Space, the new frontier: The future workplace

01Space, the new frontier

In 2015 Verizon was at a crossroads. For 50 years, the telecom’s growth had been driven by its landline business, for which it had accumulated a large portfolio of real-estate assets – 60 percent of which were small and medium-sized offices – spread across the United States. But as landlines gave way to wireless, nearly half of Verizon’s real estate was being used to support legacy infrastructure, adding millions of dollars to annual operating costs. Yet Verizon couldn’t simply get rid of these properties, with their outdated technical equipment and cables, since the remaining network infrastructure still relied on them. And the offices, though underutilized, were often located in highly desirable locations, like Manhattan. Moreover, long-standing commitments made aggregating them and relocating the teams who worked there out of the question. What to do with all this surplus real estate?

A Verizon executive, John Vazquez, had an idea. The company was in the process of adjusting its business model to exploit the growing market for the internet of things. Vazquez saw real estate as a tool to support this strategic change of direction. “For us, it was about taking these assets that were built for one use and transforming them radically to give them another use in a way that could actually add value,” he explains.

Extracting value from idle real-estate assets comes straight from the Airbnb playbook

Extracting value from idle real-estate assets comes straight from the Airbnb playbook. And the conditions that helped Airbnb redefine travel – digitalization, mobility, platform economics and a more open-minded breed of consumer – are likewise making office space another sector ripe for transformation, as evidenced by the plethora of emerging business models dedicated to reimagining the workplace. Empty offices are the equivalent of the spare-room capacity in people’s homes that Airbnb eyed when it shook up the hotel industry. And thanks to a generational shift in how people want to work today – flexibly, not chained to a desk – space has indeed become the new frontier.

Meteoric growth

All around the world, businesses are rethinking workspace – and workspace is becoming big business. It’s no coincidence that Verizon spotted an opportunity in its real-estate challenge when it did. Between 2013 and 2017, the flexible office market was taking off in North America as well as in Western Europe and Asia, representing $26 billion in global revenues, according to the broker Instant Offices.

Given the fast-paced changes of the past decade, many companies find themselves with real estate that’s not only redundant but also too rigid. It’s hard to expand or contract according to market conditions when you’re locked into a 25-year lease. Agility is the name of the game. To innovate faster and more efficiently, companies are trying to imitate the atmosphere of a lean startup, in spaces that foster teamwork and collaboration. To work better and more productively, individuals are demanding workplaces more in tune with their lifestyles. Millennial workers, especially, are demanding this, with one Deloitte survey finding that, given the choice, millennials will prioritize flexible or remote working arrangements that facilitate work/life balance over career progression when evaluating job opportunities.

Speaking at IESE Madrid, Mariano Hernandez (IESE PDG ’18), a senior business development manager for Apple, stressed that just having a strong, established company brand wasn’t enough to attract talent anymore. People are searching for new opportunities and new experiences that enable them to use their talents and grow, wherever they find them. Companies, especially traditional ones, need to adapt themselves – from their organizational models to their workplace cultures to the way they design work – to be more aligned with what motivates modern workers, he said.

All this adds up to a workplace revolution in which boring old real estate is becoming an exciting new form of competitive advantage.

