Global uncertainty: business solutions for a fractured world

01Global uncertainty

The big idea of the 20th century is under fire in the 21st. How to respond with foresight, intelligence and, above all, empathy.

Today is the slowest day of the rest of your life. That’s the maxim that Nokia board chair Risto Siilasmaa lives by. “You probably thought that the pace of change has never been as fast as it is today,” he told a crowd gathered in New York City for IESE’s Global Alumni Reunion. “But you’re thinking about it the wrong way. Change will never be as slow as it is today. If you think about it this way, you have more of a feeling that, ‘I need to act right now, and if I don’t act today, it’ll be more difficult tomorrow.’ That’s the only way to navigate in this world.”

Taking decisive action is key to surviving today’s geopolitical turbulence

Siilasmaa should know. He joined Nokia in 2008 when the company was at its peak and by 2012 “the press was speculating about the timing of our bankruptcy. Not if, but when.”

“It’s easy to say that Nokia was caught by surprise, but that’s not true,” Siilasmaa insists, noting that Nokia “was very early with all the technologies that ended up disrupting us. We can’t say we didn’t foresee all this. We did; we just didn’t act.”

Taking decisive action is one of the keys to surviving today’s geopolitical turbulence. And it’s not just technological innovation and shifting consumer demand that are driving this turbulence. All around the world we see widening inequality, soaring public debt, tightening liquidity and threats of an all-out global trade war. The United States under President Trump seems bent on upending the status quo by withdrawing from or renegotiating international trade deals, imposing tariffs and adopting protectionist stances in pursuit of an unapologetically nationalist agenda.

In this report, we draw upon the research of IESE professors and the real-life experiences of three top executives from leading companies around the world to suggest some of the ways that business people can act fast – but also coolly and wisely – in a world that is changing, as Siilasmaa puts it, “in more complicated and unpredictable directions.”

Building, developing, learning

What gets you out of bed in the morning? For Laxman Narasimhan, CEO of PepsiCo Latin America and Europe Sub-Saharan Africa, it’s the story of a Guatemalan farmer who he says told him, “I want to thank you for the fact that you help us grow potatoes here and you buy from us. What this does for me is that it prevents my son and his children from trying to migrate elsewhere. He can stay here and make a living.”

Narasimhan adds, “When you hear stories like that, you realize the privilege of the platform you have as a business leader. You can make a big difference in the lives of others.”

Guatemala serves as PepsiCo’s regional hub, where roughly half of the 6,000-plus people that PepsiCo employs in Central America are based. As PepsiCo’s Daniel Moisan told a Guatemalan newspaper recently, “You always have to think about the long term.” If you only manage thinking about what may be expedient in the short term, “in the end that may take you to a place you don’t want to go. With the long term, there’s no conflict between the social agenda and the business agenda. We have to think more about what’s coming, about what’s best for the future.”

Such thinking reveals an alternative way of tackling perceived global problems. You can either retreat, or you can follow Narasimhan’s stated motto of “building, developing and learning,” which he explains means embracing new opportunities; recognizing the impact of your actions on others and taking that responsibility seriously; and improving yourself by, for example, learning another language, such as Spanish, as Narasimhan has committed himself to doing. In short, “it’s the experience of being out there and observing what’s happening in the world.”

What effect could Brexit have on investment?

While it may take a few years for the real impact of Brexit to reveal its true effect, the 2018 Venture Capital and Private Equity Country Attractiveness Index (prepared by Alexander Groh, Karsten Lieser, Markus Biesinger and IESE professor Heinrich Liechtenstein) predicted that the attractiveness of the U.K. for venture capital and private equity investors would likely take a hit. Assuming U.K. GDP growth of 1 percent below what it would be without Brexit, a 20 percent haircut on U.K. capital market depth, and a 2 percent increase in U.K. unemployment compared with what it would be without Brexit, the U.K. dropped four positions, to 6th from 2nd place. Admittedly, the U.K. could adopt measures to improve investment conditions between now and its official withdrawal from the EU. Still, a future loss of position seems inevitable.

Beware the globaloney

In observing, make sure you get your facts right. This is a point that IESE’s Pankaj Ghemawat has repeatedly stressed. “Don’t let the debate about globalization turn into guesswork. Study the data,” he writes. “Much of the rhetoric around globalization has been hyperbolic, so the reactions we are now seeing need to be put into proper perspective. Before jumping on the bandwagon and pulling up the drawbridge, business leaders should make sure they have an accurate picture of what’s actually happening in the world today.”

