Leaping ahead

01Lessons from Africa for making strides in business

By Ermias Mebrate Mengistu

Director of the Africa Initiative at IESE

The West knows best: how often have we heard this? There is a widespread assumption in the business world that Western practices can be applied in all contexts. Non-Western approaches are niche while the Western way is the universal, default setting for doing business. However, as Ugandan entrepreneur Peter Nyeko asks in this report, what happens when reality doesn’t neatly line up with Western frameworks? What then?

IESE professor Yuliya Snihur and co-authors recently reviewed a decade’s worth of papers published in the Journal of Management Studies and found only 12% of them came from non-Western contexts. In some years, the percentage was as low as 3%. According to the authors, the marginalization of non-Western voices is a travesty, impoverishing our understanding of the distinct cultural, political, regulatory, organizational, relational and ethical contexts needed to succeed in market contexts that are increasingly central to our global economy.

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2024, former U.S. congresswoman Jane Harman said, “We still think of Africa as an afterthought,” when in fact Africa “has a lot to teach us about sustainability and is in much better shape than many — certainly the United States.” She went on to challenge the WEF audience: “Why don’t we be a little more humble and imagine that our problems are worldwide, and that (solutions) could be sent our way from there?”

This is the thinking behind this special report in which we showcase insights from Africa, drawing on the expertise of our alumni and the business schools that IESE helped to establish on the continent: MDE Business School in Ivory Coast, Strathmore University Business School (SBS) in Kenya, and Lagos Business School (LBS) in Nigeria.

In line with its mission to develop leaders who strive to have a deep, positive and lasting impact, IESE has been actively engaged in Africa since the early 1990s, helping to establish, support and strengthen a top-quality, rigorous and values-based management education infrastructure there. Today, all three institutions — MDE, SBS and LBS — are widely recognized as leading business schools on the continent and beyond, with LBS consistently ranked among the top 50 Executive Education providers in the world by the Financial Times.

Our continued close collaboration on research and academic exchanges with all three schools, spearheaded by IESE’s Africa Initiative, allows us to shine a light on innovative solutions coming out of the continent that can help address common global problems.

Africa is “leaping ahead” in many ways and we share inspiring stories from the continent

One of the most well-known concepts to come out of Africa is “leapfrogging.” In other words, in the absence of certain institutions or infrastructures that might be taken for granted in the West, African businesses skipped those intermediary steps entirely and went straight to the development of an innovative solution, inventing novel business models in the process. In the absence of landlines and bank branches, for example, they went straight to mobile phones and mobile banking.

But there are other ways that Africa is “leaping ahead.” Besides banking, we feature exemplary executives and companies in agriculture, healthcare, retail and infrastructure, particularly in relation to energy. Their stories underscore the power of business model innovation and unconventional entrepreneurship in tackling Grand Challenges — those big problems, like climate change and energy poverty, that require even bigger thinking to solve.

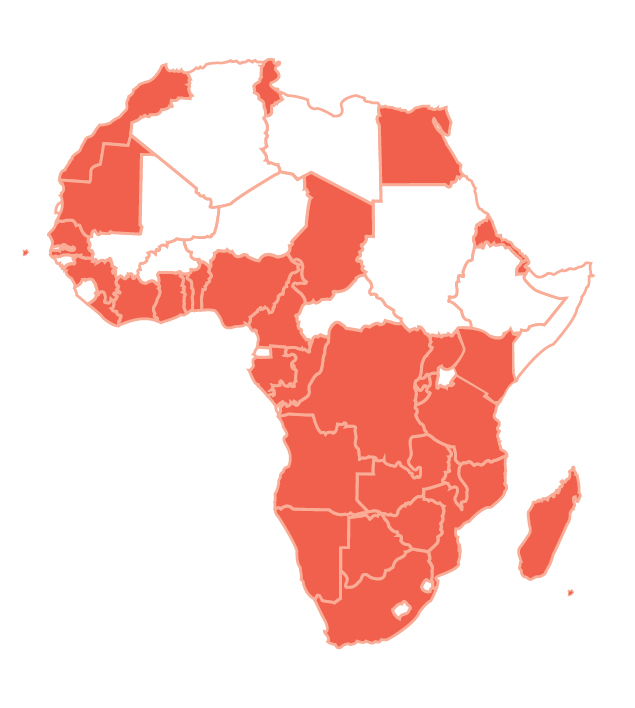

Of course, as Snihur acknowledges in her paper, it’s hard to generalize about vast geographies with so many cultural nuances and differences. Just as “the West” imperfectly encompasses everywhere from Europe and North America to Japan under its umbrella, likewise Africa, as the world’s second-largest continent, comprises 54 different countries, with South Africa sometimes lumped in with the West. For our report, we have endeavored to find best-practice examples whose activities span the north and south, east and west of the continent, providing a flavor of Africa’s diversity.

We also strove to feature homegrown examples: businesses born of the continent, rather than Western multinationals operating there (although they, too, are finding tremendous opportunities in Africa).

We commend this report to you. We hope it inspires fresh thinking on sustainable growth, shared value and social impact — concepts that we believe are applicable to any corner of the world.

Infrastructure: We get things done

02Lessons from Africa for making strides in business

Sameh Shenouda is Executive Director & Chief Investment Officer of Africa Finance Corporation (AFC) and a participant in the IESE Global CEO Program. Ahmad Rahnema Alavi is a Professor of Financial Management at IESE.

They say every failure is a step to success, and that’s certainly true for Sameh Shenouda (pictured left). With decades of experience in infrastructure investments and fundraising in capital markets, it was while working for Blackstone that he was tasked with setting up Zarou, a standalone venture for investing in renewable power assets in emerging markets.

“But they didn’t really understand emerging markets,” he recalls. “And then COVID hit, and the projects I presented for investment got turned down. I didn’t want to spend years of my life presenting projects that never saw the light of day.” Which led him to join the Africa Finance Corporation (AFC) in 2021.

AFC is truly pan-African, counting 43 African member states making public-private investments in 36 African countries to deliver transformational infrastructure projects in five priority sectors: power, transport, heavy industries, natural resources and telecoms & technology.

As an Egyptian, working for a financial institution created by African states to provide infrastructure solutions for African states was highly appealing: “I always felt there was a need to bridge major infrastructure gaps and boost productivity and economic growth on the continent. And AFC, to put it simply, gets things done.”

Whereas other investors might shy away from writing checks for early-stage infrastructure development projects, AFC closed 20 transactions in 2023 alone. “That’s a huge number of transactions, especially by African standards,” he says. “There are very few investors who understand the African environment and do a lot, rather than talk about it and do very little.”

IESE Prof. Ahmad Rahnema Alavi (pictured right) is aware of the challenges. He previously held the Fuel Freedom Chair for Energy and Social Development at IESE, dedicated to researching energy solutions for Africa in critical areas such as transportation and power generation. He was keen to find out how AFC is closing the infrastructure gap, especially considering that an estimated two-thirds of the infrastructure required for Africa’s sustainable development is yet to be built.

Ahmad Rahnema: As I understand it, for every dollar AFC invests in a project, you attract another $5-$6 from third-party investors. In 2023, AFC disbursed $1.5 billion in investment, despite a challenging operating environment, including high interest rates, inflation, rising debt, slow growth and geopolitical uncertainty. How do you do it?

Sameh Shenouda: Let me take you through the process. The biggest bottleneck in moving from the concept stage to a project operating on the ground is early-stage development. So, if the project is to build a power plant, the biggest hurdles are negotiating with the governments and other vested parties to get the licenses, the land rights, the power purchase agreement, the Engineering, Procurement & Construction (EPC) contract, and so forth. Once you have all those key agreements signed, then you are able to attract other lenders or equity investors more easily.

