Countdown to 2030

01Countdown to 2030

Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals. Are you ready?

In August 2019, the Business Roundtable representing top U.S. companies released a headline-grabbing Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation signed by 181 CEOs. In a significant about-face from previous statements issued since 1997, the signatories affirmed that a corporation exists to create value for all stakeholders, not just shareholders, and they committed to leading their companies based on this logic from now on. Investing in people through fair pay, education and training; dealing fairly and ethically with suppliers; protecting the environment; embracing sustainable business practices: these were to be companies’ animating purpose going forward.

The announcement got a mixed reception. At the time, teen climate activist Greta Thunberg was crossing the Atlantic in a zero-emissions, solar-powered boat to deliver a stinging rebuke to leaders for their lack of action on environmental sustainability. “People are suffering. People are dying. Entire ecosystems are collapsing,” she told the United Nations Climate Action Summit upon her arrival in New York. “We are in the beginning of a mass extinction. And all you can talk about is money and fairytales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!”

We need to see business leaders really starting to put their money where their mouth is

Perhaps sensing the tide of public opinion was turning against them, the CEOs appeared to be scrambling to position themselves in the “woke” camp, and critics dismissed their statement as PR. Others were less cynical, welcoming their statement with cautious optimism. Everyone agreed that for the statement to amount to more than nice words, we’d need to see business leaders really starting to put their money where their mouth is.

Time is of the essence. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is 10 years away and there are legitimate fears that it won’t come anywhere near to being met unless the business community wakes up and begins to act with more urgency. Certainly, the countdown has begun.

Growing pressure

How did we get here? Back in the 1990s, the United Nations initiated a series of conferences that brought member states together to define the most urgent priorities for the 21st century. This led to the development of eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which all member states were meant to achieve by 2015. The MDGs were aimed at lifting up developing countries, doing things like eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, reducing infant mortality rates and improving access to education. Almost from the start, the U.N. recognized that this would require a concerted effort by everyone — not just governments but companies too — so it established the Global Compact in 2000 specifically to enlist the help of the business community in advancing the goals. By 2004, the U.N. Global Compact had agreed on a list of Ten Principles, grouped under four broad headings: human rights, labor, the environment and anti-corruption (see the Lise Kingo interview for more on this). These were meant to set a minimum standard for companies’ actions around the world. By 2015, admirable progress on the MDGs had been made and the Ten Principles were becoming broadly accepted. To keep this momentum going, another 15-year plan was launched, the current Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These consisted of 17 goals, along with 230-plus allied indicators, broader in scope but similarly trying to get public and private stakeholders worldwide to work together to build “an inclusive, sustainable and resilient future for people and the planet,” in the words of the U.N.

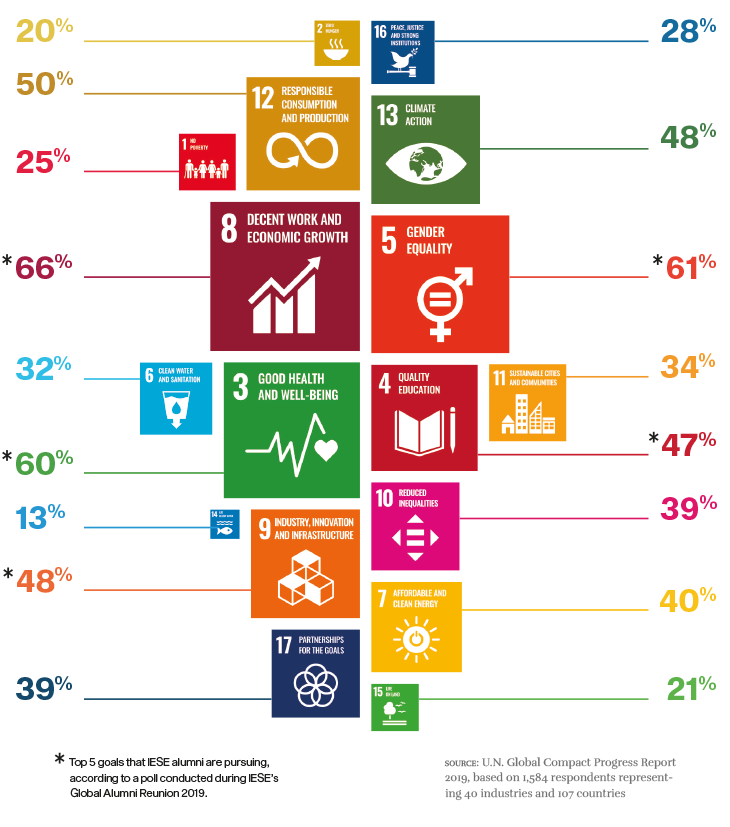

Which goal is your company taking action on?

Sized to show which goals companies have prioritized to date.

Positive impact achieved so far

Companies reporting significant or somewhat positive impact on the goal to date.

