Tech at a turning point

01Tech at a turning point

This year, for the first time, more people in the world will be online than off. Yes, the 50/50 line was finally crossed, connecting nearly four billion of us around the globe. The year 2019 also marks the launch of 5G, the biggest upgrade to cellular networks in a decade, promising a level of digital services previously unachievable. And the World Wide Web just turned 30 years old: virtual adulthood reached.

Yet, for all the benefits, new problems are arising at an alarming rate. “Techlash” is now a thing. Data breaches, fake news and cyberattacks are everyday threats.

What can we do better to meet the challenges of the web’s next 30 years?

And consider how the web’s power players have consolidated. Alphabet (Google), Amazon and Facebook all recently reported record profits. In early 2019, they were worth a collective $2 trillion, more than most nations’ GDPs.

In the Fourth Industrial Revolution, we have arrived at a pivotal point. In 2019, there’s a new reality that business leaders must reckon with as they continue their digital journeys. If data is the new oil (or the new air, as DBS Bank CEO Piyush Gupta described it to IESE Dean Franz Heukamp) what is at risk in its pursuit? Are we in danger of turning people against what was once thought to be a great equalizer, a conduit of real information, a beacon of democracy?

At one of the world’s largest tech gatherings, the Web Summit, held in Lisbon in November 2018, 70,000 participants from 170 countries grappled with tough questions regarding our digital future. Various members of IESE’s faculty participated, speaking to tech-optimistic entrepreneurs and executives on what we can do better to meet the challenges of the web’s next 30 years.

While there are no easy answers to the lofty questions raised, the business leaders of tomorrow clearly must acknowledge citizens’ digital rights, along with the true impact of technological change.

“I used to say data is the new oil. I’ve now changed. I call data the new air, because oil you can control, while air you can’t.”

Piyush Gupta

The CEO of DBS Bank argues that, given the democratized nature of data, we need new social rules where use of data is driven by context and use as opposed to notice and consent.

Bridge the digital divide

The inventor of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee, says the most crucial aspect of the web to preserve is its universality. In bringing it to life back in 1989, he recalls “it had to work with any language, any hardware, any software, and it had to be open and free” – the original net neutrality.

Its first 15 years, as Berners-Lee describes it, were incredibly optimistic, connecting people with technology – blogs, Wikipedia, Skype calls – to make great things happen. But the next 15 years were more problematic, with privacy abuses, misuse of personal data, and “fake communities of fake people with fake views” dominating the recent past.

Why does this matter? The short answer: at this 50/50 moment, a digital divide is quietly widening. Earlier projections about connecting the world’s poor, especially poorer women, have proved overly optimistic. Online growth rates, especially in the past three years, have slowed.

A digital divide is quietly widening. Online growth rates have slowed.

Now we have two problems, says Berners-Lee: getting the other half of the world online while making sure that “the next billion connect to a web worth having,” a place that’s better than what we have today.

As such, Berners-Lee has announced an ambitious “contract for the Web,” a manifesto to make the web more “safe, accessible, diverse and open.” France was the first country to sign on; Germany is another early backer. Government reps, tech companies (including Google) and prominent stakeholders in civil society are busy hammering out the details in working groups. For example, one working group is seeking “commitments from government and the private sector to achieve affordable access, connectivity and accessibility standards online” while another is outlining “steps that governments and companies can take to ensure privacy is respected.”

Will the United States cooperate? Will China? What role should the private sector play in this? There are still so many open questions. Yet, whether the contract achieves its aim of “trying to make the web a better place” for everyone, the issues it raises and the impetus behind it remain highly relevant to business. Expect to hear more about this in the year ahead.

Prioritize privacy concerns

The most oft-repeated abbreviation at the summit, after AI, was GDPR, the General Data Protection Regulation of the EU, which marked the most significant change in data privacy regulation in decades, affecting companies around the globe if they handle European citizens’ data. More than “just a regulation in Europe,” for Berners-Lee it represents a sea change in “the global conversation about privacy.”

European Competition Commissioner Margrethe Vestager, arguably one of the most powerful politicians in the tech world, echoes this sentiment about privacy and data rights. Her office is famous for fining Apple, Google and Amazon to the tune of billions in the name of just and competitive practices, online as well as off. Her main message is that the right rules can help fix what currently ails the web. She notes that, in our homes, electricity is risky; it can kill us. But we don’t fear our homes, thanks to good regulations that are being followed.

“If we can regulate nuclear power, why can’t we regulate some code?” asks Chris Wylie, the whistleblower who revealed that the U.K. political consulting firm, Cambridge Analytica, had developed profiles of Facebook users (using data obtained without their consent) deemed most likely to spread fake news. Fake-news spreaders were then manipulated in 2016’s Brexit referendum and the U.S. election of Donald Trump.

Wylie says he has been deeply worried by the level of discussion coming out of the United States, with one congress person asking him, “Where in America do we store the internet?” If these are the people responsible for developing the relevant regulations, he says, this doesn’t inspire much confidence.

“If we can regulate nuclear power, why can’t we regulate some code?”

Chris Wylie

The Cambridge Analytica whistleblower has been deeply worried by the level of discussion coming out of the United States, which he says does not inspire much confidence.

The growing consensus among the experts seems to be that more oversight is imminent. The question is: how to do it well? Early indications suggest that Europe’s GDPR, years in the making and now over a year in practice, could serve as a global standard for data privacy protection. Companies are learning how to work with GDPR and that knowledge should help shape what’s next.

See the big picture

As the digital and physical worlds continue to blend (or collide), IESE’s Javier Zamora insists there are emerging opportunities in such “digital density.” Managers should keep a close eye on the internet of things (IoT), blockchain and even quantum computing. Luckily, managers don’t need to be experts in qubits or distributed ledgers; they just need to know what, generally, the next threats and opportunities are. He recommends making tech media such as Wired and TechCrunch.com part of your daily reading. “And take an aspirin with that,” he jokes, because the endless possibilities you read about will make your head hurt.

