SustainAbilities

01SustainAbilities

The post-pandemic era demands a new type of leader, capable of understanding, aligning, innovating and committing to build a more sustainable world.

At the end of the U.N. climate summit in Glasgow on Nov. 12, 2021, activist Greta Thunberg famously tweeted: “The #COP26 is over. Here’s a brief summary: Blah, blah, blah. But the real work continues outside these halls. And we will never give up, ever.” Talk is cheap, admitted Xavier Vives, professor of Economics and Finance at IESE, writing for Project Syndicate. But sometimes “cheap talk is the first step toward agreeing on a common course of action.” And international gatherings that at least “raise awareness about the problem and potential solutions (are) better than the denialism of past years.”

Hot on the heels of COP26 was IESE’s Global Alumni Reunion (GAR), held Nov. 11-13 on IESE’s new Madrid campus, featuring a hybrid format that enabled thousands to connect and follow the event online, as 35 policymakers and business leaders stressed the need to put stated sustainability goals into practice. The overarching message was clear: The time for talk has ended and the time for urgent action is now. And business must take the lead, first by understanding the scale and scope of the challenges ahead; then aligning operations and stakeholders accordingly; innovating bold and ambitious solutions; and making clear, measurable commitments toward a more sustainable world.

Understand

The climate emergency requires a fundamental shift in mindset. Sustainability has moved far beyond a narrow definition of minimizing damage to the environment; instead, it’s about maximizing long-lasting positive impact on people and the planet, and rejecting short-term gains that disregard the health and lives of people and the world today and tomorrow. It’s about pursuing the common good, fighting inequality and seeking justice, not to mention planetary repair – in short, “the very things that we consider to be at the heart of good management,” says IESE Dean Franz Heukamp.

“Sustainable leadership requires every leader to think about his or her role, not only as a leader in a defined space, but also as a worldwide citizen with a longer-term impact on society and the planet,” says IESE professor Yih-Teen Lee. This echoes a point made by Inger Ashing, CEO of Save the Children International, who urges business leaders and the private sector to think about the implications of their actions on current and future generations of children, who will be affected first and worst by the climate crisis (see below).

Inger Ashing

CEO, Save the Children International

We must do better

In Save the Children’s recent report, “Born into the climate crisis,” research led by the Vrije Universiteit Brussel set out the devastating impact of the climate crisis on children.

Using the original Paris Agreement emission reduction pledges, the data show that a child born in 2020 will experience, on average, twice as many wildfires, 2.8 times the exposure to crop failures, 2.6 times as many drought events, 2.8 times as many river floods and 6.8 times more heatwaves across their lifetimes compared with a person born in 1960. Extreme weather events are affecting children first and worst, with grave implications for the rights of current and future generations.

We know that children living in low- and middle-income countries who have done the least to contribute to climate change will bear the brunt of its impacts. For the most vulnerable – including those living through conflict, those impacted by COVID-19 and those experiencing inequality and discrimination – the reality will be even worse.

These harsh realities should serve to focus business minds on reducing emissions. Using the same modeling as before, if global warming were limited to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, the risk of additional exposure for children born in 2020 would significantly decrease – by 45% for heatwaves, 39% for droughts, 38% for river floods, 28% for crop failures and 10% for wildfires. Lowering the risk of exposure to extreme weather events means more children would remain in school, malnutrition would be avoided and, ultimately, the lives and futures of many of the world’s most vulnerable children would be saved.

Private sector actors have key roles to play in leading the transition to sustainable, carbon-neutral economies, such as by divesting from fossil fuels and creating greener jobs. Businesses should examine the environmental impacts of their products, actions and business relationships, particularly focusing on the effects on children. This should be done in accordance with the U.N.’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the Children’s Rights and Business Principles.

Around the world, children are standing up for their rights and for the climate, sharing their firsthand experiences, bold ideas and innovative solutions. Despite this and despite the direct and disproportionate threat they face, children are routinely excluded and overlooked in climate discussions, policies and summits. As children exercise their rights to campaign and influence change, they deserve to be included, with the respect and support of adults, in climate decision-making processes.

We invite business leaders to examine their own practices, to listen to children’s views and recommendations, and to use their positions to close the climate financing gap, raise greater awareness of the climate crisis and influence others to act. Despite the overwhelming scientific, economic and moral cases, so far we are failing to do enough. Children around the world will pay the price of inaction with their lives. We must do better.

MORE INFO: “Born into the climate crisis: Why we must act now to secure children’s rights” by Save the Children International (2021).

To help leaders rethink their wider roles and responsibilities, IESE has launched the Sustainable Leadership Initiative, led by IESE professor Fabrizio Ferraro. The goal is to advance interdisciplinary research on corporate strategies, business models, investment practices, accounting rules, public policies and consumer behavior. It’s vital to see the big picture and understand the links between climate change, the pandemic, inequality, societal wellbeing and business success.

It’s vital to see the links between climate change and business success

Recognizing that how executives and future leaders think about these issues is often shaped by what they learn in business school, IESE is taking its role as an educator seriously and making sustainability an integral part of the core curriculum across MBA and executive education programs. Also in 2021, IESE joined forces with seven other leading European business schools – Cambridge Judge, HEC Paris, Spain’s IE, Switzerland’s IMD, France’s INSEAD, London Business School and Oxford Saïd – to form a new coalition called Business Schools for Climate Leadership (BS4CL). These B-schools together train more than 55,000 students and executives per year and boast over 400,000 alumni in key sectors around the world. These faculties will use their collective knowledge and research insights to accelerate the business response to the climate crisis. Their first release was a climate leadership toolkit, timed to coincide with COP26, which is freely available at BS4CL.org. In it, IESE’s Mike Rosenberg considers the impact of climate-driven geopolitical dynamics on business strategy.