Our projects are structured as public-private partnerships, counting 43 African states as members, which enjoy preferred creditor status, immunities, tax exemptions and other privileges. We’re the second-highest rated entity in Africa, with an A3 rating, which means that our cost of funding is much lower and our credit rating is much better than many countries’. This is a key differentiator for AFC: Because we de-risk the opportunity, it becomes a bankable project attractive to investors, making it easier for them to invest in the project.

When we built a port in Gabon with partner capital, it happened this way. A private equity fund backed by a number of European investors came on board, but they told us they wouldn’t have done it earlier when it was still in concept; it was only because we had developed other ports and had another one being developed that made them confident to invest alongside us. We see this a lot in all our sectors.

AR: Do you find this has a snowball effect, or what we might call, if it were digital, network effects, where the more projects you do, the bigger AFC grows, which builds legitimacy, feeding a virtuous circle of more and more investors?

SS: Yes and no. At the project level, yes. This is reflected in how fast we have grown. Since Samaila Zubairu joined as CEO five years ago, the balance sheet has grown from $4.5 billion to $13 billion. That growth is easy to demonstrate.

“There’s a lot of African money interested in what we do because they understand Africa”

The “no” part is that so much money in the world right now is looking for climate-related impact investment. However, Africa isn’t on the radar of many funds. What’s really frustrating is that Africa is only responsible for 3% of global carbon emissions, yet we suffer the consequences of global climate change. What we need is basic infrastructure, in addition to carbon-reduction projects.

Meanwhile, Africa has the world’s second-largest forest. One of the world’s biggest stores of critical minerals that go into battery manufacturing. We have a lot of sun across the north and a lot of wind along the coasts. Still, the money is not flowing fast enough our way. There’s a lot of African money interested in what we do because they understand Africa. But it’s a shame we don’t see more non-African funding coming in.

AR: Speaking of climate change, are you seeing your investment portfolio mix tipping away from fossil fuels and toward more renewables?

SS: One of the challenges of Africa is that there are 54 countries, and outside of a few countries such as South Africa, Egypt and Morocco, there is no unified, large-scale renewable energy. Three years ago, we had three renewable energy projects, and we felt we could not be who we are and not attract party capital into mega renewable projects. So, we presented a strategy to our board to scale up our renewable energy activities, skilling up through acquisitions, partnerships and greenfield development, to create a multiple-asset, multiple-country, diversified platform large enough to appear on the radar of the larger international players, enticing them to come and invest alongside us. Instead of single assets, we essentially created a conglomerate of diversified assets.

Fast forward three years, and we have invested in Infinity Power in Egypt, and with Infinity acquired Lekela, a wind-energy company. Following these two investments, with our partners, we are the largest renewables player in Africa. And we have the right partners with us — the right set of shareholders, a strong management team, operating assets that are diversified geographically. Now, people are coming to us: governments want us to develop more projects for them, and investors want to be part of that success story.

AR: How did COVID-19 affect the investment landscape? As in other parts of the world, did the pandemic spur the setting up of more local infrastructure as it became harder to ship resources abroad for processing?

SS: It did. Africa has major global shares of key minerals and metals, including bauxite (30%), manganese (60%), phosphates (75%), platinum (85%), chrome (80%), cobalt (60%) and titanium (30%). All are generally exported in their mined state to Asia for processing into batteries, electronics and chips. COVID was a major disruption to this supply chain and a wake-up call, not only for us, but for everyone.

Part of our mandate is to capture as much of the value as we can within the continent. Think about an electric vehicle: maybe 2% of its value comes from the mining of raw materials, whereas the balance represents the processing of those materials and the production of batteries. What if we could reduce shipping the mined material all the way to Asia, and then re-exporting the battery or the electric vehicle from Asia to Europe and the U.S., all of which add weeks of shipping?

“Part of our mandate is to capture as much of the value as we can within the continent”

We commissioned a study to find the best location to build refining capacities closer to where the mines are, and bringing everything together in a place where there is power and a port. On paper, it seems the right solution, but the reality is very complex. You need to think about where the infrastructure is, where the power is, the capacity of the country, the rule of law, all these things.

AR: I suppose this is where having governments as AFC members helps?

SS: It does. We have access to the decision makers, which helps in opening doors. However, if there’s no regulatory framework to help get this done, it’s challenging. For example, in the copper belt of Zambia and the DRC, the governments asked us to help. But just having the natural resources is one thing; if there’s no road or rail to move the resource, then it’s not worth it. So, AFC is now involved in one of the biggest landmark projects in Africa, which is the Lobito Corridor, a 1,300km railway line that will run from Zambia to the Atlantic Ocean in Angola, backed by the European Union and the U.S. government, as well as the African governments along the route. For us, this is a transformational project, unlocking massive opportunities, not only industrial but also for tourism.

AR: Some investors might run scared, given the political instability of some countries.

SS: For an outside investor, the risk perception seems high, but for us, the real risk is lower; it’s the environment we live in. And regardless of who’s in power, the need will always be the same. Obviously, there’s a risk of a new government not understanding the importance of what we do, but there’s an education process. We understand the landscape very well and we’re resilient.

AR: Resilience is a key quality nowadays. What other qualities are needed to navigate this new world order?

SS: You need to understand the markets you’re working in very well, and if you don’t understand them, then partner with someone who does. And make sure you’re like-minded: you don’t want a partner who will walk away at the first sign of trouble. You also want to front-load the risk, as I explained before. Some people treat risk as investing in five projects, assuming they will lose money on four, but the one that succeeds will offset the four failures. We don’t do that: we assess the probabilities of success right from the start, and once a project enters our pipeline, we throw all our weight behind it. For every project we’ve done, I think our hit rate has been 80-100% because we reduce the risks at the beginning.

“It’s about having an entrepreneurial spirit of getting things done and being impactful”

In terms of individual qualities, it’s about having an entrepreneurial spirit of getting things done and being impactful. Reframing every problem as an opportunity and being agile.

AR: Which AFC project has been the most impactful?

SS: Every single one! No matter the sector or how much money, every project has had a major impact on people’s lives. That’s why I’ve always worked in emerging markets, mostly in Africa. I want to do good while doing well, and seeing our investments delivering real results is incredibly satisfying.

AR: Africa seems to be at the center of the solutions of many common issues facing the world today, whether it’s renewable power or food security. And yet investments, capital flows and the asset allocation of sovereign funds, pension funds and insurance companies remain limited for Africa — it’s generally not on their map. If Africa holds the solutions, how do you change that?

SS: The tipping point has to be convincing those funds to put, not 1% but even just 0.1% of their asset allocation into African infrastructure. That would be a gamechanger. People also need to change their view of Africa from an aid-and-famine picture to a real partner in strategic sectors that has people who can get things done.

From where I sit, all I see is the potential, the opportunities, the development need. I see a growing, young, smart population who doesn’t get enough opportunity. Africa has the youngest population in the world. Instead of having them thinking of migrating abroad, we can develop their capabilities and create jobs on the ground, which would support the world economy generally. All of the pieces of the puzzle are there; it’s just a matter of putting those pieces together.

AFC could be 10 times the size it is now and there would still be an infrastructure gap in Africa. AFC has been very successful at doing what it’s doing. But we can always do more.

Lessons from Uganda

Peter Nyeko (pictured) is Co-founder & Managing Director of Mandulis Energy. A cleantech entrepreneur, he is a participant in IESE’s Foundations of Scaling Program and he spoke on “Harnessing entrepreneurship and impact investing: driving solutions for environmental and climate change challenges” as part of the Doing Good Doing Well conference held at IESE Barcelona in March 2024.