The new players

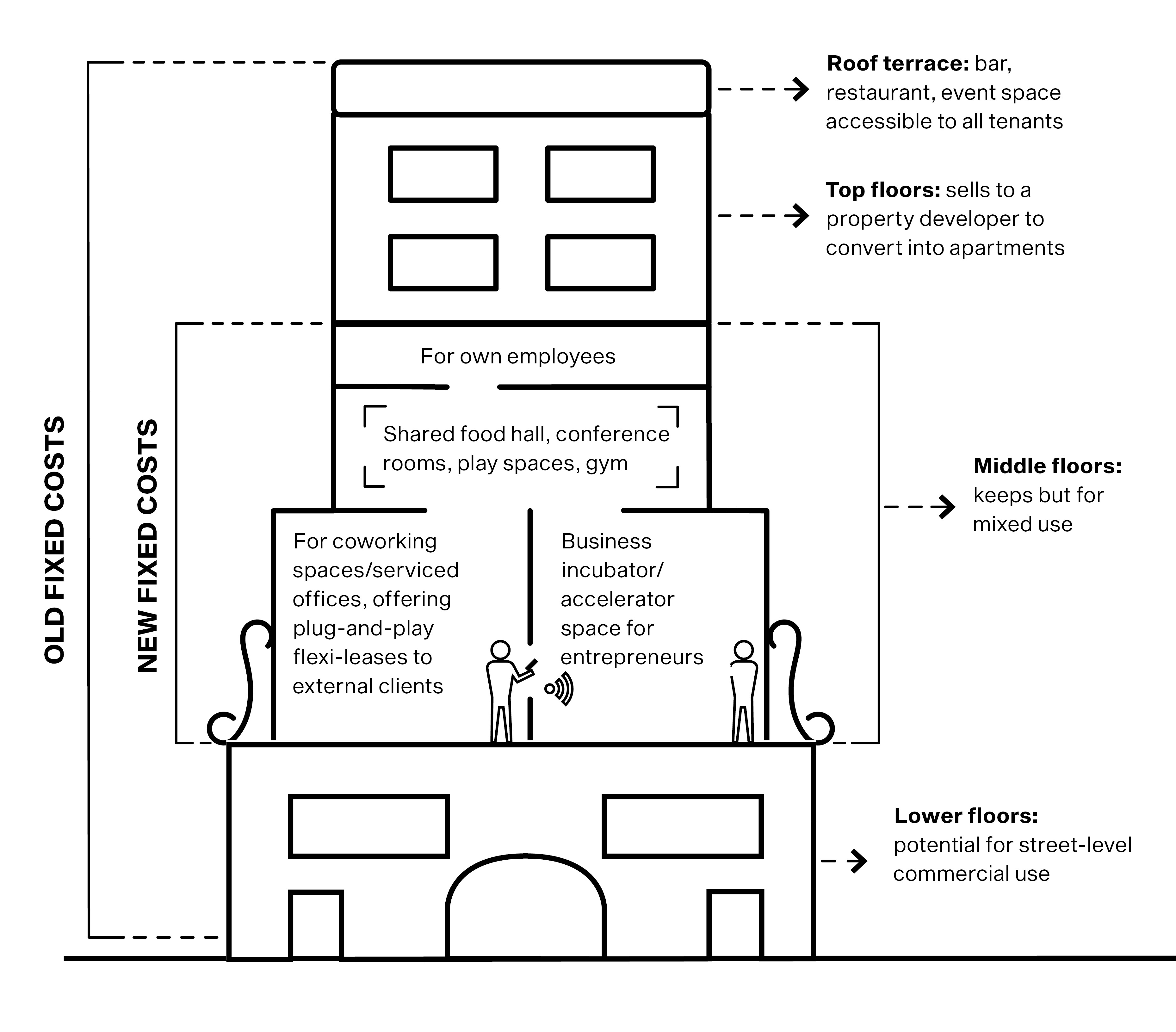

So, what are companies doing? In Verizon’s case, it identified three key areas to address, which will be familiar to many: 1) boost strategic rather than nonstrategic assets; 2) deliver space that fosters productivity and the type of culture demanded by a digitally enabled workforce; and 3) reduce vacancy rates and optimize the utilization of space in strategic assets.

Verizon was sitting on several high-rises in prime locations around New York City. It decided to sell off the top floors to developers, who converted them into apartments. It also sold off the ground floors for retail use. Of the remaining floors, Verizon retained a few for its own employees and equipment; the rest were converted into state-of-the-art coworking spaces that could be offered to different clients, whether freelancers, startups, SMEs or adjacent businesses who needed some spillover space for their expanding operations. In some cases, hotels and medical centers claimed some of these available floors.

Besides opening up new income streams, repurposing these floors generated other benefits: Verizon started to interact with diverse coworking communities under its own roof, learning firsthand from their preferences and utilization patterns, and then applying that knowledge to its own workplace strategies. In other words, experimenting with real-estate-as-a-service became an internal driver of change management for Verizon.

Today’s workers want bright, airy spaces, all supported by the best tech and open 24/7