IESE Dean Franz Heukamp believes the shift toward sustainability is a positive development and the SDGs represent one of the most practical frameworks for thinking about the issue. “They’re resonating with more businesses, investors and people in society,” he notes.

More and more firms are embracing the agenda. For example, Inditex — the parent company of Zara, whose fast-fashion business model is viewed by some as inherently unsustainable — recently announced that all its garments would be made from sustainable fabrics by 2025 and that the energy its distribution centers, offices and stores consumed would shift to renewables. And Schneider Electric, which sponsors a Chair of Sustainability and Business Strategy at IESE, has committed to become carbon neutral by 2025 and achieve net-zero operational emissions by 2030.

“Sustainability issues are an increasingly visible part of the business landscape,” says Mike Rosenberg, who has been studying and teaching sustainability for more than 20 years. “There has been a clear spike in awareness and public commitment, and I think we might finally be seeing a tipping point in the response of business.”

Pressure is building from multiple sources. “Increasingly consumers are asking more from brands, with millennials, in particular, saving their dollars for those with responsible business practices,” says Rosenberg.

In his classes at IESE, Rosenberg gets diverse groups of students to weigh up the SDGs and try to figure out which ones they would implement in their part of the planet, and why. “They study the link between business strategy and sustainability, and build wikis on their chosen topics. One of my favorite ideas that they came up with was to use satellite technology to measure the achievement of the SDGs using direct measurement of the planet from outer space.”

Some of these visionary students go on to become socially engaged employees and business leaders, trained to think strategically about sustainability, and they change their companies from within. Rosenberg mentions a former MBA student who went on to head up Responsible Retailing for a major multinational — a role that didn’t exist before but was now considered a key pillar of the company’s growth strategy. “Some members of this generation are combining their passion and energy for sustainability with business fundamentals like never before,” he says. “To stay competitive in the labor market, companies have to embrace these values.” He cites recent pledges by Silicon Valley tech firms to become carbon neutral as evidence of them recognizing they need to boost their brand proposition among 20- and 30-year-olds.

Your company must have its purpose clear. This purpose needs to act as the lodestar for the organization, lending legitimacy to all its activities

The pressure is also coming from investors. Rosenberg’s Strategy Department colleague, Fabrizio Ferraro, has been studying responsible investing for over a decade. He points to the staggering growth of a sector that is going mainstream: “There are now more than 2,000 signatories to the U.N.-sponsored Principles for Responsible Investment, with almost $90 trillion in assets under management. This form of investing integrates Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) criteria and increasingly uses the SDGs as its guide. These shareholders, through their investment decisions and engagement activities, are forcing corporations to confront ESG issues directly at the board level. And their efforts are starting to pay off. The Climate Action 100+ coalition of investors, for instance, recently convinced Royal Dutch Shell to set stricter carbon-output targets and commit to halve its net carbon footprint by 2050.”

Purposeful leadership

So how do we get from where we are now to where we’d like to be? For Antonio Argandoña, the SDGs provide “a useful framework to help us move forward, giving us reference points to check our progress, so we don’t find ourselves in the position a year from now of having to start all over again.”

To stay on track, your company first needs to have its purpose clear. “One of the most effective means of building strong relationships with stakeholders is to have a relevant purpose shared by all members of your organization and which gives meaning to their daily work,” says Nuria Chinchilla. This assumes that leaders have dedicated time and resources at three levels: 1) to reflect deeply on what their purpose is; 2) to communicate it well, both to employees and to other leaders; and 3) to adapt their management systems accordingly, with good feedback mechanisms and measurement instruments in place. This purpose needs to act as the lodestar for the organization, lending legitimacy to all its activities.

For too long, companies haven’t had a clearly defined stance on sustainability. Their purpose was to make as much money as possible, without sparing much, if any, thought for the social consequences. As Rosenberg remarks in his book, Strategy and Sustainability, for decades many companies simply refused to accept that a problem existed, or if they were aware, they chose to cover it up, employing crisis managers and PR professionals to put the best possible spin on their activities rather than engaging in any serious reflection or redesign of their products, services or operations. But those represent reactive responses, when what is urgently needed are more proactive strategies — in particular, a deep, broad engagement with these issues by senior management, if not a full-scale transformation or renewal of the firm itself, one that treats the SDGs not as boxes to tick but as opportunities for reinvention.

Sustainability = better performance

The University of Oxford and Arabesque Asset Management analyzed 200 academic studies to determine if sustainability business practices and economic performance were linked…

90% of the studies showed that sound sustainability standards lowered the cost of capital.

80% of the studies showed that stock price performance was positively influenced by good sustainability practices.

88% of the studies showed that Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) practices resulted in better operational performance.

ESG & financial performance

In a Boston Consulting Group study of 5 industries (consumer packaged goods, biopharmaceuticals, oil and gas, retail and business banking, and technology), the top performers in ESG topics (such as ensuring a responsible environmental footprint or promoting equal opportunity) reported…

Up to 19% higher market valuation premiums

Higher margins by up to 12.4 percentage points

There’s no one-size-fits-all approach, Rosenberg insists. Each company needs to look at its own situation in terms of its customers, employees, shareholders and relationships with governments and interest groups to determine what the right level of response might be. This could range from making sure that your company is fully compliant — what he calls “taking the low road” — to realigning your business purpose and then proudly “showing and telling” the world about your achievements with respect to the goals.