Based on the circular economy and using satellite and AI technologies, Mandulis Energy takes a nature-positive, hybrid approach to bioenergy for carbon capture and storage, biomass carbon removal and storage, and high-quality biochar-based carbon removals.

In doing so, it delivers sustainable, affordable and reliable energy access, along with clean cooking and biochar organic fertilizers for soil regeneration.

Mandulis leverages climate finance to decarbonize development by deploying sustainable infrastructure that powers agriculture and enables industrial supply chains to become more green, robust and inclusive.

Started in Uganda in 2012, Mandulis is building synergies to further scale and replicate its impact across Africa, expanding into Botswana, Nigeria, South Africa and Zambia, as well as across Asia and Europe.

“It has been back-breaking work,” says Peter Nyeko. Here are the lessons he has learned.

Keep an open mind

Sometimes reality on the ground goes against what you learned in business school: it doesn’t follow Porter’s Five Forces. That’s when you need to stop offering products or services that have no value to a community and start figuring out what they do value.

To deliver electricity, it was the realization there was no way the community could afford the electricity and therefore no way to make a profit, so Mandulis had to figure out how not to be an electricity company. That changed the entire business approach.

Your customer may not be your customer

Mandulis initially thought of selling clean products to reduce the cost of cooking, before realizing the most valuable thing was the ash coming out of stoves. Once the focus shifted to the waste coming out of the power plants — the CO2, for example, which Coca-Cola can use in its bottling, making Coca-Cola the customer — Mandulis was able to turn a vicious cycle into a virtuous one. The farmer whom they thought was the customer stopped being the customer and became a co-stakeholder as a source of production instead.

Don’t fail fast, fail forward

It’s a process of continuously improving and educating investors to walk the journey with you.

“Before doing this, I worked in aerospace, where you spend years testing a product to make sure it’s not going to fail. I use the same mindset, looking at each small step as a massive step for humankind. You do lots of different feasibility studies, year after year, gathering feedback and carefully documenting processes, until you finally tick every box, and it scales and takes off.”

“It’s a dogged focus, not on one solution, but on the success of whatever solution emerges at the end of the journey.”

Find like-minded partners

Most global companies have made sustainability commitments, so there’s a massive opportunity there, because those companies will be looking for opportunities to demonstrate their commitments. Partner with other brands and make alliances, which will help you scale some solutions.

Be human

Spend time with the community you hope to reach. Connect with them as human beings: figure out what they like and how what you do as a company can steer them away from what makes them sad and toward what makes them happy.

“We hold open days, with lots of fun activities, but also lots of honest feedback, which helps us learn more about where we are, where we’re going and where we should be going as a company.”

Invest in the community: Mandulis invests in land alongside the farmers to understand directly what their challenges are. “By walking in their shoes, we not only understand them better, but they also take us a lot more seriously.”

READ ALSO: How Eghosa Oriaikhi Mabhena is trying to improve energy access and transform the energy industry in Africa.

Agribusiness: Sowing change for farmers

03Lessons from Africa for making strides in business

Ayodeji Balogun is the Group CEO of AFEX and alumnus of the IESE Global CEO Program for Africa 2019. Donald N’Gatta (IESE PhD 2021) is a Professor of Accounting at MDE Business School in Ivory Coast.

In many countries, farmers get the short end of the stick. They grow commodities like cocoa and coffee, soybeans and sorghum, which they then have to harvest, store, transport and hopefully sell for a good price — if they can access a market and if the trade price is high enough to make it worth their while. And when you’re talking about small family farms, those are big ifs.

From Europe to India, 2024 began with waves of protests by local farmers, voicing complaints all too familiar to their African counterparts: lower prices for their goods, higher costs, too much bureaucracy and unfair competition from other countries, all of which were crippling their ability to make a fair living.

Ayodeji Balogun (pictured left), whose dad was a farmer in rural Nigeria, understands these complaints well — so well, in fact, that in 2014 he launched AFEX Commodities Exchange to intermediate between commodity producers and buyers, and make the process more profitable and sustainable for all.

Through a tech-enabled trading platform that updates commodity prices daily, farmers can produce the right quantity and quality that the market needs, and that is matched with buyers for processing and/or reselling.

AFEX also provides logistics support through an accredited network of warehouses, key for ensuring that farmers’ perishable goods make it to market.

They also settle deals in cash on the spot — a boon for smallholder farmers — though by putting commodities trading in the hands of users, trades can be carried out, deliveries traced and credit extended through a mobile app, empowering farmers even further.

“Think of it like Amazon,” explains Balogun. “Somebody is selling, somebody is buying, and somebody has to pick it up from the warehouse and deliver it. That’s essentially what we do: we’re the Amazon for commodities.”

Having expanded eastward to Kenya and Uganda, AFEX is now expanding westward from Nigeria to Benin, Togo, Ghana and Ivory Coast.

As a Professor of Accounting at MDE Business School in Ivory Coast, Donald N’Gatta (pictured right) is interested in Balogun’s process of expansion and finding out how agritech like AFEX’s can help create sustainable value for farmers whose challenges are being compounded by climate change.

Here, they discuss an alternative vision for agriculture that puts farmers first.

Donald N’Gatta: Smallholder farmers typically lack vital resources, whether equipment, capital or education. How does AFEX help them?

Ayodeji Balogun: African smallholder farmers are no different from anyone else: they make rational economic decisions, trying to optimize revenue within the resources available.

It’s the same decision-making process I go through if I were to travel to my hometown 300 kilometers away. The fastest way is to fly, but if I don’t have the cash to pay for flight tickets, I go by car, and when I can’t use a car, I use a bus, and so on.

A farmer does the same: he knows he needs to plant on time, using the right mix of fertilizer and hybrid seeds, and his productivity will go up and he’ll make more revenue. And if he has the cash, that’s what he’ll do. But when he doesn’t have the cashflow, then he rationalizes and says, “Let me use the seeds from last year, and I’ll use three bags of fertilizer instead of six.” That affects his productivity but it is the optimal rational economic decision for him to make at the time.

What we do is go back to the fundamentals. Who is this farmer? Is he an economic actor? Is he financially included? Can we understand his productive assets: his land, what crop that land can best produce, would it be more efficient for him to be part of a collective?

And then we provide a bundle for him, whether a loan so he can buy seeds or fertilizer, or upskilling and training, or help with his choice of when to sell. Some will sell at the price at harvest; some will wait if they feel they can get a higher price in a few months’ time, and use a forward contract.

We operate on the assumption that farmers are brilliant. They’ve been doing their job year in, year out, for decades. Although we offer them loans, they’re not farming under contract with us. They own the commodity, and they choose what they want to do with it. Our job is to give them more tools for them to be able to exercise their own rational economic choices.

DN: And your technology platform enables all this information to be aggregated and shared, correct?

AB: Correct. We start with the registration and profiling of the farmers and archiving their data. Then they take a loan. Someone works with groups of between 200 and 400 farmers to track the data on loans and repayments and to close the trade on behalf of the farmer. That trade goes to the exchange, reporting the value of the commodity on any given day. The buyer could be a food company or an export company. That value then goes to the farmer, with a fee paid by the buyer and the seller on the exchange.

DN: How does this differ from traditional commodities exchanges?

AB: Other commodities exchanges operate like stock exchanges, where you trade, there’s an auction, you try to beat an offer, and the winner takes all. Or there are futures exchanges, which cater for big buyers and big trading houses and financial institutions. But until AFEX, there was no model on the continent that took a view of the productivity of the farmer, the broader ecosystem and the logistics in between, and tried to connect all that in a holistic way.