In his article “Globalization Under Fire: How Should Leaders Respond?” Ghemawat presents convincing evidence that many of the claims on which leaders are basing some drastic decisions – from restricting immigration to repatriating business activities – are simply unfounded, or what he calls “globaloney.” The ills of globalization were never as bad as some people made them out to be. And certain immutable “laws of globalization,” such as two countries sharing a common culture, language or border, will continue to be decisive factors that condition international business activity, regardless of the politics of the day.

Many of the claims on which leaders are basing some drastic decisions are unfounded

Citing data he previously helped collect for the DHL Global Connectedness Index, Ghemawat writes: “It seems odd to blame globalization for the high levels of inequality in the U.S. economy. Compare the U.S. with the Netherlands, the most globally connected country according to our index. The Netherlands has a trade-to-GDP ratio six times that of the U.S., yet the Dutch still manage to preserve a more reasonable income distribution. What’s going on? I’d say that domestic policy is the primary driver of distributional outcomes within countries. And even if globalization were to blame, it doesn’t follow that protectionism would be a better or less expensive solution to address economic inequality.”

This is not to say that income inequality isn’t real or that business leaders don’t have to pay attention to the anger that’s feeding anti-globalization sentiment. “A large swath of the population in advanced economies fears getting left behind. At the same time, corporate profits are running at historic highs. Clearly there are some distributional issues that need to be fixed. This requires policy changes related to government safety nets, the minimum wage, taxation and job retraining programs.”

However, Ghemawat adds, “Closing borders does nothing to prepare a country to deal with automation and technological progress, which are the bigger threats to jobs than globalization. My research suggests that more international openness, connectedness and integration, coupled with domestic policies that remedy the side effects, would lead to more prosperity and well-being overall.”

A blend of global and local

On a practical, managerial level, much of what we see and discuss as globalization isn’t, strictly speaking. “A lot of what we see today is really a blend of global and local,” says PepsiCo’s Narasimhan. “At the end of the day, we are local players in 200 countries around the world. So, we need that local face. We need to be Nigerian in Nigeria, Kenyan in Kenya, Peruvian in Peru, Brazilian in Brazil. We really have to find a way for us to ensure that we represent not just global but also local, which requires getting very deep in terms of what we need in that country.”

In this regard, Narasimhan seems to be describing one of three time-tested strategies identified by Ghemawat for a global company to boost revenue and market share: adaptation of your products and services to local tastes and needs. (Aggregation and arbitrage are two other strategies.)

“In order for us to compete in a place like China,” Narasimhan explains, “first we have great Chinese talent that powers our business, but also local partners who help us work through local ecosystems to be relevant in the many Chinese sub-geographies beyond Shanghai and Beijing. Consumers do like strong global brands that communicate quality but you can’t just be a ‘global’ global brand. Some of our advertising is extremely Chinese and appeals to the Chinese consumer in ways that are very relevant to their culture and how they live.”

“You’ve got to find that appropriate balance (between local and global),” he stresses. “This is certainly one of the big things we’re keeping our eye on.”

A global strategy framework

According to Pankaj Ghemawat, the right strategy is often a mix of three strategies, depending on industry conditions, competitive factors, firm capabilities and organizational structure.

Adaptation Create value by changing your offer according to local requirements or preferences.

Aggregation Achieve economies of scale or scope by creating regional or global efficiencies; e.g., standardizing a portion of the value proposition, or grouping together development and production processes.

Arbitrage Exploit the differences between national or regional markets; e.g., leveraging lower labor costs or better tax incentives in one country versus another, as is done through outsourcing or offshoring.

As the Executive Board member responsible for SAP’s Global Customer Operations in Europe, Africa, Middle East and China, Adaire Fox-Martin describes how SAP structures things both locally and globally. “It’s important that each geography predominantly features local talent. The team must reflect the community they serve. That team needs to take an element of corporate strategy and then decide how to localize the corporate priorities in a locally relevant context.”

But it’s not just what happens at the local level: “People also want to understand what their peers across geographies are doing to streamline business, digitalize a process or transform customer engagement.”

This is where the cross-pollination or aggregation of know-how “really adds value for everybody,” Fox-Martin believes. “The global sharing process and the thought leadership that we bring in speak to what our customers would like to learn from us. We always do it in a context of the jurisdiction in which we operate. Even though global, for SAP deep local relevancy is imperative.”

Scenario planning

Having this deep (local) and wide (global) expertise is vital for detecting signals in the market that might have major ramifications for your business. IESE’s Mike Rosenberg has written extensively about this aspect in his book, Strategy and Geopolitics: Understanding Global Complexity in a Turbulent World. Ever since the ’80s when companies began adopting lean approaches to inventory management to boost efficiency and reduce waste, a just-in-time logic has taken hold across many areas of management. At times this logic may manifest itself in less helpful ways: a short-term bias in managerial decision-making, quarterly capitalism, reduced CEO tenures, and the reduction or elimination of country-level managers, and with that, the loss of invaluable local market insights. Consequently, today’s geopolitical climate – where global supply chains and freedom of movement are suddenly being disrupted – may come as a shock to the system.