But make sure “show and tell” is not just for show. “When sustainability is intertwined with the strategy of an organization, then we should expect to see that reflected, not just in the annual report, but in everything,” adds Joan Fontrodona, holder of the CaixaBank Chair of Corporate Social Responsibility and director of the Center for Business in Society. So, if we conceive of a company as a community of people, serving other people, in a society made up of people, then all other considerations — capital, facilities, technology and legal realities — become subordinate to that, and the story we “show and tell” about our company’s progress will begin to look rather different.

Using the right indicators and metrics appropriate to your goal is important, but even more so if you decide to adopt the strategic option that Rosenberg refers to as “pay for principle.” This is where your company may be willing to sacrifice some financial performance for the sake of a compelling, socially responsible agenda. In some cases, shareholders might support a company doing things that are difficult or even impossible to justify purely from a bottom-line perspective, but this still entails being able to put a number on it, for the sake of transparency.

Lead by example, going above and beyond baseline compliance. Always act with integrity and a social commitment

This necessitates a specific management style, as Fontrodona describes. Managers must courageously lead by example, going above and beyond baseline compliance. Their leadership will be characterized by integrity (always behaving in a responsible manner with stakeholders) as well as a social commitment (getting involved in activities that improve society as a whole) and in particular a commitment to the local community in which the business is based and has influence.

Leaders must also cultivate a hybrid mindset, able to blend different logics. Ferraro sees this job of orchestrating the pluralistic demands of multiple stakeholders as increasingly part of the CEO agenda. He highlights the unlikely collaboration between Dow Chemical and The Nature Conservancy. Not that long ago, a partnership between a chemical company, seen as polluting the environment, and an NGO, responsible for protecting it, would have been unthinkable. But as he notes, “Rather than pitting conservation goals against financial ones (as would have been done in the past), the chemical giant and the environmental NGO collaborated on finding operational solutions that jointly addressed business concerns and the protection of the natural environment.” In short, CEOs are learning how to reconcile the pursuit of sustainability goals with profitability, and to work in partnership even with strange bedfellows.

Finding common ground

Both Ferraro and Rosenberg have long argued that part of the reason why the private sector has been a bit slow to pick up and run with the sustainability agenda is that the arguments haven’t always been convincingly framed in business terms. And when the subject is raised, the language has tended to be combative rather than constructive in tone. To make headway on the goals, companies and their shareholders and investors need to change the way they talk to each other and find common ground.

In his research on shareholder engagement, Ferraro studied the early history of engagement on climate change, specifically how the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility (ICCR) — a coalition of institutional investors who advocate for ESG concerns — engaged with U.S. carmakers on the issue of global warming in the 1990s. With Ford, one of the keys to successful engagement was the active reframing of the issue from climate policy (which could be dismissed as a matter for public policymakers, not a business concern) toward climate risk, a concept more likely to resonate with executives. Risk is something that demands managerial attention. Through this, Ford became one of the early carmakers to break ties with the climate-change-denying lobby, launching a first-of-its-kind climate risk report and focusing on making more environmentally friendly cars.

As such, it’s worth reflecting on the way we talk about the SDGs in our own companies. It’s not just semantics: the language we use, and our strategic use of dialogue vs. in-your-face activism, genuinely does influence managerial receptivity, attention and adoption. Naming-and-shaming activism can lead to boardroom standoffs and showdowns, whereas making a persuasive business case may be more effective at producing the real, lasting social change that sustainability advocates seek.

Righteous indignation

That said, there are other key factors that could move the SDGs up the corporate agenda: executives’ capacity to tap moral convictions and their susceptibility to “system justification.” According to research by Sebastian Hafenbrädl, those who see the world as just and fair, who believe that everyone gets what they deserve and deserve what they get, tend to be numb to social and environmental problems. So, no matter how sound the business case may be for supporting the SDGs, if that business case is predicated on a “fair market” ideology, then its effectiveness as a driver of change is neutralized.

“Framing everything as a business problem isn’t enough. To make authentic improvements in what are essentially moral and ethical problems, they need to be recognized as such,” says Hafenbrädl. “Most people are quite capable of moral reasoning in their personal lives. Our research suggests that if executives were able to access their moral emotions and intuitions and use their capacity for moral reasoning at work, they would engage more strongly, and more substantially, in socially responsible activities than if they just analyzed every decision in terms of the business case. And this applies even for executives who strongly believe in the business case for corporate social responsibility.”