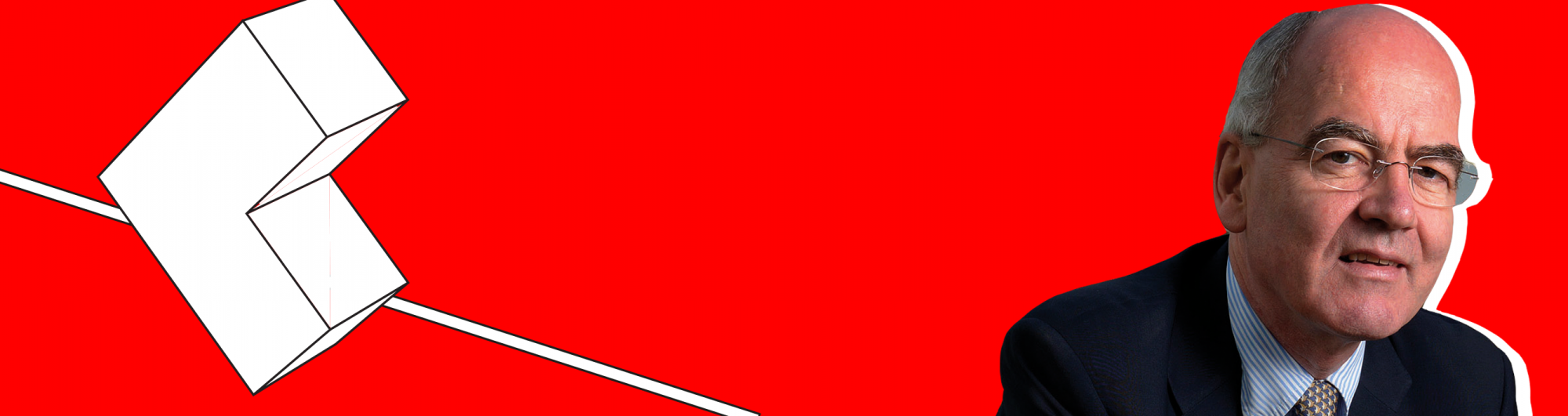

Mike Rosenberg

Professor of the Practice of Management,

IESE Strategic Management Department

Glasgow half full

In November 2021, world leaders, CEOs and thousands of other delegates converged on Glasgow for the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. These meetings have been going on ever since the convention was first adopted at the Earth Summit in Rio in 1992, reaching a high point at COP21 in Paris in 2015 when 195 nations agreed to reduce their carbon emissions in order to keep the average increase in global temperatures below 2°C, preferably to 1.5°C.

One problem with that agreement was that it relied on each country setting its own targets, called nationally determined contributions (NDCs), which countries revise every five years and then can adjust their commitments as necessary to achieve a global reduction in emissions over time. Taking stock after the first five-year round, we see that the sum total of the NDCs is still far from where it needs to be to avoid the worst-case scenarios of climate change. Looking at that, one could conclude that, after almost 30 years, the governments of the world have still not figured this out. Alternatively, one could say that we are getting there, slowly.

For me, the good news is that the Glasgow conference did make some progress on commitments to phase out (or phase down) coal, halt deforestation and put limits on methane, among a number of other measures. There was even some progress on the need for wealthier nations to finance the energy transition in developing countries, although we are still short of the $100 billion annual investments called for at COP21 in Paris. Also important was a joint declaration by China and the United States to work together to enhance climate action.

We also saw more and more companies, cities and regional governments making their own commitments to reaching net zero by 2030 or 2035. The reason I prefer to see COP26 in Glasgow as half full, rather than half empty, is mainly because of that. As Schneider Electric’s Vincent Petit writes in his book The age of fire is over, the transition will happen because the market will demand it. And with key technologies providing unanticipated services at lower costs, we are seeing not only the market demanding it, but companies committing themselves to leading the transition to a low-carbon economy. The transition has begun, and with it, quite possibly the largest business opportunity in history.

READ Mike Rosenberg’s blog Doing Business on the Earth.

As well as broadening and deepening executives’ understanding, BS4CL illustrates another key factor for progress on sustainability: the importance of working together, even with your competitors, to advance common goals. As business leader Paul Polman noted at the launch: “Siloed thinking and institutional rivalry are our enemies in these urgent times. New partnerships are essential for bringing speed and scale to our response to the climate crisis.”

Align

The need to work in partnership with multiple stakeholders and align competing interests is paramount. “As we have seen with the pandemic, when we all come together, between the public and private sector, great things can happen and at speed,” Citi CEO Jane Fraser told IESE alumni.

Collective action will be even more effective if individual companies and certain key industries each play their part. Financial institutions, for example, can serve as catalysts for transitioning businesses to cleaner technologies by financing green projects, said Fraser. >>

Vivian Hunt DBE

Senior Partner, McKinsey & Company

Businesses should serve all stakeholders

COP26 saw leaders and companies pledging to commit to net zero. Are their pledges sincere? We should take them at their word. Of course, the delivery won’t be easy, but aspiration in itself is a good thing. As the 19th-century English poet Robert Browning wrote, “A man’s reach should exceed his grasp.” Or, I would add, a woman’s reach.

Stakeholder capitalism puts forward that we, as business leaders, should seek to serve not just shareholders but also employees, suppliers, communities and the planet itself. How do we go about that? Truly embracing it – and by that, I mean embedding it as a core component within your business strategy – is not always easy, but the long-term benefits far outweigh the short-term costs. To execute stakeholder capitalism, companies are increasingly putting ESG concerns at the heart of their business strategies.

It is important to be rigorous in identifying actions that will continually move the needle. Look closely at each element for strategic opportunities, expanding on what you already do well. For example, in G (governance), differentiators might include better data privacy, enhanced cybersecurity protection or more board diversity. To this last point, board diversity should go beyond gender and ethnic diversity to include different skillsets and lived experiences. That way, they will represent a broader set of stakeholders, including nonprofits, activists, community members and young people. A more diverse board will ask different – and often tougher – questions about resources, supply chains, social issues and so on. But that’s good and can lead to a financially healthier and more resilient company in the future.

Those who resist the direction of change will likely find themselves on the wrong side of history and at a competitive disadvantage. Why? Because stakeholder capitalism is intrinsically a long-term play, and a long-term perspective is good for the best companies. Really, stakeholder capitalism is the process and inclusive growth is the result.

Ana Claver

Managing Director of Iberia, U.S. Offshore and Latin America, Robeco

President, Sustainability Committee, CFA Society Spain

Work together for big impact

We’re at a pivotal point in history and there’s really no choice: If we want to have a sustainable recovery, we need to have a sustainable economy, and for that there are three conditions that need to be met.

First, we need a healthy planet. Second, wealth and wellbeing need to be fairly shared. The protests we’re seeing all over the world are ultimately about inequality, poverty and not having equal access to healthcare and a good education. Those issues need to be addressed. Third, we need to have proper governance, both at the corporate and government levels.

As an asset manager, we align our activities on these points. We started adopting sustainability in the mid- ’90s and it has been at the core of our business since the mid-2000s. Sustainability is treated like any other value driver, and ESG criteria are fully integrated in our investment processes for all our asset classes.

Given the immediate health crisis, it’s normal that leaders are focusing on that right now. But we can’t just think short-term. Amid so much volatility, it’s all the more important to maintain multiple contacts with clients, explaining what’s going on and assuring them that you’re working on their behalf, always focusing on sustainability and the long term.

It’s not something that any single organization can do by itself. It requires concerted effort from investors, asset managers, governments and other stakeholders to make this happen. For example, as part of the Climate Action 100+ group, we engage with the largest greenhouse gas emitters and urge them to take necessary action on climate change, such as getting them to put climate specialists on their board and change their direction.

As one actor, you can make some difference, but it’s more important to realize that if you align yourself with others, all working together toward getting wealth and wellbeing equally distributed, then you can make an even bigger difference.