To minimize the fallout, traditional strategic planning is not enough, Rosenberg says. All too often, strategy development is reduced to an annual exercise dictated by urgent operational concerns. Or it might get outsourced to a consulting firm, whose recommendations are treated as additional “food for thought” on top of a strategic direction already decided. Frequently missing is any profound reflection on management’s and the board’s assumptions about the current state and future direction of the world.

Managing in the midst of global uncertainty

In addition to being a paranoid optimist, Risto Siilasmaa offers these tips for managing in today’s climate…

Beware of the toxicity of success Be careful if you start to focus on secondary topics rather than the core of your competitiveness. What are your greatest assets? What are your customers thinking? Spending less time on those topics should be a red flag.

Always have alternatives If you only have one plan, nobody wants to give you bad news about it, because then you’ll have nothing left. But if you have five plans, it’s only one of five.

Think long term Don’t fall into the trap of just putting out fires. Stop to think, what does this mean? What are the actual big things that I should be worried about?

Try to measure it Metrics and KPIs create a common vocabulary, so you can talk about the issues openly.

Don’t be captive to roles Can the CEO be challenged? It’s so important to be able to challenge everybody, with respect, in a trusting environment.

As such, Rosenberg recommends scenario planning – not to be confused with forecasting. “Forecasting can be an outstanding tool for projecting demand in relatively stable environments,” he says. “But when it comes to strategic planning, forecasting is woefully lacking. For proof, look no further than the failure of the business community to foresee Brexit or Trump’s election.”

Siilasmaa describes how scenario planning helped the board bring Nokia back from the brink of bankruptcy: “On the old board, if we saw the future as a dark, unknown landscape, we’d look for one well-lit path and that would become the official plan. But when that plan failed time after time, we realized that the well-lit path was the one not to follow – we’d have to go outside the path. With scenario planning, we identified various ways that we could go forward; the dark landscape was crisscrossed by several paths. And even if we didn’t walk down any of those paths exactly, we could go close to some of them and see what the terrain was like. It meant thinking and talking about the worst outcomes, and preparing for them.”

He calls this “paranoid optimism” – which forms part of the title of his new book on Transforming Nokia: The Power of Paranoid Optimism to Lead Through Colossal Change. In it, he details the company’s remarkable reinvention as a leading player in the global wireless market.

“Paranoia actually creates a reason to be optimistic,” he explains. “Whenever you’re making a major decision, you should always appoint a Red Team or a Cassandra who has the right to say negative things and the duty to find the holes in the logic. It’s a good practice. At the same time, because you’re taking actions to preempt and prevent the worst outcomes, you can be optimistic that you’ll achieve some good outcomes.”

Doing this is also a good means of making sure that bad news reaches the right ears. One of the problems at Nokia, he explains, “was that bad news didn’t flow to the top. People were afraid to deliver bad news. The top management didn’t know where the fires were burning or whether there were any fires at all. And the board definitely didn’t know.”

Global talent by numbers

AXA surveyed employers in eight countries on the need for a globally mobile workforce. The conclusion? More, not less, globally proficient talent is needed.

63% saw it as important

35% saw it as critical

Meanwhile, the desire to work abroad has fallen from 64% in 2014 to 57% in 2018, according to a Boston Consulting Group survey of 366,000 workers in 197 countries.

11% decline in those willing to go abroad

Siilasmaa adheres to this new twist on an old refrain: “No news is bad news, bad news is good news, and good news is no news.” He unpacks what this means: “No news is the worst kind: you’re shut out. And bad news is actually good news, so when somebody comes to you with bad news, be careful that you don’t let your frustrations show, because next time that person may think twice before telling you. Instead say, ‘Thank you for coming to me. Now we can think about what to do.’ And if you’re doing things right and getting good results, that really shouldn’t be news at all.”

Culturally intelligent leaders

“To build and manage global supply chains capable of weathering even the most turbulent geopolitical storms, companies need to take big steps in their people management,” says Rosenberg. In particular, it’s about recruiting, training and developing people with different backgrounds, not just those with the requisite business skills but also people with liberal arts backgrounds, versed in history, political science or Asian and Middle Eastern studies, for example.

Ghemawat writes: “Firms should strive to cultivate a cosmopolitan corporate culture that can serve as connective tissue across a far-flung corporation. Partly it’s about formal culture-building activities, but it’s also about how you recruit, assemble teams, manage diversity internally, support specific initiatives and side projects, and encourage mobility (not just in terms of jobs, but traveling, living and working abroad). Education is a lever for boosting cosmopolitanism both at the corporate and the societal levels. Multiple studies have shown that levels of nationalism and suspicion of outsiders are higher the lower the levels of education in a country. Given this, it makes sense to delve into educational content that can support a more cosmopolitan outlook.”

