as the subject. In the world of work, as in any other context, we must consciously resist the potential depersonalization of labor to ensure that personal human relationships are always given the priority they deserve.”

Everyone working remotely has workers saying they now feel, well, remote from their coworkers

Here, we shift our discussion to the workplace, which, like the world at large, has been characterized by disconnection lately. One of the downsides of the pandemic forcing everyone to work remotely has been workers saying they now feel, well, remote from their coworkers. And as a Harvard Business Review article noted, those feelings of disconnection are translating into higher turnover, lower productivity, more absenteeism and lower quality of work, whereas the opposite is true of employees who say they feel a real sense of belonging. The takeaway? It’s more important than ever to create the conditions that promote meaningful connection at work.

It starts, as Fontrodona explained, by getting our priorities straight. Everyone says, “People are our greatest asset,” yet how many actually believe it and put it into practice? In this sense, it’s worth revisiting the timeless teachings of the late Juan Antonio Perez Lopez.

Reconnecting our divided societies

The teachings of the late Juan Antonio Perez Lopez have a lot to offer, as John Almandoz explains.

Preparing for a conference on the legacy of the late IESE professor and dean Juan Antonio Perez Lopez (1934-1996), I came across an old teaching note in which Perez Lopez foresaw the potential “social disaster” of the free-market system unless a “control mechanism” could be found – one that treated personal flourishing and social order on a par with corporate prosperity. Given the growing trend of putting purpose at the heart of business, the business world finally seems to be catching up with his ideas.

Perez Lopez reminds us that people are not merely self-interested, driven by material wants, but also social beings, driven by intrinsic motives and transcendent needs. These transcendent needs can only be satisfied by contributing to the welfare of others. For Perez Lopez, good leadership involves not only attaining business results but also developing and building people, one by one, and uniting an organization toward an inspiring purpose of serving people and society in its daily operations. This kind of leadership is transformative for managers, resulting in greater unity and cohesion throughout the organization.

This model of the firm is not only better than the neoclassical alternative, but it may also be the best hope we have to mend the future for a world in need of transformation. As business leaders, we should seek to reconnect people. And even when we fall short of the ideal, we will still be better off for having tried.

John Almandoz holds the newly created Juan Antonio Perez Lopez Chair, contributing research on human action in companies, based on the theories of Perez Lopez.

IESE’s Antonio Argandoña, writing in La empresa, una comunidad de personas (The company, a community of people) draws upon Perez Lopez’s wisdom when he calls for ethical people management: “Managers should create spaces where employees feel trusted. Believe in your team. Give them responsibility and resources. Avoid constant checks and micromanagement. Allow them room to err and offer constructive criticism. This makes it easier for employees to connect with the organization and enjoy harmonious, collaborative working relationships, as they should. Such workplaces encourage each person to offer up the best of themselves – to the company, to customers, to colleagues, to society.”

Connecting global talent

As mentioned, COVID-19 occasioned a dramatic drop in physical global mobility as individuals, whether expatriates or global business travelers, suddenly pivoted to virtual global work. Instead of moving people to work, work moved to people.

According to a paper by IESE’s Sebastian Reiche et al. published in the Journal of Global Mobility, virtual global mobility, or VGM, is a trend that’s here to stay. Not flying your executives around the world to attend a meeting at a moment’s notice is certainly more cost-efficient; and the new development and deployment of ICT “could generate revenues by creating new business opportunities,” not to mention giving workers more choice, state the authors. However, they add that VGM could imply “profound changes in working patterns, talent development investment and recipients, as well as possible changes in organizational power structures over time.”

For example, one of the benefits of face-to-face meetings was to help foster connections between headquarters and host country employees, building trust and shared group norms. If VGM supplants that, then multinational companies must figure out how they will ensure the same familiarity with corporate policies and the necessary transfer of managerial expertise, specialized technical know-how and professional training that was previously served by corporate expatriates on short-term assignments. Companies may well need to implement some hybrid form of global work in order to maintain the requisite level of connectedness on which their competitive strategic advantage depends.

Tips for better VGM

Time zone preferences Try to accommodate team member preferences for connection times, and ensure the “suffering” of connecting at unsociable hours is shared equally.

Rules of engagement Set clear expectations for videoconferencing: when you’ll communicate and how, e.g., rephrasing what was said, summing up what was agreed, recording calls.

Trust your team Focus on outputs (“Please deliver x by z”) and then let them get on with it without constantly checking up on them.