Sustainability is an active decision: You have to make a choice to invest in companies that create value for all stakeholders, not only shareholders. At Robeco, we believe that all the stars are aligned for sustainable investment, and we’re more committed than ever to contribute to that shift.

>> Consider the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), a collection of 450 banks, insurers and investors led by U.N. climate envoy Mark Carney. With a combined $130 trillion of private capital committed, this group has promised to put combating climate change at the center of its work. A GFANZ member herself, Fraser noted that her organization, Citi, has pledged $1 trillion to sustainable finance by 2030.

“The money is here,” Carney told COP26, “but that money needs net zero-aligned projects and (then) there is a way to turn this into a very, very powerful virtuous circle.”

“The financial sector’s role in transferring resources from brown to green technologies will be crucial,” agreed Vives. And while the reason for divesting from dirty assets may be a self-interested one to lower risk rather than any moral motive, that self-interest is increasingly aligning with broader societal interests, which are progressively more attuned to the systemic risks posed by climate change.

Even in alignment, the best course of action is hardly ever going to be linear

Even in alignment, don’t expect progress to be linear. “The best course of action on climate change – whether at the government, investor or corporate level – is hardly ever going to be linear, clear and publicly lauded,” says IESE’s Ferraro. In his research with Dror Etzion (McGill University) and Joel Gehman (George Washington University), Ferraro calls for “robust action” that keeps all actors in the game, even when their diverging interests threaten to complicate the rules. In a study of chess players, it was observed that the best players were able to pursue a strategy while being flexible enough to adapt in the face of their opponents’ moves. Likewise, Ferraro advocates for approaching grand challenges by keeping options open, even when some participants seem to be trying to block them.

Working across sectors and countries, keeping everyone engaged is key. Following COP26, Ferraro wrote: “This is a marathon, not a sprint, and we will need many more COPs to make meaningful progress, but what matters is that we keep acting, together.”

In terms of international alignment, the gap between the developed and the developing world is particularly difficult to bridge. As Fraser noted, financing should be directed to those who can’t afford the upfront costs and investments to get off the fossil fuels that are cheaper right now. We in the developed world benefit from lower costs in developing countries, making us part of the problem. This puts greater responsibility on multinationals to help finance the transition to more sustainable practices.

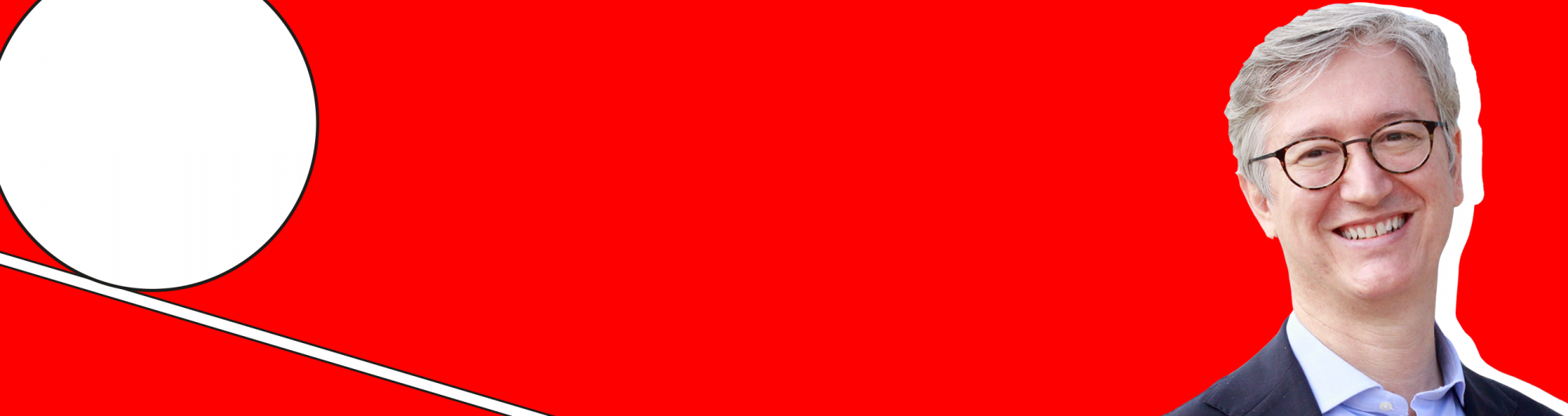

Govert Vroom

IESE Professor of Strategic Management

The case for collaboration

An IESE case study on WWF and Greenpeace – recently highlighted by the Financial Times Responsible Business Education Awards – explores to what degree organizations with similar environmental goals can collaborate while maintaining their distinctiveness.

Collaborating with competitors and aligning stakeholders for greater impact in areas of shared concern would seem to make sense when it comes to tackling planetary-level problems that no single actor can solve alone. That was the thinking of the two largest environmental NGOs in the world – the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Greenpeace – which viewed the worsening situation in the Arctic with growing alarm. Both organizations were already present in global and local forums to establish common environmental goals and agendas, but as one remarked, “We agree on the objectives but then pursue them separately.”

Although organizations may agree on the problem, sometimes their strategies could not be more different. In 2017, a major international treaty was signed to protect the Arctic. But as frequently happens, individual government priorities subsequently shifted, putting at risk hard-won agreements. Bans on Arctic oil drilling were reversed, and some saw record-high sea temperatures as an opportunity for shorter sea-shipping routes through the Arctic. “It feels like we keep winning battles but losing the war,” despaired one activist.

Given the feeling of the clock winding down on the Arctic, both WWF and Greenpeace, in common with a growing number of other organizations, are convinced that they will need to pool resources and capabilities to effect lasting change. But how?

Before collaborating with others, it’s vital that you understand your own unique market strategy, operational methods and organizational culture. You need to have your own purpose and values clear to ensure that whatever you decide to do collaboratively will be consistent with your core; in other words, your alignment with others must be in alignment with yourself. Being clear about that will help draw out areas of complementarity and synergy, while maintaining your integrity.

When allying with competitors, you must also be clear about your own sources of competitive advantage. This will help you advance common agendas without compromising your own competitiveness.

In the end, it’s about setting the terms of the collaboration in ways that boost the common good, without degrading any of the participant parts in the process. This is how the whole can become greater than the sum of its parts.

MORE INFO: “WWF and Greenpeace: Two Strategies to Save the Arctic Ocean” (SM-1677-E) and the associated teaching note (SMT-124-E), by IESE professor Govert Vroom, Ramon Casadesus-Masanell, Isaac Sastre Boquet and Jordan Mitchell, are available from IESE Publishing, which this year celebrates its 20th anniversary. Another case by Govert Vroom, on the music streaming giant Spotify, is currently IESE Publishing’s best-selling case.