The more divided the world becomes, the more we need culturally and emotionally intelligent business leaders able to build bridges of understanding. B. Sebastian Reiche, head of the Managing People in Organizations Department at IESE, has researched and written about the need for more culturally sensitive leaders able to navigate the complexities of our increasingly polarized world.

SAP’s Fox-Martin is a good example. Originally from Dublin, she began her career in London before moving to Australia. She worked for nearly two decades in Asia before moving to Germany in 2017 to take up her current role. “These cross-cultural experiences give you a completely different lens,” she says.

“There might be things that you don’t like about country A, B or C, but it’s important to focus on the positive elements of each society. I’ve always adopted a position of being very observant, listening more than I would speak and trying to understand the nuances. Because if there’s an implementation of a strategy that you want to drive globally, you have to be culturally aware and a lot more sensitive to understanding the local elements that are essential to making that strategy effective in given markets.”

The more divided the world becomes, the more we need culturally and emotionally intelligent business leaders able to build bridges of understanding

Leading in the world today, perhaps more than ever, requires a high degree of empathy. “I think an empathetic approach is essential,” says Fox-Martin, “to be able to put yourself, not just in your customer’s shoes, but in the shoes of your customer’s customer, and understand how that person is experiencing the business. And then, based on that experience, bring insights into your conversations with the customer as a way of helping them achieve a better outcome. That, I believe, will become a differentiating element going forward.”

All of this requires more executive education and training, not just on specific cultures and languages, but increasingly to “help people become more conscious about their own cultural identities,” says Reiche. In research conducted with IESE colleague Yih-teen Lee et al., he suggested that cross-cultural training could include “modules that help people make sense of ‘who they are culturally,’ seeing alternative ways in which identity can be experienced, and understanding the impact of context and upbringing on their own identity development, so that individuals can develop and display desirable identity patterns in multicultural teams and in global work more broadly.”

Issues of identity have moved to the fore, something that the political scientist Francis Fukuyama discusses in his latest book Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment. “For the most part, 20th century politics was defined by economic issues. Politics today, however, is defined less by economic or ideological concerns than by questions of identity,” he writes in Foreign Affairs. “All over the world, political leaders have mobilized followers around the idea that their dignity has been affronted and must be restored. (This) resentment over indignities has become a powerful force… Identity politics is no longer a minor phenomenon… Instead, identity politics has become a master concept that explains much of what is going on in global affairs.”

Given these undercurrents, it’s paramount that executives are sensitized to the delicate dynamics inherent in multicultural teams and global work environments. Reiche stresses this point in Readings and Cases in International Human Resource Management: “One of the greatest problems is the lack of a global perspective on the part of a firm’s managerial cadre. As a member of one culture, the manager tends to see life from that perspective, to judge events from that perspective, and to make decisions based on that perspective. In an increasingly global business environment, such a perspective breeds failure.”

What’s needed are more leaders prepared to take a cooperative rather than me-first approach to help rebuild the foundations of society. In this effort, global businesses should take the lead. This is a point that Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum, made at Davos 2018. The world is experiencing a social crisis “every bit as threatening to the health of our future as the financial crisis was a decade ago,” he stated. “If the system is broken and the social contract is failing, business leaders around the world must play a leading role in repairing them.”

Schwab issued this rallying cry: “Over the past decade, the concerted international effort to deliver quantitative easing to our economies has been successful in rescuing us from the worst excesses (of the global financial crisis). This time, to create a shared future in a fractured world, we must focus on the qualitative impact of our decisions. What we truly and urgently need is a new social contract that provides real ‘qualitative easing’ for all those who have been left behind. We have it in our power to address the perils of a fractured world, but we will succeed only if we join our forces and work together – as joint stakeholders in our global society.”

Where will you be in five years?

PepsiCo’s Laxman Narasimhan says the answer to this question greatly depends on the people you bring with you, paying attention to these five keys:

Unrelenting curiosity Not just being curious enough to detect patterns across countries, but unrelenting in going beneath the surface to find the deeper reality.

Communication Particularly the way the new generation of workers express themselves, including nonverbal forms.

Humility Knowing which of the 10 plates you’re spinning to let drop, and when inaction is, in fact, action.

Resilience Recognizing “the beauty of strength” that comes from leading in turbulent environments.

Balance Not just between work/life but increasingly between performance and purpose.