“What are the biggest problems for farmers? How can we create something that addresses their needs?”

When we set out to create our commodities exchange, we thought it was about building the biggest, most expensive technology platform. But upon engaging with the market, we realized the real problem we needed to solve was reaching the outermost perimeters of the supply chain; that if you don’t solve the problem of the last mile — the quality, quantity and productivity of the farmers — then you don’t have any exchange without any volume flowing through it.

That was the point where we started to innovate and say: What are the biggest problems for those farmers? Which problems can we solve for commercially and at scale? How can we create something that addresses those needs?

DN: Was offering storage facilities part of that desire to move closer to farmers’ needs?

AB: Yes but not to be in the business of storage, which other people can provide, just as we are not the only ones to offer loans to farmers. Rather, we provide storage as a service with retail to the farmers who then pay upon exits when they’re dispatching or selling the commodity.

Our innovation was really looking at what existed and then connecting all the various fragmented solutions together into a holistic, integrated, inclusive solution that has farmers, traders and processors together.

DN: How do you manage price volatility so local farmers are less exposed to price fluctuations?

AB: We focus on 10 commodities, of which five (maize, rice, sorghum, soya and wheat) are staples that are produced and majorly consumed locally. The other five (cashews, cocoa, coffee, ginger and sesame) are more export oriented. These two baskets have different price volatility risk profiles.

Staple commodities behave rather predictably, because all farmers plant and harvest around the same time, with little price modulation until the end of season when prices start to go up before the new harvest comes in. Then you have a reset and a new price discovery call for the next season.

For international prices, there are more fluctuations due to speculatory activity on futures markets as well as the transmission effect of what happens in the wider world on those prices.

One of the things that spurs us, as innovators in this market and also being a pioneer pan-African commodity exchange, is that we need to move price discovery closer to the market of origin. Whether COVID-19 or Brexit, these external macro crashes have a huge impact on prices but zero correlation with the cost profile of the local farmer.

Our view is that we need to build markets that are closer to origin and where farmers can get fair value on supply-and-demand fundamentals rather than being subject to extraneous macros that have very little correlation with farmers’ cost of production.

DN: This seems to be part of a trend of relocalizing trade.

AB: I see it as glocalization. What we don’t want is an extremely just-in-time world where everything is traded futures, everything is overcommoditized, and the story of the producer and where these commodities come from is reduced to a price sticker on an exchange.

That’s the world we don’t want — a world so stretched for profits that it puts the sustainability of the producer and of the environment at risk.

So, if I buy a pineapple in Europe, I want to know what percentage of the price I’m paying goes to the farming community that produces it. How was it planted and harvested? Then, it’s my choice of which I want to buy, and I could choose to pay a premium because I know the details of who produced it.

DN: There’s some research evidence that doing business in Francophone Africa is different from the rest of the continent. What did you find during your expansion process?

AB: I’m a big fan of IESE strategy professor Pankaj Ghemawat’s CAGE framework (see sidebar below). If you look at our expansion, we first went to Kenya because of CAGE similarities: the English language, the British cultural heritage, the common law legal system. Uganda was next for similar reasons, and also because of the existing bilateral trade relationship between Kenya and Uganda, and the ease of flows, in trade, people and flights, between those countries. In expanding west to Ivory Coast, the geographical proximity makes sense, even though it may be culturally and linguistically different.

CAGE framework

Distance matters. When expanding across borders, analyze how close or far apart the foreign market is from your own. Depending on your sector, certain dimensions may make it easier or harder for you to operate there.

Cultural Shared language, values, social norms, etc.

Administrative Trade agreements, common currency, political situation, etc.

Geographical Obvious physical distances or borders, affecting ease of transport and communication links, etc.

Economic Country resources, income levels and inequalities, infrastructure, etc.

SOURCE: World 3.0 by Pankaj Ghemawat (2011), cited in “Globalization under fire: how should leaders respond?” from IESE Insight magazine no. 35 (Q4 2017).

The CAGE Comparator tool allows users to input a country and it calculates the relative size and weight of business interactions between countries based on CAGE criteria, with the possibility of generating custom maps that are distorted accordingly.

Regardless of whether I’m doing business in Ivory Coast or in East Africa or even in the northern part of my own country (which is Muslim-majority), whenever I go to my farmers, I must always respect their culture, whether that means taking off my shoes before going inside their house or waiting for them to invite me in because they may have females inside who need to cover up. I need to first show respect to others before they will respect me and give me the social license to operate.

When setting up in Ivory Coast, I know the Nigerian accent can come across as a bit aggressive, so I need to have a team there who understands that cultural context better than I do. At the end of the day, culture is key.

DN: The Ivorian cocoa industry is facing pressure to help farmers achieve decent incomes while stopping deforestation. How can AFEX contribute to progress here?

AB: We’re starting with cocoa, because it’s important to have one staple crop and build out from there. We’re testing the culture, the model and training the people to make sure we have a strong base that we can build on.

For us, the focus is food security for the African continent, as well as bringing more value to farmers. In Nigeria, over the past 10 years, we’ve grown our rice production capacity by about four times and reduced our imports by about the same. How we evolved this ecosystem is something that I think we can also bring to Ivorian markets with cocoa.

In talking with people in the cocoa sector, people say it’s a highly regulated market with concerns about deforestation. One of the ways we can help is through geotagging, especially for high-risk export crops like cocoa, where the output from the farmer can be referenced back to the source, to make sure it is outside of deforested areas.

We also do a lot of monitoring activities on child labor, to ensure that children are getting educated and not being used as farm workers. We want children to be in school and then they can become educated farmers. Our goal is full traceability proving lack of child labor and lack of environmental hazards in the value chain.

We take all this very seriously. It’s rare to find a trading company in the global food system that is a digital native and impact focused like this. I think this makes us unique.

DN: How does this fit with your idea of Africapitalism?

AB: African culture has a unique culture of care. When you come from a place of lack, you want to share what you have and be resourceful in a way that lifts everybody up together.

“We have a form of capitalism that tries to be uplifting and impactful for everybody”

So, we have a form of capitalism that tries to be uplifting and impactful for everybody, that generates positive externalities. And it’s not charity or philanthropy. It’s doing business in a way that benefits people, and in the act of doing that business, you’re also solving societal problems and growing everyone’s incomes along the value chain.

DN: What are the most important leadership skills to create this kind of sustainable value?

AB: Resilience. Not just willpower but wait power: being able to play the long game is extremely important. And empathy. In my journey, it’s been finding that balance between empathy and execution — getting the job done, but doing it in a way that puts humanity first and treats everyone with dignity. That’s something we ensure resonates in how we deal with ourselves, how we deal with our customers, how we make decisions, and how we build products and design technology.

DN: My corporate governance research reveals unresolved tensions related to compliance with environmental regulation. How do you see this affecting farmers?

AB: A lot of times policymakers pass a law that essentially says “show me a checklist” — you basically tick a box but take no meaningful action. In the more empathetic world that I just talked about, we would have a more inclusive conversation around the problem to begin with. And we would focus on innovations that actually solve this problem, with incentives structured around the value distribution, rather than focusing on checklists, which ultimately pass more burdens onto the producers.

Farmers are already struggling; they’re the ones suffering the impact of climate change on their farmland, which is their only asset to produce value. And then you impose, say, a climate tax on him for something that isn’t even necessarily created by him. This is a conversation the world needs to have: Should we be rewarding those who can tick boxes on checklists but do nothing, or encouraging no-harm approaches to doing business, with fewer checklists?

We need more voices in these conversations. Farmers shouldn’t have to read online about policies that directly affect their income and livelihoods. They should be part of making those policies. Personally, I’m more for farmers.