It’s worth reflecting on the way we talk about the SDGs in our own companies. Framing everything as a business problem isn’t enough

The late Ray Anderson, founder of the carpet maker Interface, is a case in point. In the documentary The Corporation, he recounts his personal journey from apathetic executive to champion of sustainable manufacturing, owing to a moral awakening. “For 21 years I never gave a thought to what we were taking from the earth or doing to the earth in the making of our products.” It was when he was asked to present his vision to a task force on the environmental impact of their operations that he began to read up on the matter, and his conscience was pricked. “I was amazed to learn just how much stuff the earth has to produce through our extraction process to produce a dollar of revenue for our company. When I learned, I was flabbergasted.” It was biologist E.O. Wilson’s phrase “the death of birth,” referring to species extinction, that Anderson said felt like the “point of a spear into my chest” which was “an epiphanal experience — a total change of mindset for myself and a change of paradigm (for my business).”

Later, he addressed civic and business leaders as “fellow plunderers.” In a provocative speech, he said: “There is not an industrial company on earth, not an institution of any kind, that is sustainable. I stand convicted. But not by our civilization’s definition. By our civilization’s definition, I’m a captain of industry, a kind of modern-day hero. But really, the first Industrial Revolution was flawed, it is not working, it is unsustainable, it is the mistake. And we must move on to another, better industrial revolution and get it right this time.” He painted a picture of an organization of people committed to a purpose of doing no harm.

Today, Interface is well on track to meet the bold Mission Zero vision that Anderson set in motion before his death in 2011, to fully eliminate the negative impacts of its manufacturing processes by 2020.

Transforming society

As we head toward 2030, companies have an important window of opportunity before them. Over the next decade, it will be up to you and your company’s leaders to decide the role you want to play in this ambitious effort.

“At IESE, we’ve been talking about the purpose of the company and its social responsibilities since our school was founded in 1958,” says Antonio Argandoña. “While the Business Roundtable statement may not, in itself, be revolutionary, it can help spark a revolution. How? If all those signatory companies truly began to behave as their declaration says — upholding the needs of their customers, employees, suppliers and local community stakeholders in addition to their shareholders — then that will foster a new culture and new habits in terms of the way business is done. That is how virtue is developed. And the more that people behave with virtue, the more that others follow their example, giving rise to even more virtue. In this way, companies can become moral transformers of society. May it be so.”

As you reflect on your own progress toward 2030, let these final words from Greta Thunberg echo in your ears: “How dare you pretend that this can be solved with business-as-usual. The eyes of all future generations are upon you. We will not let you get away with this. Right here, right now is where we draw the line. The world is waking up. And change is coming, whether you like it or not.”

Note: IESE is a signatory of the Principles for Responsible Management Education and the U.N. Global Compact, dedicated to supporting the Sustainable Development Goals through management education, research and thought leadership globally. IESE runs various initiatives to promote social responsibility and sustainable development in business, including its research centers and chairs (notably the Center for Business in Society, the Fuel Freedom Chair for Energy and Social Development, and the Schneider Electric Sustainability and Business Strategy Chair) as well as regularly organizing Energy Prospectives seminars with the Naturgy Foundation.

A great transformer of society

The Grand Chancellor of the University of Navarra, Monsignor Fernando Ocáriz, presents this positive vision of the company.

Companies are, above all, communities of people. And those people show up to work every day for the usual reasons: to earn a living and support their families; to acquire new skills and knowledge; to enjoy career opportunities and experience personal satisfaction.

But people also seek and need relationships with others, since we are inherently social beings. Companies should be an expression of that, too, meeting not just people’s material needs but our spiritual ones as well. Through work we make friends and help others; we feel useful and contribute to a common project. And in the process of serving others, we get to know ourselves better, grow and become more complete human beings, for the betterment of society as a whole.

Satisfying the needs of other people is an obvious part of every company’s mission, namely through its provision of goods and services. But satisfying the social dimension is no less important. Companies need a purpose or goal that nourishes people and transforms them, as the enterprise interacts with society and endeavors to generate prosperity for all.

For this, we are prepared to devote our time, effort, attention, knowledge and enthusiasm, beyond the salary or benefits in the employment contract. Indeed, the greatest opportunity a company can provide is for each and every one of us to transform ourselves.

Too utopian? Certainly, our daily news confronts us with the negatives: fraud, layoffs and market manipulations; work that is inhumane and incompatible with family needs; technology that worsens inequality and threatens people’s future prospects.

Yet such realities should spur us to make an urgent course correction away from the lopsided focus on economic dimensions, efficiency and market share, and put our focus back on people. Ultimately, transforming the world comes down to how we transform the people inside our companies.

One word: plastics

02Countdown to 2030

“I want to say one word to you, just one word: plastics.” The businessman who uttered this immortal line in the classic movie The Graduate turns out to have been right in predicting the growth area of the future, as global plastic production since 1967 has grown exponentially. However, his other prediction that “There’s a great future in plastics” is looking less certain these days – a point that today’s generation of graduates would do well to contemplate. When it comes to the business of plastics, to quote the film again: “Think about it. Will you think about it?”