As Reiche has written in his blog on cross-cultural management and global leadership, the backlash we’re experiencing today is not so much a failure of globalization as a failure of leadership – of failing to bring people along with us as our businesses change and evolve with the times. Business leaders must do better.

It seems obvious that closing borders is not a realistic, long-term solution. Yet, while globalization cannot be rolled back, it’s just as obvious that it does need a course correction. “Hence, leaders need to work together to distribute the benefits of globalization more equally and deal more explicitly with the costs of globalization,” Reiche says. “It starts by regaining people’s trust, restoring a positive outlook and creating a future vision that includes everyone.”

Nitin Nohria: “The 21st century will be a multipolar century”

02Global uncertainty

Nitin Nohria is the Dean of Harvard Business School and the co-author or co-editor of 16 books, including the Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice, with Rakesh Khurana.

People have said that the 19th century was the European century, the 20th century was the American century and the 21st century will be the Asian century. Harvard Business School Dean Nitin Nohria doesn’t buy into that. He thinks the 21st century will be “a multipolar century.” Here he comments on globalization’s accomplishments and shortcomings, and calls upon business leaders to focus their energies on coming up with entrepreneurial solutions that offer hope and a future to those who feel left behind.

What do you mean by a “multipolar” world?

It is a world in which multiple economic powers will end up being simultaneously important. This is very different from a world in which the Western economies used to dominate.

How do we get ready for a world like that?

First and foremost, we all need to have intellectual humility. If we only focus on American or European management practices, we aren’t preparing ourselves for innovation that is coming from China, India, Brazil, Africa, and other parts of the world that are fast emerging on the global stage. We need to be much better at sensing and embracing innovation that can occur anywhere in this changing world.

The global economic crisis and the rise of technology and automation have opened up fault lines in the success story of globalization. Is erecting barriers to protect your own labor the answer to the problems of inequality we’re experiencing?

I don’t think that encouraging protectionism will help. The forces of technology and globalization are too strong and too beneficial to be disrupted in this manner. We need to remember the lessons from economic theory and economic history that trade barriers will only make things worse.

You can’t protect workers from global competition without making the nation as a whole worse off. If someone else is going to be more productive or cost competitive, there’s no reason for anyone to pay higher prices for products that are made (and can be bought) much more cheaply than if they were made locally. The real problem is that we haven’t seen sufficient productivity growth in the advanced economies. That is the issue we should be trying to address.

“The societal problems we’re facing today require creativity and imagination”

But if labor keeps getting a declining share of the total pie of economic opportunity, won’t we end up with a series of political concerns that will actually constrain the license that business needs to operate?

Many are beginning to ask this very important question. We can’t ignore those who at one point enjoyed growing prosperity but now feel they have stagnated and been left behind by globalization. Moreover, they now are facing a future with AI and machine learning that looks even worse. We have to find a way of presenting these individuals with a more hopeful picture.

We will have to ask, “Do we have a responsibility to provide a living wage for our employees?” Because in the absence of holding our feet to the fire and saying, “We’re going to provide a living wage,” it’s easier to say, “I’m just going to shift production offshore. I’m going to have a call center and do all my manufacturing outside of Europe or the United States.” We have to be more imaginative than that.

What do you mean by imaginative?

Think of Henry Ford. He created the assembly line at Ford Motor Company. He also raised the minimum wage of his company’s workers significantly. He did so voluntarily and then found a way to make sure that the wage increase was sustainable by matching it with growing productivity and the rising demand for cars.

That’s entrepreneurship. We tend to think of entrepreneurship as creating a new company, but entrepreneurship also is creating a new business model or a new management practice.

What might such an innovation look like today? I’m not sure, but we have to find a business model that allows us to increase productivity so that we can grow wages for labor in the advanced economies – particularly labor that has low and middle skills.

So, what is it we can do?

We need to start analyzing jobs not in terms of starting salaries but in terms of their advancement potential. Much of what we’re teaching today may get people placed in jobs but doesn’t allow them to make upward progress. We need to start creating jobs and helping people develop the relevant skills over time that provide greater prospects for upward mobility.

We also need to start asking how we can help people who feel stuck today feel more hopeful. We must help the people who feel left behind find a path toward a future in which they can see a rising tide for themselves.

“We must help the people who feel left behind find a path toward a future in which they can see a rising tide for themselves”

This is the dark side of the globalization story. Not everyone has perceived the benefits. Is this something that our political leaders understand?

No, I don’t think so, otherwise we wouldn’t have been surprised by recent election results in so many different countries. In all these countries, there is a significant group of people who feel that globalization made them worse off and less hopeful about their futures. Now that group has started to exercise its political voice – and not just in the United States. We’re seeing similar reactions with Brexit, in recent European elections, in Brazil, and even in some Asian countries.