Overcoming emotional distance Encourage informal conversations. Ask people about their needs. Be positive, uplifting and hopeful. Kids or a cat jumping into the frame is not any reason to apologize but an opportunity to connect with colleagues, conveying one’s personal life and identity.

Connecting cross-culturally

Another requirement to maintain effective global leadership is the ability to connect with people from different cultures. Global leadership, by definition, entails leading across cultures from which arises the challenge of how to view difference, how to manage difference, and how to bridge differences and create cross-cultural connection, as research by IESE’s Yih-Teen Lee consistently shows.

In “Connecting across cultures” published in Advances in Global Leadership, Farah Y. Shakir (IESE PhD) and Lee interviewed numerous multicultural leaders and found that certain identity-defining experiences helped give rise to three specific qualities which better enable individuals to connect with people from different backgrounds:

- An early experience of feeling like an outsider can develop empathy toward others also considered outsiders. This creates emotional connection with others.

- Discovering your own identity in relation to the rest of society requires perspective-taking. This entails learning about other cultures and weighing commonalities among differences, which creates cognitive connection.

- With confidence in one’s own identity comes the ability to maintain core values when taking on local perspectives. This quality of integration creates behavioral connection in a spirit of collaboration.

The authors recommend that these three dimensions be incorporated into global leadership development, going beyond a shallow list of cultural traits to instead focus on meaningful behaviors. As they explain in their paper, “Many cultural training programs fail because they tend to put too much emphasis on culture-specific knowledge. Simple stereotypes about national cultures do not prepare people for culturally complex situations.”

Shakir elaborated on this point in a TEDxIESEBarcelona talk. Drawing on her own story as a Pakistani-Canadian with a unique mix of backgrounds, she shared her own identity-defining experiences of when she had felt like an outsider. “We live in a world which is overshadowed by warfare and economic extremes, illustrating just how far we are from connectedness. How can we reach a meeting point in such conflicting times?”

How can we reach a meeting point in such conflicting times?

For organizations, it demands fostering activities that generate emotional, cognitive and behavioral connections, and environments “where there is a real sense of belonging, where people feel respected and included, regardless of their backgrounds. When people are acknowledged for who they are, it removes distractions, leading to their full potential.”

On the personal level, Shakir challenged each and every individual “to speak to someone who looks different or speaks differently. It’s a powerful ability we each have to make another person staring in from the outside to feel connected and accepted.”