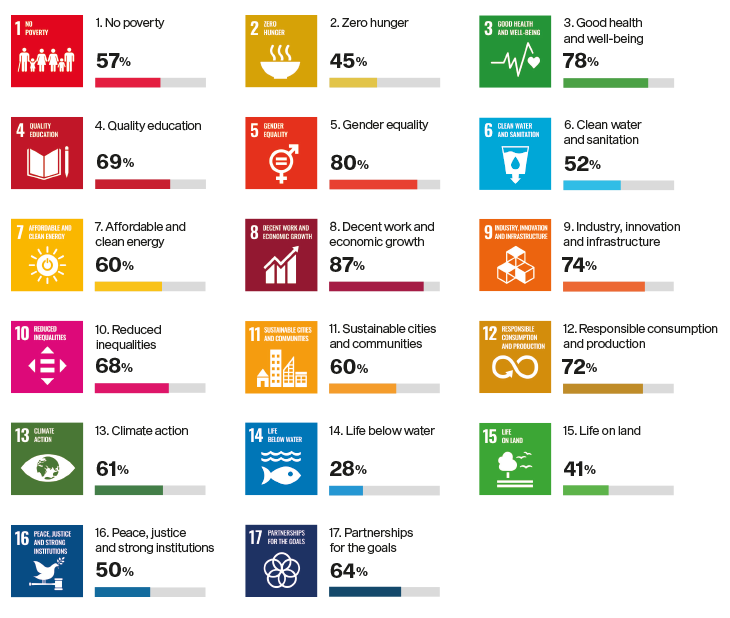

Source of stats below: Eurobarometer, Factsheet of the European Commission, and the DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on the reduction of the impact of certain plastic products on the environment (2019).

The problem

The EU initiative

Already a world leader on data protection, the EU adopted the Single-Use Plastics Directive in May 2019, with rolling deadlines of between 2 and 5 years for member states to implement its rules to:

The main offenders

Business action plan

Know how it affects your industry

If you’re a producer of single-use plastics, know where you stand. Some plastic products, such as cotton swabs, straws, plates and cutlery, will be banned outright.

Spot opportunities

Some plastics will have to be phased out, but others may be more in demand. Additives that change certain plastic properties could be a business opportunity. New recycling technologies will also be necessary.

See the bright side

Green companies are growing, and European regulation is likely to make the region a hotspot for sustainable product development and – as with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – a reference point for the world.

Download One word: plastics

Lise Kingo: “It’s time for everyone to step up”

03Countdown to 2030

Lise Kingo is CEO and Executive Director of the United Nations Global Compact, which urges companies to adopt a principles-based approach to doing business in support of achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

Sustainability: we talk a lot about it but what is actually being done? Lise Kingo left her private sector job at Novo Nordisk, where she championed the cause, to help lead the charge with the United Nations. Here she discusses where the U.N.’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) stand today and what more companies can do to put them into practice.

Is the world on track to meet the goals?

There has been good progress but not the kind needed to meet the goals by 2030. The two biggest gaps are in terms of climate action and gender equality. Another area where progress is lagging is young people: close to a third don’t have a job or any kind of education. Also, when it comes to workers in the global supply chain, there are real issues on human rights and living wages.

So, the world still faces huge challenges. But it’s good to see that almost 10,000 companies around the world, large and small, have joined the U.N. Global Compact, the largest corporate sustainability initiative in the world, and 81% of them tell us they have taken action on the SDGs.

What else are companies saying?

We just published a study with Accenture in which we asked more than 1,000 CEOs to assess the state of sustainability and share how they were adopting the global goals. While 99% of the largest companies believe that sustainability is critical to their future success, just 21% think business is doing enough. They cite “absence of market pull” and the trade-off between cost pressures and long-term strategic investment as the main barriers to overcome.

How important is CEO involvement?

It’s a prerequisite. Among participating companies, we find that the vast majority have CEOs who are personally involved and see this as a strategic business innovation agenda, where the Ten Principles of the U.N. Global Compact and the SDGs are very much setting the direction for the future of their firms. We recommend that the principles and goals be integrated in the whole corporate strategy; in the company’s articles of association; in its purpose, vision, mission and values statements; and in its governance, including the board agenda, board competencies and board responsibilities.

What else do you recommend?

One best practice we’re seeing is companies taking a small selection of goals they find most relevant to their business and then anchoring their strategy in them, building targets into their balanced scorecards and rolling them out across their operations. This ensures that business strategies, investments and management systems are operating under the same set of principles and working toward the same set of goals.

What’s your advice for those taking their first steps?

We operate more than 60 Global Compact Local Networks in over 160 countries under the motto of “Making Global Goals Local Business.” So, a good way to start is to contact your local network and find out how to participate in local activities and events. There are a number of easy-to-use tools on our website, including the Blueprint for Business Leadership on the SDGs. Above all, you need to determine which of the goals you are going to tackle as a company and how to integrate them into your business. And if you want to work on a particular issue, such as climate action or gender equality, we can offer specific guidance as well.