Innovate

Achieving sustainability in the coming decades will hinge on innovation. Companies must look for new business models, new ideas, new processes and new raw materials if they are to truly change their way of doing business. This shift is the difference between optimizing energy usage and discovering entirely new energy sources. Optimization is important but has proven to be insufficient to the task of stopping planetary degradation. Innovation may be the difference between 1.5°C and 2.5°C.

“The changes that we will need to undertake to transform our economy toward more green, sustainable development are massive – much more than what we’ve been doing up to now,” says IESE professor Nuria Mas. So massive, in fact, that Mas is preparing for the possibility of what’s known as a commodities supercycle – outsized demand for certain materials – on a par with the industrialization of the U.S. in the early 20th century and the reconstruction of Europe after World War II.

Large companies, with their resources and clout, have a particular obligation to lead innovation.

Achieving sustainability in the coming decades will hinge on innovation

In addition to investing in R&D, that means working with universities and research institutes, as well as cutting-edge startups. “Relevant companies such as ours need to move the whole sector in the direction of sustainability,” said Pablo Isla, who at the time of the GAR was the Executive Chairman of the Spanish fashion giant Inditex, which counts Zara among its stable of well-known brands.

Sustainability is prompting a radical overhaul of the fashion business, as global brands work to find new approaches to how clothing is designed, made and used. For its part, Inditex has implemented projects to reduce emissions, source new fabrics, train their teams and search for new ways of recycling on their way to circularity. Since launching its first multi-year sustainability plan in 2002, Inditex has committed to making 100% of the cotton, linen and polyester used by its brands organic, sustainable or recycled. In its stores, it uses recyclable packaging and monitors energy use. It also works with NGOs on a global take-back program to distribute used clothing to people in need. Its Join Life labeling identifies which garments are more sustainable, thereby allowing consumers to choose sustainability.

But the key to continuing to deepen its sustainability efforts is innovation in areas such as new textile recycling techniques, in the creation of new fibers with sustainable technologies, in new methodologies to improve maintenance and extend the life of garments, and in garment biodegradability.

Javier Goyeneche

Founder, Ecoalf

Because there is no Planet B®

The fashion industry is one of the most polluting, based on an unsustainable business model of “buying-throwing.” But we have an opportunity to redefine the business model into a circular model through recycling and upcycling. Ecoalf was born in 2009. Both the brand name and concept came after the birth of my two sons: Alfredo and Alvaro. I wanted to create a truly sustainable fashion brand, and I believed the most sustainable thing to do was to stop using natural resources in a careless way to ensure those of the next generation. Recycling could be a solution if we were able to make a new generation of recycled products with the same quality and design as the best non-recycled ones.

We’ve developed over 450 recycled fabrics from different types of waste. For example:

- For our 2021-22 fall-winter collection, we recycled more than 4.5 million plastic bottles. A single-use plastic water bottle might have had less than a 30-minute life span; we recycle it and give life to a coat that can last for 30 years.

- Coffee has a lot of natural properties that are beneficial in clothing: fast drying, odor control, UV protection. We blend post-consumed coffee grains with recycled nylon or polyester to infuse our jackets with these natural properties; otherwise, you need to add chemicals to achieve the same effects.

- Fishing nets are made of the best nylon. An old fishing net can be recycled into a jacket in seven chemical steps instead of 17 steps if we had started with virgin nylon (from petrol). This process uses less water and energy, generating fewer emissions.

One of our most ambitious projects was born when Spanish fishermen invited me to go out fishing with them on their boat so I could witness this for myself: Every time they pulled up their nets, there was waste that got tossed back into the ocean, only to be picked up again the next day. So, I started the Ecoalf Foundation and created the project Upcycling the Oceans, whereby we give fishermen waste containers, so instead of throwing it back, they bring it to port, where they drop it into bigger containers. Each week, we collect this waste, and separate and classify it. We recycle around 68% of what we collect, around 10% of which is PET that we keep to make our ocean yarn for Ecoalf coats and sneakers. We’ve expanded this project to Thailand, Italy and Greece. For 2025, our goal is to have 10,000 fishermen doing this across the Mediterranean, effectively cleaning the bottom of the ocean where 75% of marine waste resides.

You may have heard the phrase “Because there is no Planet B” but not known that it’s our registered trademark and it is bringing together millions around the world to be part of the change with our Ecoalf Movement. In 2018, we were the first Spanish fashion brand to become a certified B Corp.

Although we aspire to 100% circularity, we’re not there yet. We need to make sure all our products are apt for future circularity – not just downcycling (to a lesser product) but true recycling or upcycling. There are tradeoffs. Sometimes we must choose between durability and circularity. Now we think circularity is more important, but since the technology is still not there in terms of chemically recycling, we also advocate for durability. And we hope consumers change their habits to consume less.

All this requires a lot of investment. While we don’t put 35% of sales back into R&D like we used to do, continuing to invest in R&D remains crucial.

“There’s a huge challenge in R&D and innovation to get us closer to zero carbon emissions,” says IESE’s Rosenberg, citing the needs of heavily polluting industries such as cement, steel and glass. “In some industries, brand-new technology that has never existed before is needed.”

At Inditex, the demand for planet-friendly products comes from every level. “This is not something that we just decide at the top levels of the company,” said Isla. “It’s something that is coming from our people. Several years ago, we could say it was mainly younger people, but now sustainability is absolutely intergenerational.”

Francisco Reynes

Chairman and CEO, Naturgy

Innovation for 360º sustainability

The dizzying pace at which 21st century society evolves means that we run the risk of distorting the concept of sustainability, which at root is about pacing ourselves for the long term. As such, we need to lay durable foundations so that the decisions we make today are solid and lasting. This involves considering not only environmental but also social and economic aspects of each decision. A focus on these three areas will ensure and even improve the wellbeing of the world’s population.

To face the transformation ahead and to help combat climate change, one of the main levers at our disposal is innovation, especially technological innovation – from renewable generation and renewable gases to energy storage and sustainable mobility. The Next Generation EU public funds should help in this effort, although it is also essential for the private sector to commit to and execute such projects.

As vital as technological innovation is for the energy transition, we must not neglect people in the process. To ensure a fair and just transition, we must guarantee that energy is available to all and that the new employment opportunities created over the coming years will serve as a wider source of wealth generation and social development.

Another necessary condition for achieving sustainability is the transformation of companies. Whether responding to transversal digitalization or to society’s new demands, businesses must adapt their organizational cultures to allow for greater flexibility and diversity in teams.

For all these reasons, we, at Naturgy, began a profound transformation a few years ago. To promote the energy transition, we put our stakeholders at the center of all decision-making, maintaining an explicit and courageous commitment to environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles and criteria.

As the adage goes, if you want different results, don’t keep doing the same things over and over again. To remain competitive, it’s time to try new things.