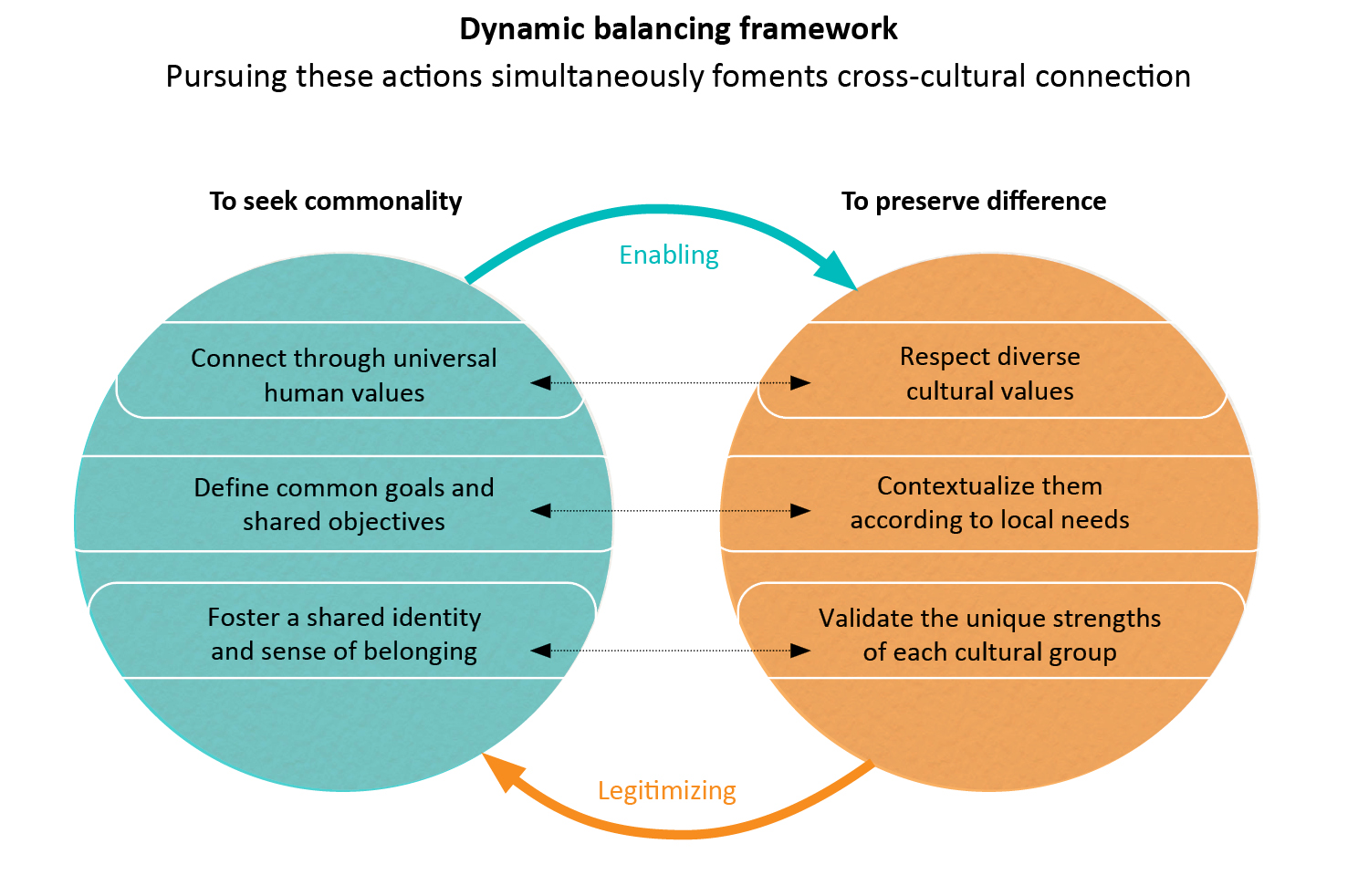

Building on these ideas, in other research with the University of Michigan’s Shawn Quinn, Lee elaborates a “dynamic balancing framework” for leading across cultures. Their framework blends the ancient Chinese concept of duality with modern theories of ambidexterity, in keeping with the nature of cross-cultural connection, which requires paying attention to commonalities while simultaneously recognizing and respecting differences.

To seek commonality, the authors recommend that managers should:

- establish relational connections through universal human values like love, caring and respect;

- define common goals and shared objectives;

- foster a shared identity that gives everyone a collective sense of psychological ownership and belonging.

At the same time, to preserve difference, managers should:

- understand and respect the values and behavioral norms that are different from the common ones;

- contextualize common goals and objectives according to local needs;

- validate the unique qualities, strengths and identities of each cultural group underneath the common umbrella.

The commonality actions enable preserving difference, just as preserving difference legitimizes our commonality. Such complementarity speaks both to the dynamic nature of the framework as well as to the delicate balance that must be struck to pursue both agendas concurrently.

“In my view, the most critical task for leaders today is cross-cultural connectedness,” says Lee, “which can be achieved by connecting with people at emotional, cognitive and behavioral levels – always being mindful of the ‘dynamic balancing’ involved in doing so.”

Connecting our diversity

When inclusion is not achieved, you end up with in-groups and out-groups; rather than being a unifying force, identity is used as a wedge. Left unaddressed, employees may feel the only way to overcome the disconnection they feel at work is to quit their job and go off and work on their own terms. Indeed, many entrepreneurs cite frustration with their former employment as one of the motivators for launching their own business. If this is so, what happens when you remove those frustrations?

Knowing that discrimination and being made to feel like an outsider are key factors in workers leaving a company and knowing that a diverse workforce has long been associated with multiple firm benefits, IESE’s Giovanni Valentini decided to explore the effect of antidiscrimination legislation on entrepreneurship. Specifically, he studied the U.S. Employment Non-Discrimination Acts, whose staggered rollout enabled him and his two co-authors to compare the effects of minority employee protection in 15 states that had enacted the legislation with states that had not, over the course of several years.

Does protecting oppressed groups from workplace discrimination have a noticeable impact on entrepreneurship?

So, does protecting traditionally oppressed groups – members of racial minorities or, most recently, the LGBT community – from workplace discrimination have a noticeable impact on entrepreneurship? Yes, according to their paper published in the Strategic Management Journal, though perhaps not in the way one would think. The paper puts forward that the antidiscrimination laws lead to relatively fewer startups but they are of higher quality, controlling for other factors.