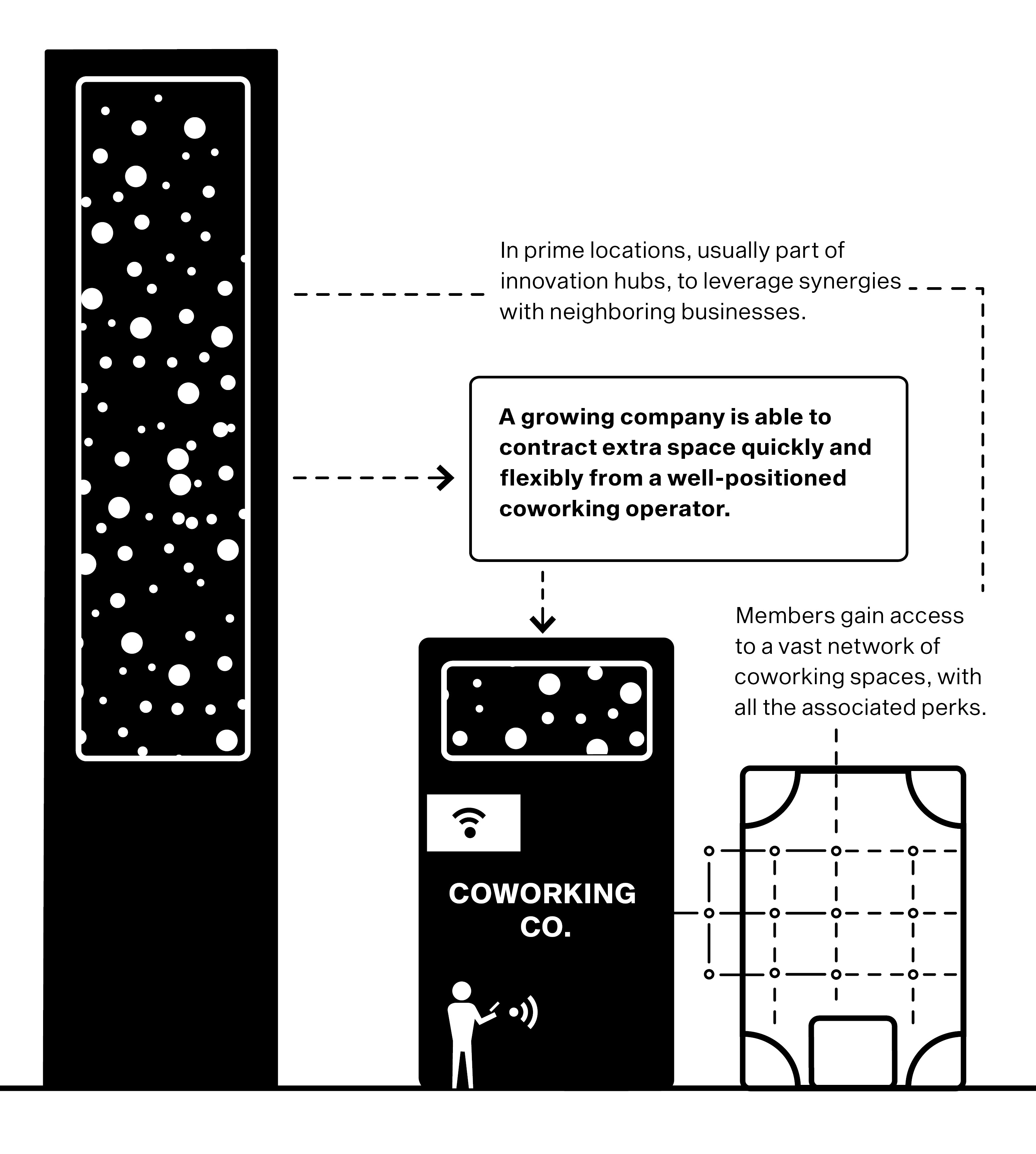

The fully serviced coworking space is another model worth studying. Although there are several big-name shared office operators, such as Regus, which have been around for decades, it’s the startup WeWork that’s grabbing headlines, most recently for its announcement to go public.

Founded in 2010 by two entrepreneurs looking for an eco-friendly coworking space in New York, WeWork is now the fastest-growing lessee of new office space in the United States, if not the world. It specializes in rent arbitrage – leasing or in some cases buying properties, giving them one of its signature makeovers, and then renting the spaces at higher than market prices. A large share of its revenue comes from its membership program: people pay monthly fees for use of WeWork’s global network of desirable facilities, because WeWork isn’t just a desk rental, it’s a lifestyle.

From the beginning, the young founders, who both grew up in communes, instinctively understood what today’s workers want: bright, airy spaces, exercise equipment and playrooms, kitchens stocked with snacks, coffee and beer on tap, conference rooms and common areas where eclectic groups of people can swap ideas and engage in design thinking, all supported by the best tech and open 24/7. They say people come for the office but stay for the culture.

As proof of WeWork’s holistic commitment, in 2019 it rebranded itself as WeCompany to reflect that its real-estate ambitions extend far beyond offices. Its new mission: “to elevate the world’s consciousness.” Now everything can be monetized if prefixed by We, including WeLive (apartments), WeGrow (schools), WeSleep (hotels), WeGive (charitable donations, with WeWork venues doubling as clothing drops), WePark (turning empty parking spots into coworking spaces) and WeWork Go (a Chinese iteration, whereby users pay for space in coffee shops by the minute and get free coffee, rather than the Starbucks model of paying for a coffee and getting space for free).

WeWork’s clients aren’t just entrepreneurial hipsters, either. It serves big-name corporate clients as well, running entire offices for IBM in New York, Airbnb in Berlin and Amazon in Boston, for example.

As the real-estate mantra goes: location is everything. So, when a shared office operator purchases or leases real-estate space – whether a floor or two, or an entire building – it typically scouts prime locations where there is both density and a diverse client base, including some major corporate neighbors. This is because it charges fees per person rather than per square foot or meter, so it needs to make sure there’s a steady supply of clients in the area, in order to guarantee it can continue to cover the costs of providing all the high-quality amenities and services that people have come to expect. As such, shared office operators often position themselves in urban districts that have been specially zoned as tech or startup hubs, à la Silicon Valley, to leverage that symbiosis.