READ MORE: “Standards and transparency are essential to a sound energy transition,” from IESE’s 8th Energy Prospectives meeting, one of a series held in collaboration with the Naturgy Foundation.

Commit

The final important step is to make commitments that are public and that have clear targets. Pledges to achieve net zero mean that what you do today really matters. It starts now.

In his book, Falling in love with the future, IESE’s Miquel Llado draws on the theory of 1,000 days (devised by his late colleague Paddy Miller) which observes that managers only stay in each of their positions an average of three years before moving on. This time constraint implies that you should use your time judiciously and be very focused to achieve your objectives within that timeframe. As seen in the half-lives of radioactive isotopes, time can deteriorate the power to enact meaningful change. This underscores the importance of taking urgent action now to accelerate progress toward the ambitious U.N. Sustainable Development Goals that the business world pledged to achieve by 2030. With only nine years left, corporate leaders should not be resting on their laurels but can and should be doing more, says Ferraro.

Stephen Cohen

Head of EMEA, BlackRock

Committed to change

Each year, BlackRock’s CEO, Larry Fink, writes a letter to the CEOs of the public companies that BlackRock is invested in on behalf of our clients. The 2020 and 2021 letters focused on how climate risk is investment risk and a historic investment opportunity. We see climate risk as different from other financial challenges in that it’s not a short-term blip but a much more structural, long-term transition for which investors must be prepared for a significant reallocation of capital.

BlackRock’s work on sustainability is rooted in our fiduciary duty to help clients understand, navigate and drive the successful management of sustainability risk in their own portfolios. In 2021, we incorporated the impacts of climate change into our Capital Market Assumptions (CMAs), which are a key building block of how we design and implement portfolios, to help clients account for the investment risks and opportunities from the energy transition to net zero. Our CMAs assume a successful transition to net zero and currently estimate a 25% cumulative gain in GDP by 2040, compared with business-as-usual.

To that end, we have built an extensive sustainable investing platform encompassing index and active funds across all asset classes, designed to help clients meet their sustainability and financial objectives.

Just as investors have embraced index investing in traditional portfolios, we are providing Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) equivalents to our flagship products and launching innovative thematic products to further steepen the adoption of Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs). Globally we now have more than 250 sustainable mutual fund and ETF offerings.

Our broad spectrum of sustainable strategies supports our clients in achieving their investing goals, from reducing exposure to fossil fuels or minimizing carbon emissions to alignment with climate goals.

It’s time to leave the term “passive investor” behind. Today’s climate-concerned investors want products that actively reflect their sustainable investing goals.

READ MORE about BlackRock’s commitment to sustainable investment.

“I’ve never seen such a consensus that we have to start acting now,” adds Rosenberg. Why? “One reason, which is very clear, is that the younger generation have said, ‘It’s not fair for us that this is happening.’ And they have really changed the conversation, not only at the U.N. but in people’s dining rooms. Another part of the story is that Mother Nature is telling us that now is the time to act.”

While now is the time to act, acting in concert on a global level is patently difficult, as evidenced by some of the watered-down commitments coming out of COP26. Still, there is progress. A promising example: the commitment by over 100 nations to cut 30% of their methane emissions. EU Commission chief Ursula von der Leyen said cutting methane was not only effective in the short term, but also “the lowest hanging fruit,” meaning it is relatively easy to accomplish by fixing leaks from natural gas lines and oil wells as well as taking other measures that are already possible with existing technology.

The low-hanging fruit is ripe for picking in so many areas that matter

The low-hanging fruit is ripe for picking in so many areas that matter. Notably, there has been talk about mandatory sustainability reporting. This is a crucial step in the move from shareholder to stakeholder capitalism. To move forward efficiently, IESE’s Gaizka Ormazabal is among those urging that we start with carbon reporting, leaving the S and G of ESG standards for later.

Carbon disclosures should be mandatory for all companies. International standards are in place, thanks to the International Greenhouse Gas Protocol, and they are not too onerous, even for smaller companies. This is the recommendation of Ormazabal and five coauthors in their well-argued brief, forthcoming in the Management and Business Review. The proposal sounds simple, which is exactly the point. The sooner they start reporting, the sooner companies can then start making direct, cross-industry, yearly comparisons, allowing them to make more rigorous predictions, and allowing investors and other stakeholders to chart progress – or lack thereof.

Although carbon disclosures are not yet mandatory in most countries, that is no excuse to avoid making such disclosures anyway. A new paper by Patrick Bolton and Marcin T. Kacperczyk finds that voluntary carbon disclosures can lower the cost of capital for companies and increase the accuracy of estimated emissions for non-disclosing firms, with positive spillover effects for society.

Jose Maria Alvarez-Pallete

Chairman and CEO, Telefónica

Put your money where your mouth is

With around half the Sustainable Development Goals requiring some sort of digital solution, a global telecom like ours has a key role to play. We believe it is our duty to take advantage of the capabilities of connectivity and digitalization, not only to bring value to our customers, but also to help tackle major challenges such as climate change, inequality, employability and misinformation.

To this end, we established a corporate Responsible Business Plan, which specifies the products and services we will pursue for sustainability, privacy and security, ethics, human capital, governance, suppliers, the environment and climate change. This plan is monitored at the highest level, by the Sustainability and Quality Committee of our Board of Directors. In fact, Telefónica was the first Ibex 35 listed company to have such a board committee (since 2002). This committee oversees month-by-month implementation of the Responsible Business Plan, ensuring its reporting and compliance.

We detail our progress in an annual Integrated Management Report, prepared in accordance with the main international reporting standards: the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). In addition, we measure and report our impact in relation to fiscal transparency, the Sustainable Development Goals, and transparency in communications. And our efforts are recognized by prestigious indices such as the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, the Carbon Disclosure Project and Sustainalytics.

Putting our money where our mouth is, we make customer satisfaction, gender equality, social trust and CO2 reduction part of our employees’ variable remuneration. We have committed to decoupling business growth from greenhouse gas emissions and we are working to decarbonize our operations so that we can reduce our emissions by 70% by 2025 and by 90% in the four main markets of Spain, Brazil, Germany and the U.K., as well as achieve net-zero emissions by 2040 at the latest, including in our value chain. In 2021, we decided to issue green, social and/or sustainable bonds. By linking financing to projects and the sustainability targets/KPIs by which they are evaluated, we are further integrating sustainability in all business strategies and company practices.

We do all this based on the conviction that only companies that take responsibility for their actions with society and the planet will be relevant in the future.

While there are lots of things that companies can do voluntarily to understand, align, innovate and commit to change, there’s no doubt that governments also have an important role to play. “Governments need to put regulations and incentives into place to make this transformation happen, while also helping to reduce the cost of the transition as much as possible,” says IESE’s Nuria Mas.