READ ALSO: How Aggie Asiimwe Konde is building sustainable agricultural systems to increase incomes and boost food security for smallholder farmers in Africa.

Healthcare: Everyone wins

04Lessons from Africa for making strides in business

Ana Endres (IESE MBA 2004) is the Chief Digital Officer at Discovery Health in South Africa. Here she talks with Dr. Ben Ngoye of the Institute of Healthcare Management at Strathmore University Business School in Kenya.

In most countries, especially those with public healthcare, the problem of there being more demand than supply has been a growing concern, long before COVID-19 made the whole situation worse. Long waiting times, underfunded services, lack of access, inefficiencies in the delivery of care, rising rates of chronic conditions and the burden of disease, as well as the age-old debate over private sector involvement in the provision of a public good: these issues dominate nearly every national political discussion these days.

Discovery is no stranger to these concerns. What started in 1992 as a local insurance company has evolved to become South Africa’s largest private healthcare funder, managing around half the members in the country’s open medical schemes.

Its success in South Africa has led it to expand into other markets, not only in Africa (Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Tanzania and Zambia) but also across the Americas, the Asia-Pacific and Europe (including the U.K.), offering financial services along with car, home, business, life and other insurance products, on top of Ana Endres’ (pictured left) core area of digital health and last-mile health service delivery.

In this interview with Dr. Ben Ngoye (pictured right) of the Institute of Healthcare Management at Strathmore University Business School, the Lisbon-born Endres explains how the technology-driven assets that Discovery developed in South Africa are now being rolled out globally, including into Kenya where Ngoye is based. They aim to bring costs down and make healthcare affordable to many more people around the world, under a characteristically African vision of shared value.

Ben Ngoye: Tell us how digital tools are revolutionizing healthcare in Africa and beyond.

Ana Endres: Not long after I joined Discovery Health in 2011, I was asked to drive their new digital health project. Of course, Discovery had already been doing digital servicing, enabling people to manage their healthcare plans via a digital channel. But we were adding new capabilities, like creating the first electronic health records, which was the basis of HealthID, our interface where doctors can view all the health records of a patient online; and the first online prescription medicine delivery service, called MedXpress, expediting prescriptions for chronic conditions through a network of participating pharmacies.

BN: How does the digital channel help in encouraging healthier lifestyles?

AE: It enables us to reward good behavior. So, with our Vitality platform, the more things you do that contribute toward your health, the more rewards you get back, as your health claims will be lower in the long run. That’s the basic idea, and it’s something we’ve expanded to all our insurance products.

So, if you drive better, you get lower rates on your car insurance. If you save more, you get banking rewards. It’s always thinking in terms of shared value: it’s good for you to live a longer, healthier life; and it’s good for us, as an insurer, so we share those savings with you by giving you rewards.

BN: What are some health rewards?

AE: If we start from the standpoint of wanting people to be healthy, wanting people to be aware of their health status and regularly check it, that means they should have a health assessment every year and they should be exercising, eating healthy food, sleeping well, reducing their stress levels, and so on.

So, every time a person does any of those things, we reward them for it. It could be 25% cash back on healthy food purchases. Or special prices on meditation apps. Or up to 75% off your gym membership if you go to the gym a minimum of three times a month. There’s a broad list of rewards.

“Every time a person does healthy things, we reward them for it”

We have an entire network of partners, from food retailers to gyms. And because not everyone is a gym person, we partner with device companies, like Fitbit and Apple Watch, to offer the devices almost for free so long as people show they’re hitting their targets in terms of running or doing their steps every month.

At the moment, around half the members of our health medical scheme have activated the Vitality program and are leveraging those sorts of benefits.

BN: In what other ways are you leveraging technology?

AE: Digital allows us to constantly expand the healthcare offering in more cost-effective models and across longer distances. And it’s not just about digitizing services but it’s expanding the number of people who can access the benefits.

For example, we launched prepaid healthcare vouchers, made possible by us being able to leverage our scale as a group and negotiate better prices for a consult with a doctor, with a package of medication included. Now, anyone who doesn’t have health insurance can access this option, covering basic needs around primary care, at an affordable cost.

BN: What effect did COVID-19 have on the uptake of your digital offerings?

AE: We had been offering virtual consults before 2020, but we had some regulatory barriers that limited uptake.

In South Africa, it used to be that you could only have a virtual consult with a doctor who had previously seen you physically; so if you were healthy and at best saw a doctor once a year, then trying to set up a marketplace — matching people who wanted virtual consults only with doctors who had physically seen them before — was practically impossible.

And then COVID-19 happened and suddenly a number of those barriers were eased. Almost overnight, the uptake of virtual consults went from a few hundred a month to suddenly 10,000 a month. Patients and doctors both wanted it in order to lower their risk of COVID. We now have on-demand Virtual Urgent Care whereby, in as little as 90 seconds, you can be talking to a doctor online.

“COVID paved the way for partnerships that we hadn’t done before”

COVID paved the way for this and also for partnerships that we hadn’t done before, such as with telecom companies. With Vodacom, we offered virtual consults to all South Africans for free, including no data cost. We also partnered with the government to develop a contact tracing app.

BN: With these partnerships, what are the special considerations you need to bear in mind, especially when dealing with patient data and the need for privacy?

AE: The level of data protection depends on the type of partnership: the more data being exchanged, the higher the data protection level required.

If we partner with a digital therapeutic or a pharmacy to deliver medication — where we’re actually exchanging patient information to make the journey easy for the patient, with single sign-on and so forth — then we enforce the highest standards around data security, penetration testing, consent management and the like.

But if a partnership doesn’t require any data-sharing, then that’s a different story. With Vodacom, they were just zero-rating the virtual consult calls for us; they weren’t actually receiving any confidential patient information.

Moreover, we own the patient consent engine; we don’t leave it to partner entities to grant consent. And we always allow our members to give or revoke their consent whenever they want and for each of the different solutions.

But voluntary data-sharing is important for the benefits I talked about earlier: better clinical outcomes if the doctor can see your health history, better experience if your data is prepopulated into the third-party partner solutions, among other benefits.

BN: Do you find some groups, such as those socioeconomically worse off or the elderly, who may be more vulnerable and could benefit the most from health rewards, might also be less digitally connected or savvy? How do you deal with that challenge?

AE: We haven’t found digital to be the biggest barrier. The bigger barrier is making the offer affordable. If people find the cost too much for them to bear, then that is a barrier. So we’re constantly looking for ways to lower that barrier to the minimum it can be, while offering a high-quality product, to bring in as many people as possible.

Once people are in the app, it’s easy to track what one should be doing to improve one’s health, and we have health coaches and other supports to help people understand these programs better and work with them to change their behaviors, using engaging gamification.

BN: How are you using AI in this process?

AE: We’re currently piloting a generative AI-supported coaching platform. And it has been incredible to see a good percentage of people over 65, or 80 even, engaging with the generative AI chatbot.

So, we had a cohort of diabetics or people who were at risk of becoming diabetics (which we could detect through their annual health assessments). And we offered them sessions with a health coach — these are virtual touchpoints but with a real coach, with the app nudging members every day and allowing both parties to chat back and forth.

The power of the generative AI is in laying out potential responses that the coach can then adapt and edit, as well as creating continuous and context-aware engagement with the member. And the system is constantly learning from the engagement. The coach then becomes much more effective and efficient in being able to answer right back and creating continuous contact.

The use of AI in this way has really transformed engagement: we’ve seen 84% engagement rates in our pilot so far.

BN: Discovery has been operating in South Africa for over 30 years. What made it start expanding into the rest of Africa in 2022?