Many public policies promote entrepreneurship to create jobs, but not all startups are created equal: some end up squandering resources when they fail. That is one reason why Valentini’s research looked at measures of startup quality: survival rates after five years, the amount of venture capital invested, and the number of patents awarded. For these three variables, his results were clear: the relatively fewer startups created after antidiscrimination laws were passed were of significantly higher quality compared with those of the control groups. “We think it’s better to have higher quality startups because they can ultimately create more and better jobs,” Valentini says.

What he sees going on is that fewer people are forced to become entrepreneurs because discrimination on the job had limited their options. If more people feel welcome in an organization, they can positively contribute as part of a unified workforce.

For business, “we believe there are clearly more pros than cons when diversity is encouraged,” he says, emphasizing that, when it comes to antidiscrimination, moral reasons win out over the business case. “Diversity is a positive value in and of itself; antidiscrimination laws are a good thing, because discrimination shouldn’t happen.”

Connected for the future

“Whatever our activity, we should always approach it with an awareness and appreciation of our deep connection with others: we do not do it alone but in dialogue, in co-creation, with others.” So remarked Maria Iraburu Elizalde on her historic appointment as the first female president of the University of Navarra. “Adopting this connectedness mindset is transformational and generates a chain reaction for future generations. What inheritance do we want to pass on to them? After all, we do what we do for the sake of those who come after, for the positive social impact we will leave behind, for and with the help of others.”

Network connectedness

02Connectedness

Research-based tips for reaping the rewards of working together.

Question: Which positions in an organization have the greatest impact on incremental innovation productivity?

These individuals act as innovation “engines”

Individuals who work in a core R&D lab AND who are also at the core of the informal knowledge-sharing network (aka core/core) have the highest innovation productivity (measured as the number of product developments and incremental innovation improvements).

BUT core/core individuals whose knowledge-sharing ties are disproportionately toward colleagues located in the network periphery reap fewer benefits.

The benefits are mutually reinforcing in two aspects…

1 Access and control over resources from belonging to a core unit

2 Legitimacy and social support from being core in the informal network

TIPS

1 Identify core/core employees.

2 Shield them: Core/core employees, by being more in demand, might spread themselves too thin.

3 Keep them focused on other core colleagues, without neglecting less-central individuals.

4 Move core individuals in peripheral units to the core.

5 As network ties reconfigure, protect and nurture new cores.

SOURCE: “Big fish, big pond?” by Massimo Maoret (IESE), Marco Tortoriello (Bocconi University) and Daniela Iubatti (SKEMA Business School) in Organization Science.

Question: How to amplify and extend cooperative behavior and collaborative performance when working together on a shared project?

1. Encourage proximity*

*Based on a study of two regional offices that relocated to a single site.

Physically Reducing physical distance improves the collaboration effectiveness between employees.

Relationally Sitting closer stimulates communication, reciprocity and cooperation.

Affectively Strong affective closeness, developed from investing time and energy in the working relationship, mediates and strengthens the positive effects.

SOURCE: “Close to me: studying the interplay between physical and social space on dyadic collaboration,” Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings, by Massimo Maoret (IESE).

2. Normalize helpful behavior*

*Based on a study of researchers who worked together on journal articles and then one of the members left.

When triads (three individuals) behave in a helpful manner toward each other – providing intellectual or material support without expecting anything in return – the collaborations last longer, possibly through a micro-environment of shared identities, understandings and norms that mediates conflicts, creates a sense of belonging, and shifts interests and incentives away from individuals and toward the common interests of the group.

When 3rd party ties are weak i.e., parties monitor each other but no real helpfulness or cooperative norms exist – the connection won’t last when the 3rd party leaves.

However, when 3rd party ties are strong i.e., where cooperative norms also shape behavior – collaborations tend to persist. Helpful 3rd parties make their collaborators more helpful and better able to withstand conflict, even if the 3rd party is absent.

SOURCE: “Helpful behavior and the durability of collaborative ties” by Sampsa Samila (IESE), Alexander Oettl (Georgia Tech Scheller College) and Sharique Hasan (Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business) in Organization Science.

Where is your third space?

04Connectedness

Sanjali Nirwani (IESE MBA ’14) is Founder and CEO of Unlocked India.