“The key thing about growth, sustainability and inclusivity is that they are extremely interconnected. In the past, this has led to a negative spiral and to the situation that we find ourselves in today. But this interconnectivity also means the converse is true: If we can succeed in making growth compatible with inclusive and sustainable development, then we can enter into a positive spiral.”

“All of us will have to step up our investments and commitment,” Mas adds. “But the upside of implicating so many different individual actors is that everybody is included, and the global benefit will be felt by all.”

MORE INFO: Missed the Global Alumni Reunion or couldn’t catch all the sessions? You can access the sessions on the event’s official website. Note that e-conferences are exclusive to Members of the Alumni Association. If you aren’t yet a Member, consider activating your membership today and take advantage of the many resources made possible through membership.

WATCH: “Business trends 2022: Putting sustainability into action – now”

John Elkington: “We need to go faster”

02SustainAbilities

John Elkington is the founder and Chief Pollinator at Volans. A pioneer and world authority on sustainable development, he is the author of 20 books, including Green Swans: The Coming Boom in Regenerative Capitalism, earning him the moniker “the Godfather of Sustainability.”

John Elkington is known for coining simple yet powerful memes – including “the triple bottom line” – which cut through the noise and become buzzwords that stick. His current job title – Chief Pollinator at Volans, a thinktank and advisory firm to drive system change – is another such example. “It made sense to me,” he explains, “because one of the signs of the accelerating collapse of natural systems around the world is the disappearance of pollinators. It reflects what I do: learning from people and spreading their lessons to others through speaking, writing and consulting.”

Here, he discusses what is meant by Green Swans and why, despite foot-dragging by businesses, he remains ever hopeful.

We know about Black Swan events. What are Green Swans?

My idea for the Green Swan is that it arises out of a combination of Black Swan challenges with off-the-scale impact. While a Black Swan challenge delivers exponential problems, a Green Swan should deliver exponential progress in the form of economic, social and environmental value creation.

So we need to accelerate change exponentially?

Not just accelerate but accelerate the rate of acceleration. I once met Herman Kahn, the military strategist known for the nuclear strategy of mutually assured destruction. When I told him I believed climate change would be the biggest challenge of the future, he said, “The problem with you environmentalists is that you’re headed for a big chasm, and you think you can just slam on the brakes and steer away. Maybe you should be accelerating straight for the gap and see if you can make the jump.” Like an Evel Knievel stunt.

The older I get, the more I think Kahn had a point. Incremental change is no longer enough. Yes, I’d like to do it slowly and sensibly but that’s not how really big changes happen. Besides, we’ve run out of time.

Doesn’t that put business leaders in a bind?

Without a doubt. Danone’s CEO Emmanuel Faber is a case in point: He had embraced sustainability and was seen as something of a progressive among CEOs. But look at what happened to him: Activist funds started to attack Danone, saying Faber wasn’t paying enough attention to shareholders, and in March 2021 they pressured the board to remove him.

A colleague of mine who has been studying these matters finds that activists are targeting companies that have pronounced sustainability positions. This demonstrates that any CEO or business leader today has to hit multiple targets and achieve multiple forms of value simultaneously – and if they don’t, they’re going to be shot down. That’s a pretty uncomfortable position to be in, but no one ever said that CEOs were going to have a comfortable time of it.

Given that, why would anyone want to take on these sorts of challenges?

I share the feeling that right now it all seems too big and overwhelming. In a survey of MBA students about the world beyond 2030, most believed it was going to take a revolution of leadership, in business and politics, to break with the old order, and they feared we were entering a serious time of crisis to get there.

“The next 10-15 years will see creative destruction greater than anything any of us have experienced to date”

Which brings me back to Green Swans: Whether in nature – where you have what evolutionary biologists call “punctuated equilibrium,” long periods of stability punctuated by short periods of rapid change – or in economics – where you have waves of creative destruction – my sense is that the next 10-15 years will see waves of creative destruction which are off-the-scale greater than anything any of us have experienced to date, maybe since the Second World War. That’s not meant to be frightening; it’s just the reality that we’re going to have to cope with.

As such, our resilience – personally as well as in our organizations and supply chains – is going to be tested quite profoundly. But out of that will come very different solutions, better than anything we can imagine today. It’s worth noting that in the same survey of MBAs, most were hopeful that we would come out the other side; that achieving a more sustainable world was possible. And these are the business leaders of tomorrow.

If all signs indicate a profound shift is underway, why do some companies resist?

Partly because our brains are poorly designed to think of exponential trajectories. RethinkX (a thinktank dedicated to forecasting the speed and scale of tech-driven disruption) believes we are entering an exponential decade – or a “gradually, then suddenly” world, as Hemingway put it when one of his characters ended up bankrupt. Everything seems to be going along fine, until it suddenly isn’t, and this tends to happen with surprising swiftness.

I remember this happened in Japan during its financial crisis in the 1990s. Many leaders resigned because they didn’t understand what was going on – things were changing too fast. Today’s incumbents are in a similar death spiral, but they are yet to realize it or replace their old ways of thinking.

Even when they do try, mistakes are made, and not just with greenwashing. The wind power industry, for example, did not think through what to do with all their unrecyclable turbine blades. They should have thought about that earlier.

Is regulation the answer?

Only partly. Unless and until we also have the intelligence systems that really expose the good and the bad of what companies are doing, companies will game regulatory systems. They will produce reports or labels or packaging that just fit into the frameworks to get a suitably high – but sometimes misleading – score, without ever addressing the real problems.

Sometimes certification systems encourage our brains to go to sleep. That’s dangerous because in the next decade we’re going to have to think in extraordinary ways. It’s going to hit every sector, not just energy – sector after sector will be transformed.

“If we can share these stories and listen to each other, then we will create the learning journeys that we need to wake people up”

Are there positive signs of change?

Lots. At Volans, one of the areas we’re tracking is money and financial markets. There we’re seeing a change in the way economics is practiced and preached, which is immensely important, as many other systemic changes won’t happen without such a shift. Increasingly we’re seeing female economists such as Kate Raworth (Doughnut Economics) and Mariana Mazzucato proposing new approaches to valuing the wider world and putting the right price on things.

With respect for Milton Friedman, I think the era of Friedmanite economics is coming to an end, because the myopic pursuit of profit above all else is tearing our societies apart. When even the Financial Times has started to say capitalism is broken, we know we’re up for a reset. Walmart, believe it or not, recently committed to becoming regenerative, with a plan based directly on the work of the environmentalist Paul Hawken. The term regeneration is going to become central to the business agenda over the next few years.

I could give countless other examples – innovators like Azzam Alwash who has regenerated marshlands in Iraq destroyed under Saddam Hussein – which many people have never heard of, but whose stories need to be shared more widely.

Science fiction, too, is encouraging, if we want to think about where all this will take us. Writers such as Liu Cixin, David Brin and Kim Stanley Robinson are imagining what might happen if we start to address our problems in an appropriate way.