AE: We had been pondering expansion into the rest of Africa for a long time, but there were always reasons for not starting then — either a lack of industry maturity, or specific opportunities outside of Africa that were demanding a lot of attention.

At the beginning of 2021, it was decided that the time was right to expand to the rest of Africa, and in January 2022 we went live with the first health insurance product.

“We see so much potential in the rest of Africa. We’re just touching the tip of the iceberg”

When choosing which countries to expand to, there must be a certain number of things in place for a market to be of interest.

For instance, it has to be large enough, with a significant concentration of local, reputable employers for us to partner with, as we were initially offering our health insurance products to corporates, not individuals. There also needs to be a mature network of private healthcare doctors and services. The regulatory environment has to be supportive for us to get a license to operate. All these things need to be in place.

Two years on, we are now present in seven other African countries. We see so much potential in the rest of Africa. We’re just touching the tip of the iceberg.

BN: What were some of the challenges?

AE: Data availability for starters. There was little to no data for us to properly estimate the likely claiming patterns in those countries. So, we had to go with certain assumptions. After a few months post-launch of seeing real data, we could understand how many of our assumptions were correct or not, and then reprice our product based on the real data.

We also had some learnings around doctor and healthcare provision networks, specifically the depth of the network required to meet the local expectations.

BN: As your business model relies so much on digital, did you find digital penetration to be an issue?

AE: It varies from country to country. Some countries are much more mature than others when it comes to digital solutions.

Kenya has got outstanding tech. For instance, they have sophisticated solutions to combat card fraud (such as when people give their own medical aid card to someone else who fraudulently uses it). It was easy to find a partner with a ready-packaged digital solution for handling those sorts of issues.

That wasn’t the case in every country. We come with state-of-the-art devices that can, say, read your cholesterol from a blood drop from your finger and automatically upload the data to the cloud. And in some countries, people wouldn’t trust the quality of this health test unless the blood was drawn from veins and analyzed the traditional way.

BN: Prior to Discovery, you worked for U.S. multinationals, including Johnson & Johnson. What are your reflections on the U.S. healthcare market?

AE: We see great healthcare innovation happening in the U.S., but overall healthcare there is extremely expensive and just keeps on getting more expensive. In terms of data-sharing and for interoperability to become commonplace, it doesn’t seem like the rate of return has been commensurate with the huge amount of money they’re spending. It’s a super fragmented market with very little joined up.

“We see how all individuals, doing this together, benefit society. We are all healthier together”

The difference we have in South Africa is that Discovery Health captures half the market. This means we’ve got scale, and with that comes the power to negotiate things that would be unusual in other countries.

We also have two key digital assets: the apps, via which we engage with members directly on what they need to be doing to improve their health, and the doctor interfaces, where doctors see their entire population of patients on health management dashboards and, at the press of a button, can nudge a patient in certain directions. Having these two assets, joined together, talking with each other, is very powerful.

I’ll give you an example on mental health, which has been a big problem since COVID. We nudge the member to fill in a mental health assessment and we give them points for doing so. The results are shared with the member for awareness, and we suggest whether they should book a visit with their GP. The results are also shared with the doctor, indicating if the member has booked a consult, and the doctor is able to prescribe digital therapeutics for mental health, such as one called SilverCloud on our platform. The engagement metrics, and the results on how the member is improving or not, are then shared with the doctor.

These kinds of journeys are, I think, quite important to ensure that the care isn’t fragmented. It’s part of our secret sauce.

In addition, the private health sector has created a health information exchange at the country level, where patients have given their permission for data to be shared. This gives everyone a better view across the board.

All these factors, developed over time, have created the picture you see today.

BN: Can you talk a bit more about this idea of shared value? It’s a bit of a buzzword but seems to mean something special in the African context.

AE: There’s the individual sharing of value: what you, as an individual, are doing for your health and, as a result, you get rewards. And for some it stops there. But we see how all individuals, doing this together, benefit society overall, and we want to drive this pathway for positive change at scale.

We work every day to strengthen the healthcare system and expand access to care for all South Africans. We are all healthier together, and the overall health costs decrease for everyone. There are societal impacts over and above the individual impact.

Perhaps there is more of an awareness of that here in Africa. Traditionally, Africans have found private sector healthcare products out of reach because they were too expensive. Here we have an interest in expanding the group of people accessing these kinds of products and services.

It’s about making world-class healthcare cost-effective and available to as many people as possible. Everyone wins in the end.

Retail: Busting myths, bringing joy

05Lessons from Africa for making strides in business

Guy Futi is Co-founder & CEO of Orda Africa. Uchenna Uzo is a Professor of Marketing at Lagos Business School in Nigeria. Read his insights on African retail at Afritail.

Born in Gabon to parents from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guy Futi (pictured left) grew up in Canada where he earned his bachelor’s degree at Concordia University, Quebec. Then, he did a master’s at Harvard and is currently working on his doctoral thesis for Oxford University on social entrepreneurship, a topic close to his heart, having previously worked for Maji Water on sustainable water solutions in Africa. He also worked for Jumia, the first African e-commerce company to list on the New York Stock Exchange, dubbed “the Amazon of Africa.”

Today, he resides in Lagos, Nigeria, a focal point of his thesis and where he recently launched Orda, a cloud-based platform allowing food merchants to process orders, accept payments, connect to logistics providers, engage with customers — basically, to do everything a food business needs to run its operations from anywhere on the continent.

Lagos Business School professor Uchenna Uzo (pictured right) was interested in Futi’s perceptions of Africa’s informal markets, a subject on which Uzo has done extensive research. In this interview, they discuss the myths and identify success drivers related to African retail and consumer behavior — especially important as Orda has entered Kenya and is testing out the South African and Moroccan markets, as Futi’s vision is for Orda to become a truly pan-African enterprise.

Uchenna Uzo: It’s beautiful to see how your business is growing in such a short span of time, which suggests there’s a great opportunity to scale. What do you see that makes consumer food retail a growing domain?

Guy Futi: When looking at expansion, we’re looking at restaurants. Around half our clients are restaurant owners, with the majority of them still running their businesses with pen and paper. Our goal is to use technology to unleash the power of the African food business owner.

We also see a burgeoning middle class and a youthful population. The first thing people think about when improving their lives is improving the quality of the food they eat. People are always going to want to eat, and eating out is one of the last things people want to sacrifice. Despite what’s going on in the macro, those are promising indicators for a business like ours.

UU: 60% of the average Nigerian spend goes to food these days. So if you’re in the food business, that’s definitely a promising area. Another thing is that a lot of food businesses buy in informal settings — the open market stalls and shops. How does that impact your business?

GF: We started off with street food stalls called bukas or mama puts. They know what restaurant software is; they’ve seen it at places like KFC, but either they believed it was out of reach or no one had explained the benefits to them of how it could improve their day-to-day operations.

We spent one to two years educating that swath of the population about how this was going to improve their business. They might spend hours figuring out how much they earned that day, based on a bunch of receipts or guesstimating the number of dishes sold. That leaves a lot of room for leakage. And they’re dealing with cash, cards, inventory, staff, rent, supply chains. It’s very difficult to manage all this with just a pen and paper receipts. So, a big part of our journey was to get these merchants to go from analog to digital. And those who are using Orda are now our biggest advocates.

UU: 70% of the sub-Saharan African workforce operates in these informal market settings and 90% of retail transactions pass through informal channels. Yet many multinationals operating outside Africa express doubts about these markets, thinking they’re a no-go area for investment. What do you say?