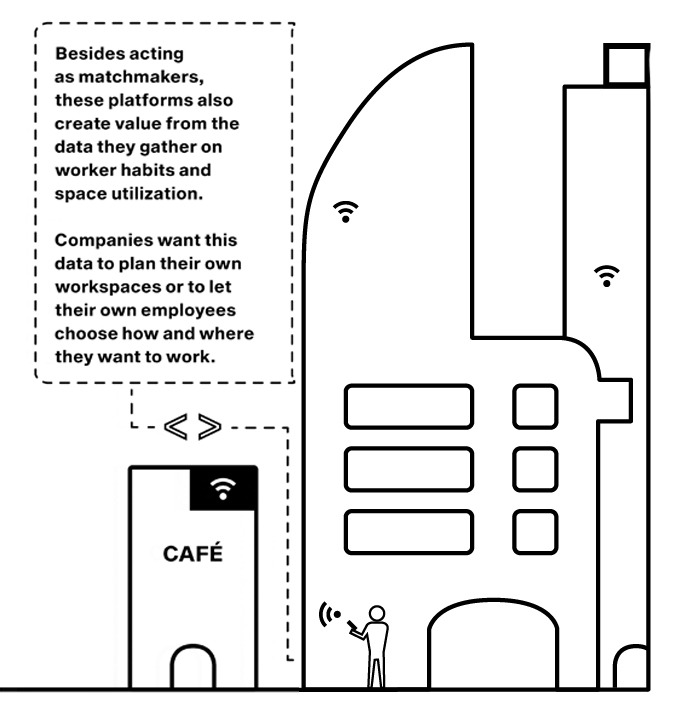

Within this ecosystem is another type of player: the real-estate intermediary. These companies operate in the same space, but unlike the earlier examples, they don’t have any physical real estate of their own; rather, they are online platforms (apps and websites) that link professionals with existing workspaces – be it a desk, a coworking space, a meeting room or a conference facility – aggregating supply and demand, much like Uber or Airbnb does.

Daysk – founded by an IESE EMBA with support from Finaves, IESE’s seed capital fund – is one of a growing number of such companies. It sees the digital nomad or gig worker as part of a global trend and believes demand for alternative places to work will only grow. And the platform is not just aimed at the individual worker looking for the nearest available hot desk; traditional companies are also taking advantage of Daysk’s matchmaking services for their sales people or consultants working on the go, or for helping their employees choose their own work locations. Vitally, Daysk is able to use the analytics it gathers on users to provide corporate clients with rich data on the work habits, consumption patterns and preferred settings of their employees, thereby helping companies tailor their workplace arrangements to real space needs.

Better use of space – and time

The remote or coworking phenomenon has clear benefits, as Daysk founder Julien Palier explains: “If you’re not actually in your office for roughly 50 percent of your working hours because of meetings or travel, but you’re still paying rent or electricity for 100 percent use of the space, then offering remote work policies and reducing the rented office space required for operations bring cost savings while giving employees better control over their own schedules.”

Palier cites a recent study undertaken by the government in his native France to quantify the benefits of flexible HR policies and flexible workspace deployment. Besides the direct benefits for companies – cost savings, less absenteeism, more productivity – workers reported they were able to dedicate the average 73 minutes a day they saved in commute time to other pursuits, leaving them less stressed, with better quality family time and more money in their pockets through the reduction in travel costs, meals and childcare. There were also indirect impacts, such as less fuel use and thereby less pollution. So impressed was the French government by the findings that it earmarked an extra 100 million euros to support labor market changes in this direction.

Workers were able to dedicate the average 73 minutes a day they saved in commute time to other pursuits

That aside, the research in this field is limited. Research on employee/organizational relationships shows that job satisfaction and turnover intentions are linked, to a greater or lesser extent, to employees’ perceived insider status, psychological ownership and identification with the organization for which they work. What happens when those relational ties are loosened? When the place where people work is one brand, when their exchanges and interactions are mediated by another, and when they spend most of their day interacting and socializing with “coworkers” from several different companies or none, do these nomads start to lose touch with their actual employer?

A step forward or a step back?

IBM was a pioneer, as far back as the ’80s, not only in allowing employees to work remotely but in proactively helping them set up office at home. It’s now having second thoughts. Diane Gherson, Chief Human Resources Officer at IBM, recently wrote: “There was a time when we thought all work could be deconstructed and disaggregated and farmed out to freelancers on talent platforms, with just the ‘hub’ work, such as project and client management, being retained by the traditional corporation. The gig economy was gaining momentum as the Uberization of entire industries became more commonplace, and work at home/from anywhere was gaining traction as the global labor market opened and internet and mobile computing became more pervasive. For companies, this was a gift from heaven: labor is purely elastic with demand, and pay is for output, not input. For employees, their needs for benefits were solved by new players … Their need for colleagueship was filled by the emergence of coworking facilities, complete with Starbucks for coffee breaks.”

But, she added, “This moment has passed.”

Instead, she said IBM “embraced agile work at scale,” which involves “co-location,” i.e., teams working together in the same space, albeit a reengineered lab or campus, but the key was in them “coming together” to reap the benefits of engagement and trust – two necessary preconditions for creation to happen, which, she said, was much harder to achieve with a “constant reconfiguration of teams unfamiliar with each other and operating as independent players.”

The ADP Research Institute has a different perspective. It recently completed a global study of worker engagement, based on a survey of more than 19,000 workers in 19 countries. It found that, yes, being fully engaged at work does depend on the extent to which you feel like part of a team. However, it also found that those employees who worked from home or had some side gig – essentially, some other space outside of the normal work environment that gave them flexibility and a greater sense of control over their own schedules and lives – tended to feel even more engaged at work. “Remote workers who feel like they are part of a team are actually more engaged than co-located workers who come to the office and feel that they are part of a team,” asserted Cisco’s Ashley Goodall, one of the study’s co-authors.