“Above all, you need to determine which of the goals you are going to tackle as a company”

Is adopting the goals feasible for smaller firms?

There are great examples of small companies adopting the goals. I think adopting a responsible approach is more of a mindset issue than a resource issue. Developing the company into a purpose-driven organization to create a better world is simply a choice that has nothing to do with size. Small companies may do an easier version, perhaps picking fewer goals but really using them as unique selling points and boosting engagement. Many of the companies taking some of the most innovative measures in sustainable food or sustainable fashion, for example, are small startups that have wholeheartedly embraced the sustainability agenda. Indeed, smaller companies are sometimes able to be more innovative than larger ones when it comes to these issues. When companies become too big, it can be harder for them to integrate or embed these concepts into their existing systems and to do it in a proper way that is credible.

Which global trends concern you personally?

The No. 1 trend that worries me right now is the geopolitical instability that we are seeing in many forms, like trade wars. And it’s not just me: 63% of the CEOs we surveyed are also significantly worried about how this instability will affect their ability to run their business successfully. Many CEOs know they should be doing more — 71% believe that with increased commitment and action, businesses can play a crucial role — but, like I said before, only 21% feel they’re doing enough. So this mix of a serious geopolitical situation and companies not being sufficiently ambitious is problematic.

What do you say to critics who suggest that companies are only doing this for PR?

From day one, we’ve been absolutely clear that the goals must be anchored in principles. This means that all your strategies, operations, policies and procedures must be rooted in a culture of integrity, based on the conviction that your long-term success depends on upholding certain fundamental responsibilities to people and to the planet. It can’t just be a few colorful items in an annual report; it has to be genuinely embedded into your business or it won’t work.

Ultimately, it comes down to a choice. You can choose to do very little and just make it look like you’re doing the right thing, but risk it being seen as window dressing. Or you can choose to take it seriously and give it 100%. It’s the same with everything in life, right? With less than 4,000 days to go until the 2030 target, it’s time for everyone to step up.

Interview by: Larisa Tatge

7 leadership qualities for the goals

04Countdown to 2030

Making progress on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) requires these special qualities in a leader. Ask yourself these questions and make necessary improvements in any areas where you see yourself lacking.

Source: Based on the U.N. Global Compact’s Blueprint for Business Leadership on the SDGs (2017) and complemented with original research by Phu Nguyen Thien, Anneloes Raes and Yih-teen Lee, done in collaboration with leaders of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) who participated in a senior leadership development program customized for them at IESE (2019).

1) Intentional

Are the SDGs an integral, deliberate part of your company’s strategy, incorporated into your long-term business goals?

From the means of value creation to how you manage your people and supply chains, are the Ten Principles and your chosen SDGs driving your company from the highest levels?

2) Ambitious

Are the targets you set sufficiently ambitious and based on accepted scientific thresholds?

Is your company challenging existing practices to transform how business is done?

3) Consistent

Is support for the SDGs recognized across all organizational functions? Is ethical behavior embedded in your senior management teams?

Is there consistency and alignment between what your company says – through its public voice, advocacy and communications – and what it does throughout its business, with regard to the SDGs?

4) Collaborative

Are you forging partnerships with other businesses, governments, civil society organizations, academia, investors and local communities?

Is there shared decision-making in those partnerships so the actions are being co-owned?

5) Accountable

Do you hold yourself accountable for the impact your company has on people and the planet?

Are there risk management processes and systems in place to prevent adverse impacts, with mechanisms to remedy any grievances?

Are you transparent with stakeholders and acting lawfully in accordance with international norms, even if these are not legally mandated in the country where you do business?

6) Resilient

Are you able to stay calm and determined when facing challenges and setbacks in the pursuit of ambitious SDGs?

Have you developed effective mechanisms for coping with frustrations and difficulties when immediate results are not yet visible?

7) Inspiring

Are you motivated by a higher-level purpose and motivating others through your shared pursuit of the SDGs?

Do you articulate your vision and mission clearly to guide yourself as well as others, so that people are inspired to give the best version of themselves for the good of the collective whole?