GF: I’d question how anyone could ignore 70% of an economy! I’d even go further to question how an online payment processor like Stripe operating out of the U.S., for example, can have roughly the same valuation as the GDP of a country like Congo: So you’re telling me that one company is worth more than all the resources, minerals and brain power of an entire nation of 100 million people? I challenge that.

What you see on the surface does not fully represent the true value of what is really happening on the ground. If you say you can’t build a proper business until it joins the formal economy, then you’re going to find yourself waiting a very long time, losing out on opportunities and later finding yourself having to catch up. Better to find a way to tap into the informal economy and make it a part of your mission from day one.

3 market myths

Uchenna Uzo has researched Africa’s informal markets, including Nollywood, Nigeria’s movie industry; surveyed 1,100 street shoppers as well as surveyed MNCs using informal distribution channels; and did an ethnographic study of informal retailers representing five industries, involving 113 observations of negotiation procedures.

These are the common misconceptions that turned up:

Myth 1: Illegality Informal markets are illegal ones

Myth 2: Discontinuity Informal markets must modernize or die

Myth 3: Irrationality There’s no structure to informal markets

UU: I’ve spent more than 10 years looking at different aspects of informal markets, which led me to start the Africa Retail Academy at Lagos Business School. And we’ve identified three common reasons people give for not wanting to invest in informal markets. I’d like to get your opinion on these. First, people say they are illegal — that “informal” implies breaking the law.

GF: People need to understand a few things. When trying to set up a business anywhere in the world — whether Singapore, the U.K. or the U.S. — the information has to flow, with transparency and clarity about how to get things done.

In some places, like Nigeria, when you want to start a business, it’s more opaque and blurry. If I want to set up a stall, I don’t know what I’m supposed to do or what licenses I’m supposed to get, because no one has told me. And without that license, I’m technically operating illegally, but it’s not intentional, it’s just sometimes very difficult to find the right information.

At the end of the day, people want to work and make money. And they don’t want to deal with things that obstruct that. I think that if the information were clear, transparent and easier to obtain, people would know how to structure their businesses and do so. This is what we’re trying to do with Orda.

UU: The second claim is that these markets will die unless they modernize or formalize.

GF: Never. The informal market will be here forever. Even in more advanced or higher GDP countries, you still see people with street stalls. I think they’ll remain a fabric of all our societies. And why would we want them to go away anyway? What we need to do is make sure they have the right information and the right tools to grow, and then figure out how they can contribute more to the economy through taxes, for example.

UU: Third is that informal markets are completely unstructured.

GF: Certainly these markets are fluid and their practices aren’t always codified. But they do have “structure” in the form of trust and social capital, which, as Francis Fukuyama famously said, is key for the economic prosperity of any society.

Commerce is essentially trust at its very core. When people buy something, they want a secure method of payment; they want to make sure that when they enter into contracts, there are repercussions for breaking them; that if someone defaults, they’re going to get their money back; that there are checks and balances that foster an environment where people feel safe to do business together. This requires trust, which underpins even informal markets.

UU: It’s true, Africa’s informal markets have far more structure and self-governance than many people think. It’s misleading to think otherwise.

MICE framework: 4 keys for business success

M Master the art of negotiation and cultural awareness

I Invest in talent

C Change your mindset

E Earn the market’s trust

UU: Let me ask you about a framework we’ve developed called MICE. Each letter stands for a key pillar that can help international businesses succeed in Africa. E stands for Earn the market’s trust, which you’ve just discussed. Let’s look at the other pillars, starting with M, Mastering the art of negotiation and cultural awareness. How important is this to your business?

GF: Negotiation as relates to culture is extremely important, not just in a pan-African context, but I would say in the Nigerian context alone. A market in Abuja doesn’t operate the same way that a market in Lagos Island would operate. The velocity of transactions and decision-making in Lagos Island is breathtaking. Whereas if you go somewhere in the north, things take time. You have tea, a conversation, a bit of bartering, and the people are more familiar with each other — trust matters here. The way my salespeople sell software in Lagos is completely different from how they would in Abuja.

In Kenya, I would say the sales cycle is longer, trust takes longer to build. Recommendations and referrals come at a premium, whereas in Lagos the right price is dictating more. So, understanding the local cultural dynamics of the markets where you’re operating is essential for success.

UU: What about Investing in talent? What’s your experience with talent development in order to grow business in this space?

GF: Investing in talent is crucial. In our market, the opportunities are so wide, you have to make the most of your talent while you have them, because they’re going to leave eventually — it’s not a matter of if but when. Africa is the perfect environment for someone with ambition, intelligence and drive, someone who is a real self-starter. And if you can make the most of that talent, even for two or three years, your business is winning.

UU: C is about Changing your mindset. We talk about entrepreneurial reframing — turning every challenge into an opportunity, choosing a different approach to tackle a problem. Does this resonate with you?

GF: An investor once told me that entrepreneurs have a screw loose. And I do think I may have a couple of screws loose! Everything is an opportunity. There are no problems, just the right solution hasn’t been found yet. I think most of us want to get something done, and we’ve been told it’s either difficult or impossible. But the fact that it’s hard is the fun part — that’s the joy!

I can’t tell you the number of times people have asked me if people in the informal economy really want to pay for software. Well, yes, they do, but maybe not in the way you’re looking at it, and it’s up to you to figure out how to monetize it.

I was in Congo recently and people were saying there were fewer than two million debit or credit cards issued in a country of 100 million people, as if that limited the opportunities to be had there. And I was like, “Are you kidding me? Whoever is able to get the other 98% of the population bank cards — even just banking 1% of that unbanked population — is going to be wildly successful!” I was thinking I’m too busy with my own company, but here is another amazing opportunity.

“Knowing I’m contributing to a crucial sector of our economy is the part that I love”

UU: Finally, people talk about Africapitalism — a more inclusive form of capitalism which is about profit with purpose, using private enterprise to transform the continent by uplifting the communities in which they operate. Does this inform your business vision at all?

GF: I don’t know if I would use the term Africapitalism to describe what I’m doing. Let me express it this way: There are two things that bring me great joy.

The first is seeing our product out in the market and how it is transforming the way people run their businesses. I love going somewhere and asking about Orda and people say, “Oh, I used to lose so much time and money and now I’m saving both.” It’s knowing that I’m contributing to a crucial sector of our economy. That’s the part of being a business owner/operator that I love.

The second thing that brings me great joy is seeing the people I’ve worked with and mentored going on to start something else, building their own businesses that are adding even more value. Sometimes they ask me for support, and I help out where I can. In this way, we’re collectively changing an ecosystem and empowering the next crop of entrepreneurs.

I think that’s very important. When you’ve been privileged enough to be in a position to lead, to have this sort of input and make an impact, then we all owe that responsibility. That’s how I would describe it.

Banking with HEART

06Lessons from Africa for making strides in business

Abubakar Suleiman is CEO of Sterling Bank in Nigeria and an alumnus of the IESE Global CEO Program. Clinton Ofoedu earned his PhD at IESE.

Sterling Bank has been named the most innovative bank in Nigeria. Although it may not be the biggest bank by assets, CEO Abubakar Suleiman (pictured left) is determined to make it the most disruptive and socially responsible, through an inclusive growth strategy based on five pillars: Health, Education, Agriculture, Renewable Energy and Transportation, or HEART for short.

For Clinton Ofoedu (pictured right), who researches entrepreneurial growth and sustainable development in emerging economies, Sterling is a fascinating case. In collaboration with IESE entrepreneurship professor M. Julia Prats, Ofoedu has been conducting a series of interviews with Sterling executives, partly to explore the influence of technological innovation on firm performance — the focus of his doctoral research.