By 2020…

50% of the global workforce will be mobile, working flexibly and remotely, across all professional classes and sectors (source: Citrix)

70% of all workers globally work remotely at least once a week and 53% do so at least half the week (source: IWG)

53% of those who work remotely at least once a month said they felt happier and more productive in their roles than those who don’t or can’t work remotely (source: Owl Labs)

New questions

Regarding the real-estate business models themselves, some question their sustainability. Their strength – flexibility – is also their vulnerability. So long as the market keeps growing like it has been, companies can contract additional space from a shared office operator without the sunk cost of real estate, and all parties are happy: the company, the shared office operator and the workers themselves. However, if there’s ever a downturn and the company scales back, apart from any loss of workers and the workspaces/lifestyles they’ve grown accustomed to, the shared office operator – and by implication the building owner and manager, if they have long-term lease obligations – will get stuck holding the bag.

One market analyst, commenting on WeWork’s IPO, pointed out the striking difference between the real-estate operators and other businesses in the sharing economy: “If no one called for an Uber tomorrow, Uber wouldn’t have to pay all those drivers. But if no new tenants show up at WeWork tomorrow, WeWork has hundreds of buildings now, and so that unoccupancy would be an expense.”

IESE professor Carles Vergara, who collaborates on IESE’s annual Real Estate Industry Meetings and who recently published Timing, marketability and location: the new real estate paradigm, notes that real estate “is not mainly about location anymore. Increasingly what counts is its marketability – different uses of the assets, different quality standards, different designs and other factors that affect the assets’ valuation and profitability.” And that requires new skills on the part of investors and managers to analyze and value property in this new context.

And then there are the broader psychological and sociological implications. A European Union research report, Working anytime, anywhere: the effects on the world of work, recognized the positive developments of these new models, particularly in increasing the labor market participation of women caring for children. However, it also acknowledged the disadvantages, including “the tendency to lead to longer working hours, to create an overlap between paid work and personal life (work/home interference) and to result in work intensification.” When taken to extremes, some workers “are more at risk of negative health and well-being outcomes.”

The report made several policy recommendations, including making sure that any novel workplace arrangements adopted by companies “serve the needs and preferences of both workers and employers,” taking extra care to make sure that teleworkers don’t feel “isolated from the rest of the working community,” and safeguarding “the right to disconnect.”

If these business trends tell us anything, it’s that talent becomes more important than ever

IESE professor B. Sebastian Reiche raises another point. These new workplaces “may make your work seem more intrinsically motivating and enjoyable,” he says, “but does this necessarily help you increase meaning? Some will say that being able to decide when, how and where to work in itself helps to make work more meaningful. But to ensure that, you really need to connect with the broader purpose and mission of the organization that you’re working for – and workspace itself may not always help you do that. The rise of new forms of work has profound implications for how workers define their roles and identities. Before we get too carried away by the glamorized portrayal of freedom and flexibility afforded by these new arrangements, we must be mindful of the effects on identity and identification when workers may feel less attached to their physical workspace.”

Vergara underscores that people’s well-being must be at the center of any real-estate strategy. “If these business trends tell us anything, it’s that talent becomes more important than ever. We don’t know exactly what the future holds, but we do know it will be based on the attraction of talent. No matter which real-estate model you pursue to reimagine your workplace, always make sure that it’s flesh-and-blood, not bricks-and-mortar, that matters most.”

More info: IESE professors M. Julia Prats, Carles Vergara and B. Sebastian Reiche have written case studies on Verizon, WeWork and Daysk, respectively.

A new lease on life?

Filling and managing buildings is becoming tricky business

The dilemma faced by Joaquin Castellvi illustrates the challenge that building developers, investors and property management companies have to deal with as part of the new real-estate paradigm.

Castellvi Group has been responsible for several developments, including the Luxa Silver and Luxa Gold buildings, in the 22@ business district of Barcelona. Once the buildings were completed, Castellvi needed to find tenants, which, in his capacity as head of investments and acquisitions for the real-estate management company Stoneweg, he did: Amazon took offices in Luxa Silver.

But with Luxa Gold, it was another story: should he sign a traditional lease with a well-known tech developer, or enter into one of WeWork’s more unconventional arrangements? The former was an attractive, low-risk candidate, while the latter, the hot favorite, was a riskier bet.

If he signed a long-term lease with WeWork, what would happen if the economy dipped and the ancillary business clients on which WeWork depended suddenly dried up? Having Amazon as a neighbor could be a boon, if Amazon expanded and needed WeWork’s space to grow into. But if Amazon didn’t? And what if WeWork didn’t live up to its hype?

Either way, as Fast Company recently noted, developers and landlords realize that, even if they forgo WeWork as a tenant, in order “to remain competitive in real estate … to attract and keep tenants, and boost the value of their properties, they need to be creating similar experiences inside their buildings.”

Today’s tenants expect more from their workspaces.

Coworking companies

These are some of the most popular. Most operate beyond the cities where they were founded.

NYC Alley, District CoWork, Green Desk, Industrious, WeWork

Brussels International Workplace Group, formerly Regus

Slagelse, Denmark SoMeCentral

Berlin Knotel

Vienna Impact Hub

DC Make Offices

Tel Aviv MindSpace

New Delhi Awfis, 91Springboard, Innov8

Sydney Servcorp

Amsterdam Spaces

By 2022…

25,968 coworking spaces worldwide

65% of coworking spaces are occupied by entrepreneurs and new businesses

Top 10 countries for coworking growth per capita

1 Luxembourg

2 Singapore

3 Ireland

4 New Zealand

5 UK

6 Australia

7 Canada

8 USA

9 Hong Kong

10 Bulgaria

Office-finding apps

These are some of the most popular. Most operate beyond the cities where they were founded.