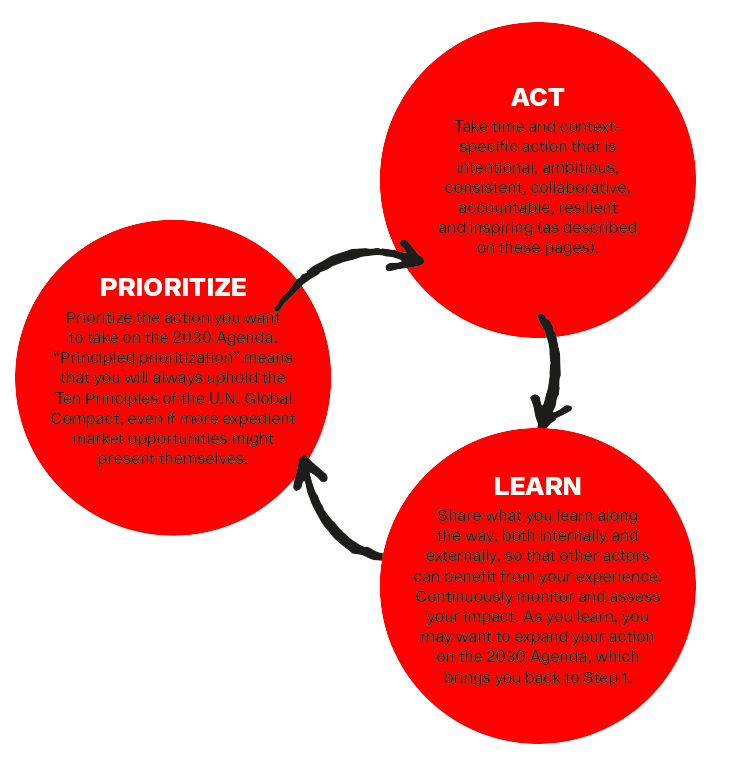

3 steps for leadership on the goals

As the business environment changes, your leadership must evolve accordingly by repeatedly going through these three steps:

Juvencio Maeztu: “We’ll always do things because we believe they’re right”

05Countdown to 2030

Juvencio Maeztu is Deputy CEO and CFO of Ingka Group, which manages IKEA operations.

Juvencio Maeztu calls himself “an aspirant.” Despite a long track record of managing retail operations and finances for IKEA since 2001 in Spain, Portugal, the U.K. and India, Maeztu happily admits that he still has a lot to learn. There’s no shame in saying so, he says, “because it gives you much more confidence and energy about learning. And we all need to embrace learning.” Having earned an MBA at IESE and now sitting on IESE’s International Advisory Board, Maeztu is currently on a learning curve along with many other CEOs around the world as they collectively apply the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to their businesses. Here he shares what he has learned so far.

How seriously do you think companies are taking the Sustainable Development Goals?

Companies used to view sustainability as a dilemma: if we do this, it won’t be good for our P&L or it might compromise customer preference. But when we stop treating sustainability as an activity and instead anchor it in the core values of the company, then those dilemmas go away. Talking with colleagues around the world, I find more and more have reached that point in their thinking. Now the question is: how can we make sustainability happen in a faster way?

How is IKEA answering that question?

It helps that our mission has always been “to create a better everyday life for the many people,” which is more relevant than ever. To that we’ve added a People & Planet Positive agenda with specific goals to transform our entire business. This is what I mean by anchoring the SDGs in your core values. It’s also a process of responding to the values of society, and determining your company’s role in that society. I look at my children: their generation is leading the way on sustainability issues. That puts a big responsibility on companies like ours to welcome new generations and allow them to influence our future direction.

So, consumers and employees are driving this agenda…

It’s the coming together of our values and vision with the demands of society and new generations. As they make these demands, we have a responsibility to provide solutions and integrate them into our business model. So, when IKEA makes products, it’s about the design, the quality, the functionality, the price — and the sustainability. We have to consider all these dimensions. And when we do this, the outcome is a sustainable business model that can help the people and the planet.

How do you ensure sustainability stays core, and avoid mission drift?

Three ways. The first has to do with the company culture you build and the expectations you set, starting with the people you hire. We’re obsessed with recruiting by values, not curriculum. If you hire people who already share the same values of wanting to build a better world, then everything else becomes easier. In this regard, we find the blind CV is a good technique to find people — not profiles but people. Second, as I said before, sustainability has to be embedded in the business model, in the strategy, in the operations, in all planning, across all layers. You can’t have a business plan and then a few CSR activities on the side. Finally, you have to report. As the saying goes, what gets measured matters. And after you measure, you have to follow up.

How should companies approach reporting?

Reporting is not just to fulfill some statutory obligation; it’s to show how you’re doing with regard to your mission. We don’t issue a financial report and then a sustainability one. Because all our KPIs are measured with sustainability, we combine numbers and stories in one document. I would stress that the main objective of reporting is not to justify things externally (though, obviously, subjecting your performance to public scrutiny is a good thing) but to challenge your colleagues and those working inside the organization to keep moving the company forward in its mission.

“You start with your values and doing what’s right, and after that you consider how”

What’s your advice to companies trying to transform themselves to become more sustainable?

First, transformation doesn’t have to mean a 180-degree change. For us, transformation is about deciding what will never change, which for IKEA is about having a deep, genuine interest in the way you live at home. We’ll never touch that. And we’ll always do things because we believe they’re right. Then, it has to make business sense. But notice the sequence: you start with your values and doing what’s right, and after that you consider how.

Second, have a transformation agenda. Ours is called “10 Jobs in 3 Years.” It’s about identifying 10 jobs that represent strategic choices where transformation has to happen. What new roles do we need in our stores to position IKEA as People & Planet Positive? How do we need to transform — not improve but transform — the way that IKEA is today to what it will need to be in the next three years? We could have said “10 jobs in 10 years” but then it just becomes an ambition. Three years forces actionable strategies. That’s how transformation happens.