I believe if we can share these stories and learn to listen to each other – getting out more when the pandemic allows and meeting people who are quite different from us – then we will create the learning journeys that we need to wake people up. I am actually more optimistic than I have been for many years because we now have the opportunity to go faster, wider, deeper and, crucially, to go a different way.

John Elkington appeared during the 2021 IESE Global Alumni Reunion and participated in “The Future of Capitalism” course offered by IESE and Shizenkan University, whose next edition is scheduled for 2022.

The Blue Economy

03SustainAbilities

Serial entrepreneur Gunter Pauli believes too many green efforts by businesses to mitigate their impact on the environment are ethically insufficient: polluting less is still polluting, just like stealing less is still stealing. He came up with what he calls the Blue Economy, to stop doing less bad and start doing more good.

He founded ZERI (Zero Emissions Research and Initiatives), a global network of creative minds to come up with innovative solutions to the world’s problems, all inspired by nature. Many are shared in his book, The Blue Economy: 100 innovations, 10 years, 100 million jobs.

Here we highlight one case that captures the holistic nature of his vision. It starts with a cup of coffee.

Harvesting, processing, roasting and brewing coffee generates 99% biomass waste.

- Biomass waste emits millions of tons of methane gas.

- Methane gas contributes to global warming and climate change.

- Demand for mushrooms, especially Asian varieties like shiitake, is growing as consumer tastes and diets, particularly in the West, change in favor of healthier, vegetarian options.

- Many green efforts go as far as here – recycling waste, changing consumption habits – but that is only tackling part of the problem. The Blue Economy wants to scale up solutions at the global, not just personal, level.

Farming mushrooms on coffee is more energy efficient, and mushrooms sprout within 3 months after seeding as opposed to 9 months on natural hardwood.

- Leftovers after harvesting are enriched with amino acids and other nutrients from the process of being grown in coffee biomass. These leftovers can be fed to animals.

- The more people eat mushrooms and consume less meat, the less land needs to be cleared for raising livestock.

- The fewer animals, the less waste and methane gas.

- The less methane gas, the less global warming.

- The cellulose-waste business model, of which the coffee-mushroom one is a popular example, can become a new brand, where waste becomes a source of value creation.

This new model creates new jobs

In ethical new cafés and restaurants

- Cafés and restaurants serve this new coffee as well as new mushroom-based delicacies, with proceeds funding more entrepreneurial ventures in this vein.

In emerging markets where there are new growers, harvesters, farmers and producers

- Many of these new workers are women, who are empowered with new livelihoods, trained and given new personal and professional skills, helping them to become self-sufficient and escape poverty traps and associated social ills.

- This also contributes to food security, avoiding famine, disease, inequality, instability and conflict.

4 guiding principles of the Blue Economy

1. Be inspired by nature As in nature, think in terms of the entire ecosystem and its capacity to regenerate.

2. Change the rules Rather than zero-sum games, consider a system in which the commons are truly common (and therefore free) and where everyone is given a chance.

3. Focus locally Create value locally for reuse primarily locally, recirculating money locally and empowering local human resources, where everything and everyone is valuable.

4. Embrace change Build resilient systems that have the capacity to evolve.

Does it work?

The business model described here is already being employed around the world in various ways, for example: GRO, Equator Coffees, Back to the Roots (BTTR).

If this works for coffee and mushrooms, why not tea and apple orchards, or any number of other things?

Go to www.theblueeconomy.org and discover 100+ other cases of breakthrough business models that bring competitive products and services to market while simultaneously building social capital and enhancing mindful living in harmony with nature.

And if you would like to explore ways to put the Blue Economy philosophy into action, contact their think-and-do tank at info@theblueeconomy.org.

A case study on The Blue Economy (SM-1693-E) by IESE’s Mike Rosenberg and Jean-Baptiste de Harenne is available from www.iesepublishing.com.

Gunter Pauli spoke on “Building the Blue Economy” with Mike Rosenberg during the 2021 IESE Global Alumni Reunion in Madrid.

Enric Asuncion: “Sustainability is our engine of innovation”

04SustainAbilities

Enric Asuncion is the cofounder and CEO of the electric vehicle charging company Wallbox, whose shares now trade on the New York Stock Exchange. He spoke about high-impact entrepreneurship as part of IESE’s 2021 Global Alumni Reunion.

As charging stations gain ground, gas stations’ days may be numbered. Within five years, electric vehicles (EVs) will cost less to buy than fossil-fuel-powered ones, marking a turning point in the energy transition. This is the firm belief of Enric Asuncion, who, along with fellow engineer and longtime friend Eduard Castañeda, founded Wallbox in Barcelona in 2015 to prepare for an EV-filled future.

Since then, Wallbox has delivered innovative car-charging hardware (the wall-mounted boxes of their name) in over 80 countries, along with software and services to extend their reach to energy management.

In October 2021, Wallbox went public in a deal that valued the young company at more than $1.5 billion in trading. Wallbox currently employs more than 700 people on three continents and is looking to hire hundreds more as it continues its turbo- charged growth.

Here, Asuncion shares his vision in a world that is giving up gasoline to go green.

Why did you leave a job at Tesla to start Wallbox?

Six years ago, when I was at Tesla, there were hardly any EVs on the road. At that point, everyone seemed to be working on electric cars or public charging stations for them. But we knew that 80% of EV charging was happening at people’s homes.

We saw a business opportunity in home chargers: not only are they the most convenient way to power up, they can also offer consumers the cheapest and cleanest energy.

Eduard and I were talking about it at a wedding we both attended one weekend in 2015. We had always wanted to launch a project together, ever since we met at university, and right there and then we decided to create charging products to work with home power installations. I quit my job at Tesla on Monday.

The company has grown ever since. In November, Wallbox reported cumulative 2021 revenues of $55 million, 280% higher than the same period the year before. What do you think accounts for your success so far?

I would say two things. First, the people we have met as mentors, those who had been CEOs of companies in the sector, as well as those who know about all the things we didn’t know about as engineers, including marketing and finance. Finding the right people and listening to them at each step of our project has been key. If I had the team I have today at the beginning, we couldn’t have been as successful. And that’s true the other way around. It’s not that we’re getting rid of people; we’re moving talent around to be in the right place at the right time as we grow.

Second, I would say, is trying to be best and not the biggest company. To be a global leader in this space, we must know what is best for the company and try to do our best at all times. We have grown quickly and opened factories in Barcelona and in China, with another on the way in Texas to serve the U.S. market. However, our most important challenge is yet to come: We aim to hit $1.2 billion in revenue in 2025.

How do you hope to achieve that?

We believe we’ll be at the center of clean energy in the home. You see, when you buy an electric car, power consumption usually doubles at home. Energy management becomes very important.