It’s not enough to point to the aggregate benefits of globalization – to the hundreds of millions of people around the world whose standard of living has been raised in the last three decades. That means nothing to the individual who no longer has a job and has seen his or her once thriving community devastated. Now these individuals are exercising their political voice in every part of the world and we had better pay attention.

Do you see any signs of hope?

Yes, the most hopeful signs come from innovative leaders and their companies. For example, there’s a company called Southwire operating in one of the industrial towns in the heartland of the United States. It has actively partnered with a local community college to develop the skills of the local workforce – to make these individuals more employable in its own plants and in other companies. Southwire’s investment in reskilling the workforce in its local economy (rather than just moving to another location) has led to an economic revival that makes everyone in the region feel more hopeful. We have begun to study and write cases on many other such examples of local economic revitalization.

We’re trying to determine to what extent these case studies are generalizable. Are partnerships between community colleges and companies a way to regenerate middle skills, or is this a limited solution? How many other parts of the United States might this work in? What models might work in other countries?

We need to scan the world to see what experiments companies are running. I’m optimistic that the inherent creativity of business leaders – and the role of business schools in tapping into that creativity to study and spread it – can generate answers to many of today’s most pressing economic and political challenges.

What’s your recommendation for business leaders?

Business leaders need to recognize that they have a real stake in solving the thorniest social problems. They can no longer leave these problems to governments or civic organizations. Indeed, they must take the lead to actively partner with other institutions to help solve these social problems.

The societal problems we’re facing today require creativity and imagination; they’re neither unsolvable nor someone else’s responsibility. We must view them as part of our jobs and apply our utmost energies to overcoming them.

Competitiveness must be complemented by inclusion

03Global uncertainty

Jorge Domecq: 4 keys to improve Europe’s security and defense

04Global uncertainty

Jorge Domecq has been Chief Executive of the European Defense Agency since 2015. Previously, he served as Ambassador of Spain to the Philippines and as director of the Private Office of the NATO Secretary General, among other roles.

Cross-border terrorism and tensions in the East, not to mention the United States’ changing priorities and growing isolationism, have put regional defense issues higher on the European agenda. “Europe must assume greater responsibility for its own security and defense,” Jorge Domecq asserts.

Here are four action items to build a stronger European defense:

1. Integrate and collaborate

“The current fragmentation of the European defense industry and market is a big problem,” Domecq says. For example, while the U.S. military has just one type of frigate warship, one type of main battle tank and one type of armored vehicle, European armed forces use a large number of different frigates, tanks and armored vehicles.

“We (in Europe) spent a little more than a third of what the U.S. spent (in 2017), but, according to some estimates, on the ground, we’re only capable of deploying about 15 percent of what the U.S. can deploy,” Domecq explains. Which is why the issue of more cooperation in Europe “is an existential issue,” in Domecq’s view. “If Europe wants to be a global actor going forward, we have to have greater defense integration.”

Nevertheless, Domecq clarifies that he is totally against industrial consolidation in Europe by decree. “It will never work,” he says. Success happens “when member states come together, agree on capability priorities and military requirements, and then turn to the industry to develop them.”

For a positive example of this kind of collaboration, Domecq cites the Meteor missile. “At present, there is one European company involving six countries with missile defense technologies. That has ensured that Europe has a third of the global share of the business of building missiles. If they hadn’t cooperated, we’d be out of business.”

Now, as a further means to deepen defense cooperation, 25 EU member states have signed up to the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO). Only Denmark, Malta and the United Kingdom have decided to opt out. Launched in December 2017, PESCO is a key step forward because of the binding nature of the commitments made by the participating countries to align and synchronize defense plans and maximize the effectiveness of spending. Countries enter into PESCO projects and the attached commitments voluntarily but, “like in a marriage,” with an ambition to respect the commitments and make it a success.

“In defense, we spend too much on personnel and too little on innovation”

2. Keep pace with technology

“New emergent technologies will change how we organize defense and its industry,” says Domecq, citing these examples:

- Artificial intelligence will be incorporated into both military and commercial unmanned and autonomous systems, which could, in the future, make them capable of undertaking tasks and missions on their own.

- Big data can help with simulation designs and results.

- 3D printing will revolutionize the way we produce tools and parts as well as how we organize logistics by providing parts on site and on demand.

3. Invest more in innovation

“Research and technology (R&T) are key for any modern defense,” says Domecq, noting that this requires investment and prioritization. A surprising fact is that, while overall defense spending is increasing, total defense-related R&T expenditure fell by 22 percent from 2006 to 2016. (Meanwhile, total R&D spending is down 6.5 percent over the same time period.)