Third is having humility and willpower. Why this combination? Because when going through transformation, you’ll have to act fast in the face of a lot of unknowns. You need to be humble enough to accept what you don’t know, and then super determined to go through with it. It would be very dangerous if you felt you had to have all the answers or if you spent limited time trying to find the perfect solution.

The circular model is one of your goals. How does a retailer make that work?

It goes back to values. Take one of our business principles: quality. The higher the quality of a product, the longer it’s going to last, and the less need there will be to buy a replacement. Does that mean we should stop investing in quality? Of course not. We invest in quality, despite the apparent trade-off, because it’s the right thing to do according to our values.

In designing with circular principles, if we do something in plastic, it has to be recycled plastic, or if we do something with wood, it has to be FSC certified. It can also be recycled at the end of its life and sent back into the supply chain. In India, we started a project to turn food into compost, which was given to female entrepreneurs who grew vegetables, which were then used in IKEA stores. We’re doing things like that to really close the loop.

We’re also testing services to give a second life to IKEA products. Through a sharing platform, people can list, sell, buy or rent secondhand IKEA furniture or obtain spare IKEA parts. In 2018, we repackaged more than 8 million pieces of furniture and redistributed more than a million spare parts to consumers.

From the way the product is made to the end of its life and everywhere in between, we’re exploring many activities. And the bottom line is, this doesn’t compromise your turnover. In the end, by being more relevant to many more consumers, revenues will grow.

What would you say to a businessperson who might respond with: “But you could make even more money doing it the old way”?

I’d say the old way has an expiry date. Either you focus on making a positive contribution to the world or you’re gone.

Goals made EASIER

06Countdown to 2030

Do your projects create social, environmental and economic value? Use this framework to find out…

By Joan E. Ricart and Pascual Berrone

The magnitude and ambition of the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) mean that no single entity can go it alone; achieving the 17 goals requires a joint effort. In fact, SDG 17 calls for “partnerships for the goals,” recognizing that making true progress on sustainable development will entail multistakeholder partnerships in general and effective public-private partnerships (PPPs) in particular.

PPPs are long-term collaborative relationships, by design, making them natural vehicles for delivering on the goals. They leverage the resources and competencies of the private sector — a willingness to take risks, assume upfront costs, connect markets and create jobs — and then bring them to bear on the provision of a public service or good. And the value they create is not just economic but social and environmental. This “blended value” approach is inherently aligned with the essence of the SDGs.

Despite these apparent advantages, there is limited research on how PPPs can advance economic, social and environmental goals in parallel. And what work has been done tends to focus on the economic dimension only. We wanted a different model to assess PPPs’ contribution to the SDGs beyond the notion of value for money. So, we developed an evaluation model that we call EASIER, a mnemonic device for these six dimensions:

Engagement of stakeholders. Does the project count on the participation of all relevant stakeholders (e.g., suppliers, local community groups, unions, ecologists)? Involving stakeholders, particularly at the outset of a project, can be a decisive factor in its success. This implies not just making information public, but actively seeking stakeholder input through surveys, public hearings or web forums, and then incorporating their values and preferences in subsequent decision-making.

Access. Does the project increase access to services in the interest of diverse populations? The more people who can benefit, the greater the impact on well-being, social justice and equality.

Scalability and replicability. Can the project be enlarged or expanded to meet growing demand, without significant social or environmental costs? How transferrable are the results to other geographies? Capacity building is key: offering training and education, and then transmitting the know-how and lessons learned to other stakeholders.

Inclusiveness. “No one left behind.” Is the growth and development equitable and inclusive, starting from the design to the building to the operation of the project? Can it be accessed by all individuals, especially the most vulnerable? Does it promote women’s empowerment?

Economic impact. In measuring the project’s economic impact, it’s not just how much money was saved. Rather, it’s how many local jobs were created — decent jobs, with long-term employment prospects and the potential to reduce inequalities. Is there technological upgrading and technological transfer, fostering research and innovation, and helping left-behind areas to catch up? Does the project promote more sustainable, ecological patterns of consumption and production?

Resilience and environment. How well does the project meet the needs of the present without compromising future generations? Is there capacity in the system to respond to and recover quickly from disaster? Does it seek to preserve the natural environment and take action to combat climate change?

Our EASIER model offers a simple yet holistic diagnostic tool to assess projects, particularly during their design phase. It’s timely and relevant, as the United Nations is studying how people-first PPPs can be used as powerful tools to achieve the targets and goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Although fulfillment of the goals may seem challenging, by paying attention to the six dimensions we highlight, the job should be a whole lot easier.

Read more: “EASIER: an evaluation model for public-private partnerships contributing to the sustainable development goals” by Pascual Berrone, Joan E. Ricart et al. is published in Sustainability.

This Report forms part of the magazine IESE Business School Insight #154. See the full Table of Contents.