Barcelona Daysk

London Deskcamping

NYC SquareFoot

Toronto Flexday

Vancouver ShareDesk

Utrecht Seats2Meet

Rome MySpot

San Francisco DesksNearMe, LiquidSpace

Blueprint of real estate business models

02Space, the new frontier

New workplace dynamics have given rise to new business models, new players and new market concerns.

Traditional company

Creates new value by repurposing its own idle or underutilized real estate assets

Shared office operator

Creates new value by leasing or buying real estate and transforming it into coworking spaces for all kinds of businesses and individual workers

Real estate platform (apps and websites)

Creates value by connecting workers with available workspaces

Beatriz Arantes: “Be intentional about what you say with your space”

03Space, the new frontier

Beatriz Arantes is Manager of WorkSpace Futures at Steelcase (EMEA), based in Munich. A Brazilian national, she has lived in 12 cities in nine countries, so sees herself as a global citizen. An environmental psychologist by training, she researches the relationship between people and space – “how we inhabit our spaces and what they mean to us.”

Most people think of work as something that happens seated at a desk. But, as Beatriz Arantes points out, “If you reflect on where you’ve had your most productive conversations, where you got your best ideas, a desk with a computer is probably the least of it.”

Arantes manages research at Steelcase, the multinational manufacturer of office environments founded more than a century ago in the United States. Based at Steelcase’s Learning + Innovation Center in Munich, she seeks to connect workers, as human beings, to their organization’s mission, via design. Good design, she says, creates a sense of community and common purpose to get the important work done. Here she discusses emerging trends in workspaces and how organizations can meet the future.

What’s happening in workspace design?

I see a huge paradigm shift, one that’s not fully apparent to the general public yet. We’re moving away from designing workspaces for traditional departments or functions like HR, engineering and marketing. Instead, we’re moving toward designing for project work, involving team members from many areas.

Today, a new kind of teamwork is crucial for organizations to respond quickly to market changes and customer needs. Innovation requires a multidisciplinary approach. That’s hard because people have been trained to think in one discipline – to become experts. But the task of creative collaboration for innovation is to break down what people know from their disciplines, to break down their mental models, and negotiate. Our research finds more of that work gets done when people are sitting side by side, tackling problems together.

And yet designing for teams also means supporting individual work within the team. A good workplace will provide a mix of contexts to work individually and socially, digitally as well as analog. If a workspace is helping us to be more effective at what we do, we will come back to it, and that’s the key.

How do you design effective workspaces?

It doesn’t begin with the space. It begins with defining the organization’s vision for the future. We ask the leadership, “Where does your organization need to be in five to 10 years, and how do you plan on getting there?”

Together, we paint a picture of the new culture, processes and technologies that need to be in place. And through workshops, the employees help us understand how they work and how they see themselves in this evolving organization. We also consider other stakeholders, such as visiting employees, customers and suppliers, who are coming into the space. Everyone should feel welcome.

Any design tips? There seems to be some pushback against open-plan offices.

“Open space” goes wrong when it’s used thoughtlessly to optimize real estate. We’ve seen many floorplans where it’s row after row after row of desks. This is the epitome of telling someone that they’re just a number in the organization.

A basic tip for designing a good experience without walls is to create neighborhoods. Don’t make it a sea of desks. Smaller communities help people get to know each other and feel like they’re responsible for their space. That way, they can organize themselves and establish a common etiquette to manage things like noise. You can also do simple things like providing phone booths for making calls.

“In open-space offices, don’t make it a sea of desks. Create neighborhoods or smaller communities”

Really, it’s about humanizing the space. What elements are you bringing in to make people feel comfortable, not just physically but cognitively and emotionally?

How do you design for authenticity?

It’s about aligning the values of the organization with the message that the space is conveying – because spaces do convey messages: they tell us what – or who – matters in the organization; they provide clues to acceptable behavior. That’s why you have to be intentional about what you’re saying with your spaces, because employees are going to read into it, even if that message was not intended.

For example, I recall a company that had a regular coffee machine for employees and a special espresso machine for clients. But the employees who attended to clients felt entitled to make themselves espressos while the other employees didn’t. This created a division. Eventually the policy moved to espresso for everyone, so that everyone felt valued.

For global companies, you can’t just copy-and-paste what works in one location to another. Human beings want to understand the why of the particular space they’re in. If you want people to be engaged at work, you have to make sure their space has a community in which they feel they belong. This goes back to knowing what your organization is trying to achieve, what behaviors it wants to promote, and then creating a space that makes sense to those people working in it.

How is workplace design tapping into the natural world?

We’re studying biophilia, which is taking the feel-good qualities of natural environments and translating them into interior environments. A key element is sensorial richness: you feel well when you can observe, as in nature, harmonious complexity. And you can bring that into the office, not just literally with plants and wood, but also by incorporating diverse materials, textures and textiles that hint at the patterns and colors we see in nature. Boring, repetitive environments lead to bored, uninspired minds. Neuroscience research confirms that creativity is a non-linear process involving different types of brain activity. Spaces should reflect that diversity.