Looping back to his earlier point about collaboration, Domecq laments that “in 2015, not even 8 percent of Europe’s defense R&T was spent collaboratively. This is the lowest figure in a decade.” (On a positive note: in 2016, Spain spent almost a third of its defense R&T in collaborative projects.)

It wasn’t always this way. The decades from the 1960s to the 1990s saw various countries collaborating in many programs, including the Panavia Tornado and Eurofighter Typhoon combat aircraft as well as several successful helicopter and missile collaborations. By contrast, there have been “no new major collaborative defense programs in the last decade.”

The result is “lower investment levels and fewer collaborative projects.” Meanwhile, European armed forces spend almost 50 percent of their budgets on personnel. “In short, we spend too much on personnel and too little on innovation.”

4. Open up to non-traditional players

In many cases, SMEs and nontraditional defense companies “are the source of new innovative research and cutting-edge technologies.” This makes it “more urgent than ever to draw on and attract SMEs and nontraditional defense companies into the industrial base,” says Domecq.

However, there’s hard work ahead. For defense, Domecq explains, when you’re in a warfare environment, you can’t afford to have a faulty switch: “It has to work.” That can mean onerous trials and lead-times that go against the usual frenetic rhythm of startups. Moreover, will the same companies on the cutting edge today still be around to help with updates and support in 20 years’ time? Another issue is the global nature of today’s supply chains, where some links in the chain might not comply with all security requirements.

“Innovation can bring a lot, but there are many questions to be answered,” he says. What the European Defense Agency needs to do, in his view, is “engage with European industry, at all levels, to support innovation.”

At this crossroads, Domecq believes that “if we can make European cooperation the norm, based on agreed priorities, sufficient funding and innovative technologies, then there will be a real step-change toward a European defense union.”

Peace: good for business

05Global uncertainty

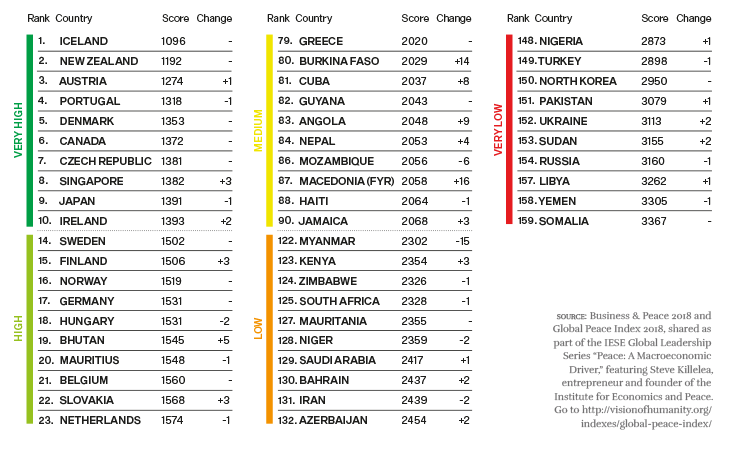

Economic performance and peace are mutually reinforcing: better economic performance assists in building peace, and vice versa.

The global state of peace

The 2018 Global Peace Index (GPI) shows the world is less peaceful today than at any time in the last decade. For a country to move up the ranking, there must have been improvements across a broad range of pillars, whereas a fall could be triggered by just a few factors, such as political unrest. Low peace countries are not necessarily places to avoid, provided they are making improvements on the pillars supporting peace. Of 163 countries ranked, we highlight 10 countries from each block, to give a snapshot of the global state of peace.

Peace by numbers

Improvements 71 countries were more peaceful in 2018 than in 2017

Deteriorations 92 countries were less peaceful in 2018 than in 2017

Overall average change GPI deteriorated 0.27%, the fourth successive year of deterioration

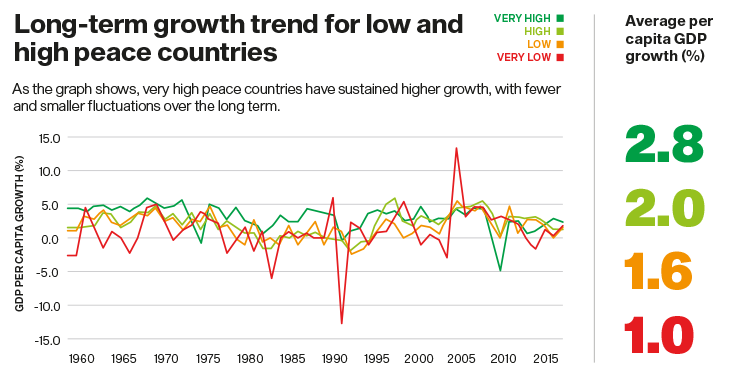

Effects of peace on business

More peace increases efficiency on both the supply and the demand sides. Increased trust in governance and third-party arbitration is one of the main effects on the supply side. That means greater participation of businesses and labor, and improved logistical efficiency due to reduced corruption. On the demand side, more peace translates into reduced frequency and impact of unexpected events, and greater incentive for investing and purchasing. That’s important because, looking back over the past 70 years, per capita GDP growth was around three times higher in highly peaceful countries versus those with very low levels of peace.