Here he teases out the winning ingredients of Sterling’s transformation, in which fintech plays a role. Having a corporate purpose beyond profitability, of finding sustainable and economically viable solutions for solving social problems, is what drives the bank’s efforts.

Clinton Ofoedu: Banks are traditionally not known for being the most innovative or creative, and the sector is highly regulated. How have you managed to experiment within the confines of this space?

Abubakar Suleiman: Financial institutions are primarily designed to respond to the regulator, with the customer second. We wanted to change that. To innovate, we knew we had to take the process out of the traditional banking ecosystem where experimentation generally isn’t encouraged.

We started by breaking down our organization, removing the hierarchy, to allow what we call situational leadership — that is, irrespective of your rank, the person who is interacting with the customer makes the call.

We hired new kinds of people who were open to innovation. And when we brought them in, we created spaces for them where their success wouldn’t be judged by how profitable they were at growing financial services. Instead, we introduced a separate R&D budget that wasn’t tied to P&L and could be written off at the end of the year.

We also created an entrepreneurs-in-residence program, to create a pipeline of young talent who, if we liked their ideas, could continue to work for us and become part owner of the project they helped create.

CO: Can you explain your HEART strategy decision?

AS: In Nigeria, the banking system is highly concentrated, with almost two-thirds of the industry controlled by a handful of banks. When I became CEO in 2018, the question I asked myself was: How do we take those banks on?

When a sector is oligopolistic, it’s extremely difficult to compete in that space. As such, if growth in financial services wasn’t going to be the center of our strategy, what was?

Often, financial services are the last leg of a prior sequence of economic activities. But if the prior infrastructure that eventually leads to financial services isn’t there (as is the case in many emerging markets), then what could we do?

Rather than waiting at the bottom of the hill for the water to flow down, competing with those who have much larger balance sheets than us, we thought: Why not go to the top of the hill and address upstream challenges instead?

In deciding on Health, Education, Agriculture, Renewable Energy and Transportation (HEART) as the challenges that we, as a bank, would address, we sought sectors with massive growth potential — where there was huge demand but supply was weak or missing.

We also chose sectors that accounted for a significant part of the country’s GDP, so that, if we baked banking into those sectors, people would come across us one way or another.

“We wanted impact sectors that would be long-term profitable”

Additionally, we went for sectors where the growth was sustainable. There are many different sectors of impact, but some are only profitable in the short term — you can’t keep scaling in perpetuity because there’s no further need to be met. We wanted impact sectors that would be long-term profitable.

CO: How do the strategy and innovation teams work?

AS: It requires internal and external scanning of the environment, with the strategy team connected to the innovation team, because we don’t want a gap between strategy and implementation. At our annual retreats, we identify critical things that we think need to be fixed in order for us to create value. Then, we give the innovation team a budget to figure out what needs to be done and test out potential solutions.

For instance, we noted a gap between public and private education, with private schools outperforming the government options available in certain communities. So, we gave it to the strategy and innovation teams, and they came up with a financial product to enable access to high-quality private schools in low-income communities. That product won a community banking award.

CO: In addition to changing the culture and mindset of the bank, Sterling has been active in the fintech space. What are some innovative products that have made an impact?

AS: Digitalization has been key to our transformation. Digitalization is not just about how much technology you buy in; it’s the extent to which you innovate with the technology internally.

One of the most successful products we built was an automated credit lending platform called Specta. Credit decisions used to take up to six weeks; now we can make a credit decision in as little as five minutes. We’ve gone from lending N5billion to N106 billion, with lower non-repayment rates than before. The more individuals who use the platform, the more our AI algorithms learn from customers, offering a better and better service.

This led to the creation of another platform called Imperium. Once we establish the credit is good, we can connect customers with renewable energy providers and help finance the installation of solar panels, which in turn addresses the country’s energy crisis.

“It’s thinking holistically about all the ways that banking fulfills an individual need but also a social one”

It’s thinking holistically, like this, about all the ways that banking fulfills an individual financing need while at the same time connecting consumers with a solution in Health, Education, Agriculture, Renewable Energy or Transportation, thereby stimulating economic growth, at the micro and macro levels.

CO: At IESE we research corporate venturing: traditional firms learning from, investing in and partnering with startups to boost their own innovation. What’s your view on this practice?

AS: The standard corporate view is that the startup is out to disrupt them, so the incumbent does everything possible to frustrate the startup. They come from the perspective of the fixed pie, with everybody fighting over their piece. Banks approach fintech startups from a position of fear: What will they do to us?

I, on the other hand, want to be part of the process and have a constructive relationship with startups. As a bank, there are some things we’re better at, such as managing the regulatory side of things, because that’s what we have to do and have experience doing.

Many startups find themselves running into regulatory headwinds and realize they need to have a relationship with us, too. So we can work as partners. They get the benefit of the established banking business, with us taking on the R&D costs, and we reap the benefit of their innovation.

For example, through partnering with Founder Institute, we collaborated on Cafe One, a coffee shop and coworking space that supports SMEs. After talking to many SME founders, we decided to set up a venture fund to invest in SMEs, recognizing that some of the best innovations are not going to happen solely through us but depend on the existence of a wider entrepreneurial ecosystem.

It’s important for us to invest in external innovation that affects our core HEART strategy. By doing so, we accelerate development in those sectors, and end up banking the new businesses in those spaces.

This is the thinking for us: How do we enable external innovation that will eventually allow us to embed banking in the ecosystem?

CO: It is well-documented that regulation will condition a firm’s innovation activities, for better or worse. How have you navigated this?

AS: A central bank director made an eye-opening comment: “We don’t regulate technology.” By this, he meant it’s the risks associated with your product that require regulation: Is the technology secure? Does it meet certain standards? Are the customers protected? That’s an important distinction, which informs how we go about investing in technology.

“The key is to find the nexus between impact and business”

We also try to be innovative in areas where the government is looking for help or support. It was during the COVID-19 pandemic when we really won the heart of the regulator. As healthcare financing was one of our HEART pillars, we immediately understood there were going to be challenges that the government might not be prepared for. So, we assembled our health tech partners and built a platform to verify proof of vaccination for safe travel, initially for the Lagos state government but eventually the rest of the country signed up to it.

That kind of community service, working with the regulators rather than trying to get around them, made people more open to what else we could offer.

CO: In Africa, as in many other parts of the world, firms are facing a war for talent, as young, highly qualified, in-demand professionals are being lured to work elsewhere. You talked about the need to bring in fresh profiles to help drive your innovation efforts. How do you avoid brain drain and attract the right talent you need to be successful?

AS: The key is to find the nexus between impact and business. A lot of young people are impact-focused; many want to go work for NGOs. Our job is to convince them that they can have as much of an impact, if not more of an impact, working for us as working for the United Nations.

We don’t need a lot of money to have an impact and get returns on our investments, which in turn attracts even more investments. People see that, and they may be willing to earn less money knowing they are working on something bigger than “just doing a job.” I have executive directors working for me who have turned down the chance to be CEOs of other companies.

We have found a common purpose that we — our bank staff and stakeholders — all deeply care about. We offer our employees shares in the bank, so in addition to their pay, they become equity holders. We are also trying to build a larger campus to train the next generation, developing a pool of talent larger than what we currently need. In this way, we make sure to retain enough talent to keep our business going.

CO: What is your perspective on the role of the private sector in promoting inclusive growth in Africa?

AS: One of our core values is “the success of one is the success of all,” and in many ways that encapsulates our business philosophy. It means that if you’re lucky enough to hold a senior role in a significant company in Africa, you have an obligation beyond making money, which is to make a positive impact. And that impact isn’t just about one company; it’s about the society we live in and what we can do for it.