A need for offline activities and post-pandemic reunions with family and friends is fueling a boom in board games, reported The Guardian. After two tough years, people are ready to reconnect, which is good news for Sanjali Nirwani who combined her keen interest in social entrepreneurship, travel, food, board games and cultural exploration into a high-concept café in her native country of India. In doing so, Nirwani is tapping into a pursuit as old as time: Archaeologists have dug up board games dating back millennia, with the most recent find being a 4,000-year-old stone board game in Oman that may be an antecedent to another ancient Middle Eastern game believed to be a precursor to backgammon. The universally enjoyed experience of playing a board game is one aspect of a “third space” – a metaphorical or physical place where human relationships and meaningful bonding are prioritized, making everyone a winner.

Here, Nirwani explains what connectedness means to her, based on a talk she gave at a TEDxIESEBarcelona event organized in 2021 on the theme of “The future of relationships.”

Where are you from? I often get asked this question. The answer is tricky. I was born in India, but I moved around a lot. I have lived in 15 cities and traveled to over 33 countries. Sometimes, I simply say I’m Indian; other times, I may say I’m a citizen of the world. As a young girl, I developed a sense of exploration. New places and new friends excited me, although every time I moved, there was also a displacement of identity.

Looking back now, I realize I grounded my sense of identity in what sociologists call “the third space.” The first space is your home, the second space is your workplace or educational institution, but the third space is where you enhance the relationships and connections that anchor you when your first space and second space are in a constant state of flux; these relationships and connections make life worth living.

The third space could be anyplace: a café, a bar, a place of worship, a bookstore, a hobby; it could even just be a feeling or a state of mind. For me, as a girl, it was playing team sports: not just playing the sport itself but the banter and camaraderie around it; those moments when real connection was formed. Later, when I moved to Barcelona to study at IESE, it was relating with my classmates. We were a group of strangers coming from all around the world – Germany, Jamaica, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, the United States, to name a few – but it didn’t matter where we had come from, we all connected, particularly outside of class over a board game.

The Settlers of Catan is a strategy board game that some might say is responsible for destroying friendships more than for making them, but when we played, there was a real sense of being part of something bigger that went beyond superficial interactions to something much deeper. The third space.

“We want to celebrate togetherness, with games to bring you closer to the people you’re with”

A few years later, while working in Amsterdam, everyone used to go to a bar located below the company headquarters. We would meet there every Friday. Suddenly, it wasn’t just “Michelle or Lucas from the 10th floor” but a real person with real stories to share. I remember having long, philosophical conversations with the CEO of the company, someone way higher up than me, but in that bar we were just two humans connecting. We ate bitterballen – Dutch croquettes – which connected us to the culture of the place itself. These were little experiences that helped form who I am today. The third space.

In Yuval Noah Harari’s book Sapiens, he talks about what distinguishes humans from, say, chimpanzees or other animals on the planet. We may not be the strongest species, yet we dominate the world chiefly for our ability to imagine fictional realities, to tell stories and believe them to be true.

Storytelling cultivates emotional connection – a sense of empathy and togetherness. Neuroscientists have found that a good story activates the brain as if you are actually experiencing for yourself what the other person is telling you. Oxytocin – the “feel good” hormone – is released. We are motivated to engage in prosocial behavior.

All of these ideas and experiences were in my mind when I decided to use my entrepreneurial abilities to launch my own humble venture – a third space for cultivating connectedness – in India in 2017. Unlocked is the first of its kind space with one of India’s largest libraries of board games, an international cuisine restaurant and an escape room. From the minute you walk through the door, it’s like entering a game or a puzzle. We want to transport people to another dimension, to celebrate togetherness, with games to bring you closer to the people you’re with, be they friends, family, colleagues or even strangers.

A typical day would see a family spanning three generations, a few groups of millennials, some couples and some gaming enthusiasts, all with one thing in common: no cell phones, lots of laughter, and true bonding over food and games in a good old-fashioned way.

“Today, we live in a world of strangers. Let’s try to change that”

A hundred years ago, my grandfather spent his entire life in one community where everybody knew him. The concept of a stranger was, well, strange. Today, we live in a world of strangers where we hardly even know our next-door neighbor. Our societies have become individualistic. Technology has made relationships more complex and increasingly transactional. A plethora of dating apps gives a sense of unlimited options but no real connections. Being an influencer on Instagram, where your social media life may be completely different from reality, is a career option. Our attention spans have been reduced to 15-second TikTok videos.