6 dimensions of well-being

How well does the design of your physical work environment foster these six dimensions that Steelcase has found impact personal well-being?

Mindfulness Does it help you be fully present?

Authenticity Does the space welcome sincerity and self-expression?

Belonging Are there places to connect and bond with others?

Meaning Is the purpose of your work and its impact on the world visible?

Optimism Does the space empower you to get your work done?

Vitality Does it support a healthy and balanced lifestyle?

Daniele Di Fausto: “We can organize real estate according to the people”

04Space, the new frontier

Daniele Di Fausto (IESE AMP ’19) was appointed CEO of eFM when he was just 35 – “a courageous decision unusual for the real estate sector,” he says, representative of “management’s transparency and lack of hierarchies,” which is needed to revitalize real estate for the next generation.

Like many companies, eFM, an Italian engineering firm focused on real estate, found its traditional business being upended by digitalization. While it had been using information technology, it was mainly in the form of showing corporate clients how to reduce costs. “But with the internet of things, we started to understand we could do more,” says CEO Daniele Di Fausto. “Space could become a service. This is the trend with which we want to grow the company.” Here he explains what they did and where they might go next.

How did you acquire new skills?

We used ourselves as an experiment, turning our own office into a connected environment. Using sensors and cameras, we measured the occupancy of our space for each desk, each person and each interaction. Everything – door access, meeting rooms, attendance, maintenance – was handled electronically. In two years, we learned how to create an environment of open innovation.

But that’s inside the building, whereas your mission talks about using tech to release work from time and space constraints.

For that, one of our guys did a separate study. He took 4,200 bars in Rome, analyzed their saturation rates using Google Analytics, and found 80% of the time the bar was busy between 8:45 and 9:30 a.m. and 12:30 and 2:30 p.m. The rest of the time, there was no one. I thought, “This is interesting,” because in the future, work won’t be concentrated in offices in a single building anymore.

Now, put this together with our measurement of desk occupancy. For most companies, a desk isn’t occupied more than 50% of the time. So, not only can we tell companies how they can achieve savings by reducing their space based on average occupancy rates, we can do something even more interesting: we can advise companies on how they can invest part of that savings in improving the engagement of their workforce by not having a centralized office building, and then providing the data on all the alternative places in the city where their people can go and work instead.

How did that lead you to create your spin-off company, MySpot?

Once we had this concept of connecting places in the city, I issued an open invitation to anyone in our company who was interested in exploring this idea further. Within two hours, I had over 50 employees saying they wanted to work on this idea. I said to the ones who were really pushing the idea, “You’re in charge of a startup. I’ll give you $70,000 and five months to develop a prototype. And you need to work with a business accelerator outside the company. If you manage to get enough transactions from freelance workers, then we’ll know if the idea really is good.”

After five months, they came back with some unexpected findings. They’d started with freelancers, but what they found was that employees of traditional companies were most interested, because they were able to choose workspaces near home or near their kids’ kindergarten. Employees said, “If I have to go out to a meeting in another company, why do I have to go back to my company to work, before going back home? I could just work from another place near the other company or near my house.”

Based on that, we launched MySpot, a platform matching professionals with available spaces in Rome and Milan. Last year, Gartner named MySpot one of the five coolest digital workplace vendors.

Where do you see this going next?

Retail. We think shopping centers, which have already undergone digital transformation, will be further transformed into “experience centers” where people will meet to exchange different experiences. Say I want to learn about blockchain or design thinking: each place would have its own little community of people interested in that subject, and you could find them via the platform and meet up. Work will become more distributed. It also means spaces will become more hybrid, each with its own special character. So, a café or shop would also become a community organized around a certain specialism. With technology, you can orchestrate this kind of thing and transform real estate from a destination into an entirely new economy.

We envisage this happening at the city level, too. For example, during the 2015 Milan Expo, we came up with the idea of using smart technology in the common areas to understand the connections, exchanges and interactions of people in those places. Our “smart city” operating system was selected among the projects that will form part of MIND, the Milan Innovation District. The ground floors of the buildings in the district will be “common ground,” open to all citizens. In other words, we’ll use it as a testing ground or living lab to see how smart spaces can foster more creative connections and engagement between people, leading to more innovation and value creation, at urban scale.

What else are you experimenting with?

We have the digitalization of real estate, but now we’re exploring the digitalization of people, with a matching platform that creates an experience. Take my smartwatch. From the moment I enter my building, it can detect my heart rate, indicating if I am stressed or relaxed, and I can decide whether to share this information with other people. Suppose, as a team, we agree that an equal distribution of speaking time in a meeting is important to us. With technology, we’re able to measure that. Suppose we don’t just track the number of words spoken but the tone. We can get feedback on the quality of the interaction. This information is stored in my “digital diary,” which tells me, “Daniele, the last time you had a meeting in this room, you got angry. I suggest you have a separate discussion with this guy beforehand.” This means we can organize real estate according to the people, not just in terms of providing the right furniture, but even having the possibility of selecting the right people to attend the meeting to make this experience successful.

Doesn’t this raise privacy concerns?