“We genuinely feel that we have a very important role in the future of our planet”

Starting with our chargers and software, we enable users to collect power from the grid when it’s cheapest, perhaps overnight, and when it’s cleanest. In addition to charging, our solutions allow you to use your car battery to store power for your home. People may be surprised to hear that the energy stored in a single EV battery can power a house for up to four days if there’s a power cut.

Then, consumers who buy electric cars are three times more likely to install solar panels. Which is why the next version of our products connect directly to solar, optimizing the management of this renewable energy. We may also offer energy plans or enable peer-to-peer energy transactions. The energy transition is opening up many possibilities in energy management.

At the same time, we are expanding our catalog in commercial (semi-public) spaces and in public charging. The European Union has proposed an effective ban on fossil-fuel-run cars by 2035 and we want to take advantage of that.

How does your position in a sector that’s key to sustainability then translate into corporate strategy and its execution?

Wallbox helps customers make the transition to cleaner energy and make better use of it. At the same time, we try to lead by example: All our buildings and offices are solar-powered, with batteries for use at night. In constructing a new building, we follow the cradle-to-cradle concept, meaning that all materials are reusable and recyclable. To align our efforts at the product, policy and facilities levels, we’re creating a dedicated ESG/sustainability team.

Sustainability is the great engine of our innovation. It’s something I learned at Tesla: Everyone there was clear that the company had to succeed in order to make the world more sustainable. I have tried to bring that culture and sense of purpose to Wallbox.

When Wallbox went public via a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC), you became the first company in Spain, and one of the first in Europe, to go public this way. How does this process work? And would you do it again?

Absolutely! In early 2021, we saw that a couple of our international competitors were trying to go public. The beauty of going public is that you become transparent for all. By looking at these competitors’ filings with market regulators, I saw that Wallbox had more global reach, faster growth, better gross margins and more vertical integration, with our own factories and in-house design. It looked clear that we would win – but what we didn’t have was the extra $250 million that could be raised by going public. So, we pursued it.

For us, the best way to raise that much capital (over $200 million) and attract long-term investors at the same time was via the SPAC. The Kensington team (officially Kensington Capital Acquisition Corp. II) brought us people who understood our market and the need to think long term, as we think 97% of chargers have yet to be installed. Our sponsors at Kensington included the former CEOs of Chrysler, Lear and Thule, all experts in the automotive space.

Barcelona is one of the few places where you can hire engineers from anywhere in the world, make software and hardware, and have the suppliers to build factories; however, the access to capital is limited for startups.

So, we went where the capital is: the United States. It was an expensive process because, as you said, we were the first company in Spain to go public this way. There was a lot to learn, and I hope others copy us.

In the end, it was successful, and I would do it again. We genuinely feel that we have a very important role in the future of our planet. Our success is creating the products necessary for the energy transition.

Tackling sustainability

05SustainAbilities

CEOs are making their voices heard. And that’s no bad thing.

Milton Friedman may have died in 2006 but his shareholder primacy doctrine – that the sole purpose of the firm and its managers should be to maximize value for shareholders – remains alive, albeit on life support. Stakeholder capitalism is slowly taking over from shareholder capitalism.

This was a recurring theme in the dialogues we had with top executives and thought leaders at IESE’s Global Alumni Reunion in Madrid. Whether addressing climate change and ESG investing or inequality and poverty, it has become apparent to many that to run a sustainable business today, you can’t just prioritize the interests of a few shareholders; you also have to understand the needs of your many other stakeholders and make decisions that improve their welfare, too.

This shift toward stakeholder capitalism will not be easy. The sheer breadth of issues that corporations are increasingly being asked to be responsible for, and their technical complexity, represent formidable challenges for CEOs and top executives today.

To begin, corporate leaders will need to gain competence on the issues in order to understand how they may affect their strategies. In many industries, sustainability is challenging the dominant business models. Cosmetic changes aren’t enough and win-win solutions cannot always be found. A deeper rethinking of the firm’s purpose and strategy is needed, along with making some very courageous choices.

However, the bigger challenge is not technological, organizational or strategic – it’s political. Several years ago, my IESE colleague Bruno Cassiman and I suggested that CEOs would have to face three key challenges. The first two were well underway and obvious: globalization and digitization. The third, politicization, was just starting to emerge and remains far more controversial.

Noticing that the lines between public and private were blurring, and that large corporations wielded more economic, political and legal influence and power than ever before, we argued that CEOs would have to “recognize their roles as full-fledged political actors and assume the responsibilities that go along with that.” They would need to “step up and fully own their ‘politicized’ roles … in brokering relationships between competing stakeholder demands and unavoidable social responsibilities.”

This politicization is precisely what worried Milton Friedman in his famous 1970 New York Times essay in defense of shareholder value against the many voices that were suggesting business had a social responsibility. Had Friedman heard the CEOs of our recent conference, he likely would have denounced them as “unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of a free society,” insisting they leave environmental and social concerns to elected officials. He feared that “the doctrine of ‘social responsibility’ taken seriously would extend the scope of the political mechanism to every human activity.”

On that last point, I cannot disagree. But I would question whether that is such a bad thing. (It’s worth noting that Friedman viewed social responsibility as a slippery slope toward communism, which, given all that has transpired over the past 50 years, seems an exaggeration.)

Corporations have always been doing politics. The difference now is that they are expected to do it not in the shadows but out in the light

The problem with Friedman’s argument is that, on the one hand, it assumes that corporations and corporate leaders were not doing anything remotely political before they were asked to consider their social responsibilities; and, on the other hand, it limits political mechanisms to the workings of parliamentary democracy.

According to Friedman, then, for-profit media organizations (and social media platforms) do not do politics, despite their obvious influence (some might say control) on public opinion. In reality, corporations, especially large multinationals, have always been doing politics. They were doing it primarily to advance and protect their own interests and those of their shareholders. And they were doing it in the shadows, primarily through backdoor lobbying.

The difference now is that they are increasingly expected to do it more transparently, out in the light, in conversation with societal actors but always under democratic oversight.

We must not be naïve to the dangers of leaving important political decisions to corporate CEOs. Still, it’s better to have them involved in the critical conversations we need to have about the global challenges we face – and the possible solutions – rather than banish them from the public arena. After all, their real-world power and influence won’t be any less, only less visible.

As such, when it comes to sustainability and stakeholder capitalism, I welcome CEOs’ social and political engagement, and I prefer to be optimistic about the role they can play in helping us build a better society for all.

Fabrizio Ferraro is head of the Strategic Management Department and Academic Director of the Sustainable Leadership Initiative at IESE.

This Report forms part of the magazine IESE Business School Insight #160. See the full Table of Contents.

This content is exclusively for individual use. If you wish to use any of this material for academic or teaching purposes, please go to IESE Publishing where you can obtain a special PDF version of this report as well as the full magazine in which it appears.