I recently read an article that said it takes only seven seconds to form an impression of someone you meet. The thought of this is mind-boggling: We are essentially judging people all the time. Whenever you meet someone new, you are essentially giving them an instant tick of yes or no. I sometimes wonder if my future children or grandchildren will be so immersed in technological relationships that they will forget how to socialize with someone over a drink or a board game. Let’s try to change that.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, we were all forced into lockdown. For me, as an explorer of spaces, what was most fascinating to witness was that, during that time, the first space and the second space merged. Our living rooms became our offices, our schools and even our socializing spaces, with Zoom birthday parties or game nights. It was during that time that the existence of the third space was under threat.

As COVID restrictions ease up, the need to preserve the third space becomes even more important. As the world opens up, I would encourage everyone to go out into your communities and create offline spaces – to form real relationships. When things get bad, remember the Italians, singing and dancing on their balconies, and use your own imagination to create a community around a shared passion. We can be socially distanced yet still together.

The next time you go to your favorite restaurant or your usual café, look at it with fresh eyes. Reflect back on your own life: Where is your third space? When were those times when you stepped off the hamster wheel and were truly present with and for other people? Be mindful of that space, and nurture the relationship with yourself and with those around you.

WATCH: Sanjali Nirwani speaks on “Building meaningful relationships in a world of strangers” during TEDxIESEBarcelona 2021.

READ ALSO: “Your move: how chess gives strategies for life” in IESE Business School Insight no. 158.

What kind of role model are you?

05Connectedness

How can a Top Management Team (TMT), through their own behavior, set the tone for an organizational climate of connectedness and enhance employee wellbeing?

This is a question that I have explored for years in a series of studies and, in the face of current challenges, it has gained new momentum.

In this edition of IESE Business School Insight, the importance of connectedness has been highlighted from different perspectives, all with the common conclusion that it is something positive for both individuals and organizations.

As a role model for organizational behavior, TMTs (i.e., boards and senior leadership teams) are in a position to set the stage for how they want people to interact and connect. People look up to these managers and interpret their behavior as a sign of what is expected and legitimate. Therefore, while some may believe that what happens in the boardroom stays in the boardroom, my research suggests otherwise. What we see is that the behavior of the TMT trickles down in the organization as a whole and, as such, may shape the behavior of everyone else, for good and for bad.

In a new study published in Long Range Planning, Simon de Jong (Maastricht University), Heike Bruch (University of St. Gallen) and I surveyed the board members, middle managers, employees and HR professionals of 100 organizations. In a previous study, we had demonstrated that a high level of intra-TMT connectedness – measured by what we called “behavioral integration” – related to a more positive organizational climate. In this new study, we demonstrate an even more profound effect: The absence of TMT cohesion and connectedness relates to a more negative and corrosive organizational climate. This means that connectedness in the boardroom – or the lack thereof – has direct implications for connectedness in the organization as a whole.

People have a basic need for human connectedness and may seek employment elsewhere if such basic needs are not met

We also observed direct consequences of a more positive vs. more corrosive climate for the wellbeing of employees, in terms of job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Working in a climate of productive collaboration makes employees more satisfied and less likely to leave. A corrosive climate, however, increases the chances that people will leave.

These findings underscore a point made elsewhere in this report: that people have a basic need for human connectedness and may seek employment elsewhere if such basic needs are not met. With scarcity of talent plaguing many countries and industries, no one can afford not to pay close attention to how their organizational climate may be helping or hurting the satisfaction and wellbeing of employees.

While top managers generally see the advantages of connectedness and teamwork at the top, it is not so easy to implement it. A leadership mindset of one-captain-on-a-ship, beliefs about the type of personalities that make it to the top, and fears of endless debates and conflicts among opposing interests may all stand in the way of developing true teamwork at the top.

Yet, in the face of our current geopolitical challenges, ongoing concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath, as well as trends for more decentralized, team-based, agile organizations, it’s worth the effort to ensure that TMTs can adequately thrive in the new reality.

The skills to make teamwork and connectedness in the boardroom a living reality include:

- the ability to communicate about the TMT’s internal dynamics;

- being disciplined about complementary roles and responsibilities;

- selecting senior managers with the drive and ability to thrive in building human connections.

Above all, one must accept that building and maintaining relationships take time and dedication.

How prepared are you to invest in your top team relationships?

Anneloes Raes is Associate Professor in the Department of Managing People in Organizations and holder of the Puig Chair of Global Leadership Development at IESE.

This Report forms part of the magazine IESE Business School Insight no. 161. See the full Table of Contents.

This content is exclusively for individual use. If you wish to use any of this material for academic or teaching purposes, please go to IESE Publishing where you can obtain a special PDF version of this report as well as the full magazine in which it appears.