This is absolutely important, especially in Europe, with General Data Protection Regulation. We believe in anonymized data. The information would be held in blockchain across a distributed network. Crucially, the user must have complete control over whether they want to share their personal data or not, and how much. For example, you might want to share just this one piece of information, with this one person, in this one-hour meeting, after which it would disappear.

I have a millennial mind, which means I’m willing to share information with others if: (1) it may be helpful to me personally, to have a better awareness of myself; (2) it may be helpful for others, for us to have a better awareness of each other; and (3) it may be helpful to the community, for us to improve things as a company or team. This goes to the concept of “digital common goods.” I share information, not to receive an advertisement, but to create networks of positive things – to improve collaborations, increase human capital and build trust. Any platform we develop must be compliant with these principles.

“Look at us: we started as an engineering company and now we’re putting HR and technology together to create connections between people and real estate”

What kind of organizational culture is needed for this?

Like nature, an organization is a complex system. And just like nature doesn’t have a boss yet still works, organizations work best if there’s no boss who controls you but instead empowers self-managing teams. Let people try new things. If someone has an idea, be ready to test it, and if it works, there’s value. Look at us: we started as an engineering company and now we’re putting HR and technology together to create connections between people and real estate. In the end, we’ve transformed real estate from a cost-reduction approach to a value approach, because if the real estate is good, people will be happy; if people are happy, they’ll be more productive; if more productive, they’ll generate new ideas, more innovation and better results.

From CAPEX to UX

05Space, the new frontier

Today a building is not just a building. “Real estate has moved from bricks to people,” says Anna Esteban, Spanish director of CBRE, the global real-estate services company. By this she means what used to be a B2B capital expenditure (CAPEX) is now about landlords creating bespoke user experiences (UX) that please commercial tenants from the minute they walk through the door. “Space used to be seen as a cost, and while occupiers will always be cost-sensitive, increasingly they see space not just as a container of activity but as a vital part of the value chain – strengthening brand positioning, supporting corporate values, and helping to attract and retain talent. And for that they’re willing to pay premium.”

Here Esteban highlights the four key levers by which companies are using real estate to enhance their appeal.

How can we achieve balanced lives?

06Space, the new frontier

As the boundaries between our personal and professional lives continue to blur, what can we do to achieve better balance? Creating workplaces that allow people to balance their lives is good for a variety of reasons. It’s responding to reality: people have family responsibilities, whether caring for young children or elderly parents, and giving them the flexibility they need to carry out those responsibilities helps them feel more in control, more positive and more energized.

Research shows this translates into greater commitment, engagement and motivation at work. It’s also shown to attract and retain talent. Yet, as vital as balance is for today’s workers, achieving it has gotten much harder in our constantly connected, globalized societies where we work across multiple time zones and everyone expects an instant response. For all of technology’s advantages, it is also one of the chief culprits in keeping us from fully engaging with our non-work pursuits and responsibilities as much as we’d like or need.

While we can’t simply eliminate all demands and pressures, we can at least foster organizational cultures that favor work-life balance.

Balance starts at the top, trickling down to employees. Given this, how well do your company’s leaders demonstrate their own commitment to work-life balance? Are they as enthusiastic about personal or family engagements as they are about work ones? The supervisor’s level of non-work engagement has an important “crossover” effect: as employees perceive it, they come to view balance in a positive light and seek to emulate those behaviors for themselves. Leaders who are able to disconnect outside of work make it easier for others to do so, too.

This is one of the findings of recent research I did with colleagues on how well-being in work and home domains trickles down from supervisors to subordinates. While other studies have explored this dynamic at the peer-to-peer level, we found that supervisors played a special role in making it cascade throughout the organization. Those supervisors who engaged more at work saw how their subordinates performed better at work; likewise, those supervisors who engaged more at home had subordinates who enjoyed more satisfaction at home. This “crossover” effect is distinct from “spillover,” whereby the actions in one domain (work) might have unintended consequences on the other (home).

It’s worth remembering that this effect can be for good or ill. When supervisors don’t have good work-life balance themselves, their subordinates will also perceive this and presume that home engagements are not organizational priorities. Supervisor behavior regarding family balance might have a much bigger impact than any written policy.

That’s why leaders should strive to set a good example. Yet, as important as role-modeling is, it helps if your organization already has the right policies in place, so that your behavior is validating and reinforcing, rather than fighting against, your corporate culture. In this, HR plays a key role. Actions include:

- running workshops with supervisors to train, educate and increase awareness of family-supportive behavior.

- assessing employees’ needs for being able to balance their work requirements with their personal circumstances.

- providing self-assessment tools for employees to monitor their own performance in work and home domains.

- using behavioral modeling techniques, such as role-playing, to practice the behaviors you seek.

Another tool is to allow “idiosyncratic deals” or “i-deals,” which are personalized arrangements specific to the work-life needs and preferences of the individual employee. I-deals generally boost employee satisfaction and reduce turnover intentions. Again, supervisors who enjoy i-deals are more likely to extend them to their teams, and subordinates are more likely to take them up if they see their supervisors using them positively.

Remember, as a leader, you must have work-life balance not only for your own good but for the good of those you lead and the organization as a whole.

Mireia Las Heras is an associate professor of Managing People in Organizations and research director of the International Center for Work and Family (ICWF) at IESE.