Pillars of peace

A robust business environment springs from a background set of eight interconnected conditions:

1. Well-functioning government

2. High levels of human capital

3. Equitable distribution of resources

4. Acceptance of the rights of others

5. Free flow of information

6. Low levels of corruption

7. Good relations with neighbors

8. Sound business environment

Download Peace: good for business

Are we perceiving more polarization than there actually is?

06Global uncertainty

When Donald J. Trump was elected president of the United States, many people fixated on what could have motivated voters to choose him. Was it the promise to build a border wall to keep Mexicans out? Mass deportations of undocumented migrant workers? A ban on Muslims entering the country? Voters must have been swayed by his extreme views on immigration, people speculated, and therefore all Trump supporters must be racist xenophobes, they surmised.

Is this generalized inference about Trump supporters accurate? Or, putting political leanings aside, might we be seeing a more basic cognitive heuristic at work?

This is essentially what prompted a study by Kate Barasz, working with Tami Kim and Ioannis Evangelidis, to test cognitive biases in both political and nonpolitical contexts.

In psychology, heuristics are those simple, efficient rules we tend to lean on in order to help us form judgments and make decisions regarding complex matters. Research has found that these sorts of mental crutches can produce erroneous inferences and influence broader beliefs, which makes understanding them important.

For their paper, Barasz et al. designed seven studies to learn more about what they call the “value-weight heuristic” – that is, a tendency to overweight more extreme positions to arrive at quick judgments.

In their first study, they looked at the assumptions that supporters of Hillary Clinton made about Trump voters, and vice versa, and considered their accuracy, just five days after the presidential election. Using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk crowdsourcing site to screen participants, 300 Clinton and Trump voters were asked about their reasons for voting and their assumptions about why others voted the way they did.

The results offered initial evidence of a value-weight heuristic and its possible consequences. So, Clinton voters tended to believe that Trump’s extreme immigration policy was important in his supporters’ decision to cast their votes, yet Trump voters themselves put more weight on his economic policies, a less extreme issue. What’s more, Clinton voters who surmised that Trump voters put more weight on immigration viewed Trump voters less favorably overall.

If people infer an entire group is singularly motivated by an especially extreme or divisive policy issue, perceptions of political polarization are only likely to grow

Consider: if someone believes in the border wall and a Muslim ban, they may well have voted for Trump. But it’s weaker, logically speaking, to assume that if they voted for Trump, they must support his extreme views on immigration. This is essentially turning the tables on cause and effect. Trump voters may, in fact, care more about his infrastructure spending promises. Yet, when extreme views are in the mix, here the co-authors find evidence that people have inferential blind spots.

From political climate to actual climate

To remove politics from the equation, Barasz et al. turned to a more neutral topic: the weather. Their second study asked more than 200 participants about the climate in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and Fort Worth, Texas, and how important that weather was to a hypothetical person’s decision to move there.

As expected, participants who considered the weather more extreme in either location were also likely to give it more weight in someone’s decision to move there. Does that mean the availability of jobs, family ties or other factors are less important in Florida moves? They find, once again, a tendency to conflate value and weight, supporting their main finding that a value-weight heuristic is at play.

Five other studies, involving more than 2,000 participants, corroborated the main finding that, whether it’s a political stance or the weather, the more extreme the feature, the easier it is – and the more confident and likely we, as human beings, are – to assume we know what motivated that choice.

Why is this important? For one thing, political polarization seems to be growing, not just in the United States but all around the world. How we come to perceive others’ attitudes – and what we believe they prioritize – may contribute to our observations of further polarization.

This research suggests that the value-weight heuristic may be especially relevant and consequential where extremity, such as intense policy stances and conspicuous platform issues, can distort observers’ perceptions, regardless of party affiliation. That can render observers insensitive to other factors that could have motivated their choices.

In sum, if people infer an entire group is singularly motivated by an especially extreme or divisive policy issue, perceptions of political polarization are only likely to grow. And the more that happens, the less likely it becomes to really understand where the other side is coming from.

Making people aware of their inference blind spots or over-inference tendencies could actually help reduce political polarization. Now wouldn’t that be nice?

Ask yourself…

- What business positions or people have I dismissed for their apparent “extremity”?

- Might I have made erroneous inferences about them?

- What additional research could I do to gain a deeper understanding?