“In our homes, electricity is risky. But we don’t fear our homes, thanks to good regulations that are being followed.”

Margrethe Vestager

The European Competition Commissioner, famous for fining Apple, Google and Amazon in the name of just and competitive practices, believes the right rules can help fix what currently ails the web.

After the aspirin kicks in, step back to consider the big picture. Consider what is happening, why it is happening, and how to adapt to maximize value in your company while minimizing the challenges. Zamora cites BBVA to explain the business model implications of connected data, as digitalization opens traditional businesses up to new competitors and new opportunities, even partnering with potential competitors. Of course, these partnerships present challenges. Integration works best when there are widely shared standards and application program interfaces (APIs), which allow apps to share data and work together.

Anticipate shifts & impacts

For all the promise of IoT, the lion’s share of “meaningful and valuable” data still comes from people and organizations, not things, Zamora points out. Which brings us back to privacy concerns: transparency and trust are paramount.

IESE’s Sandra Sieber, predicting the top trends for 2019, uses healthcare as an example: if a drug is prescribed, the patient’s pharmacy could communicate directly with the drug’s manufacturer and get a car service to deliver the prescription to the customer’s home. If the relevant organizations’ technology architectures were such that all the necessary data could be shared, then building new service offerings with new partners, like the one just described, would be possible. Connected data would move to B2B2B2C. But, Sieber stresses, “ultimately that C (the consumer) is the owner of their data.” And that consumer should have the right to move their data from one service provider to the next.

The consumer should have the right to move their data from one service provider to the next.

With business models and responsibilities shifting like this, an important exercise for managers is to ask themselves: what will their company look like as digital density inevitably increases, and in what ways will their value propositions grow ever more complex?

Keep learning

More complexity necessitates new and constant learning. In agreement with Zamora, IESE Dean Franz Heukamp emphasizes that, “Today’s business leaders must know enough about technology to know what’s possible, what’s being impacted, and how it affects their business model.” With change now “the normal state of affairs,” leaders need to learn how to be sharp decision-makers with “good judgment,” able to “handle change in their organizational architecture and in their business models.”

“We see that the implementation of digital strategies has a lot to do with the implementation of organizational change. And that, of course, has a lot to do with people,” says Heukamp. “If you have the right people, and you manage them well, you will be able to implement your strategy,” working to provide “new things that are better than what they are replacing.”

This emphasis on continuous learning is echoed by U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres. With new technologies come disruption and a consequent impact on social cohesion. “It’s clear we aren’t prepared for that, and we’re not preparing fast enough for that,” he warns. “We will need a massive investment in education, but a different sort of education.” What matters now is not learning “things” but learning “how to learn things.”

“We are in a world full of opportunities, thanks to technology. Our purpose is to bring the age of opportunity to everyone.”

Carlos Torres Vila

The CEO of BBVA asserts that incumbent banks are very well positioned to be not just money banks, but also trusted “data banks” in the future.

Learn outside the box

The need for “a different sort of education” is also one of the takeaways of a recent IESE study in Spain. According to the Education for Jobs Initiative, most (72 percent) of the 53 large firms surveyed say the digital revolution has had a high or very high impact on the profile of workers needed. Yet up-to-date know-how in job candidates is lacking: 68 percent of companies surveyed note an important knowledge gap in technology and digitalization among university graduates and 48 percent see that gap in vocational training graduates. Looking ahead five years, survey respondents believe knowledge gaps will widen further in areas such as big data, digital marketing, artificial intelligence and blockchain. Spanish education needs to be more responsive to labor market needs, suggests the report. On a practical level, that may include more vocational training and boot camps to learn skills like coding.

On an enterprise level, can large companies learn in a different way? Yes, according to other IESE research released at MWC Barcelona (formerly Mobile World Congress) in February 2019. Julia Prats and her coauthors studied corporate venturing, a collaborative framework for established companies to work with startups in the pursuit of innovation. By using certain mechanisms such as scouting missions, challenge prizes, hackathons, corporate venture capital and acquisitions, big companies are able to spark innovation and bring innovative ways of working into the fold.

On a scale of 1-10, rate your digital maturity

0 We’ve got some work to do!

2.5 We’re digitally aware

5 We’re adopting digital methods and practices

7.5 We’re a digitally enabled business

10 We’re a digital pure play

With regard to people management, digital transformation favors emotional intelligence and non-hierarchical leadership. To this end, IESE’s Carlos Rodriguez-Lluesma, in line with Prats’ report, recommends adopting agile principles – flatter structures, delegated authorities, freedom to test new ideas, a bias toward action – and creative methodologies such as design thinking and scrum. This has implications for hiring decisions and ongoing training. Recognizing there is a digital divide, even within companies, managers must promote continuous learning, so no one is left behind.

How? Specifically, Rodriguez-Lluesma lists:

- Train your workforce in digital skills (reskilling).

- Set up learning hubs and innovation communities.

- Coach management on digital strategy and on building a personal brand on social media.

- Practice reverse mentoring, whereby younger professionals help senior executives stay abreast of the latest trends.

With the web’s 50/50 moment upon us, and more uncertainty the only certainty for the near future, reckoning with digital transformation means opening up to new ways to manage, learn and innovate. All that while making sure your customers’ trust is never breached.

Buzzword: techlash

At the end of 2018, Financial Times’ Rana Foroohar chose “techlash” for “the year in a word” column. “Techlash is the predictable result of an industry that can’t govern itself,” she wrote. “No wonder even insiders, such as Apple’s Tim Cook, are now calling for the sector to be regulated.”

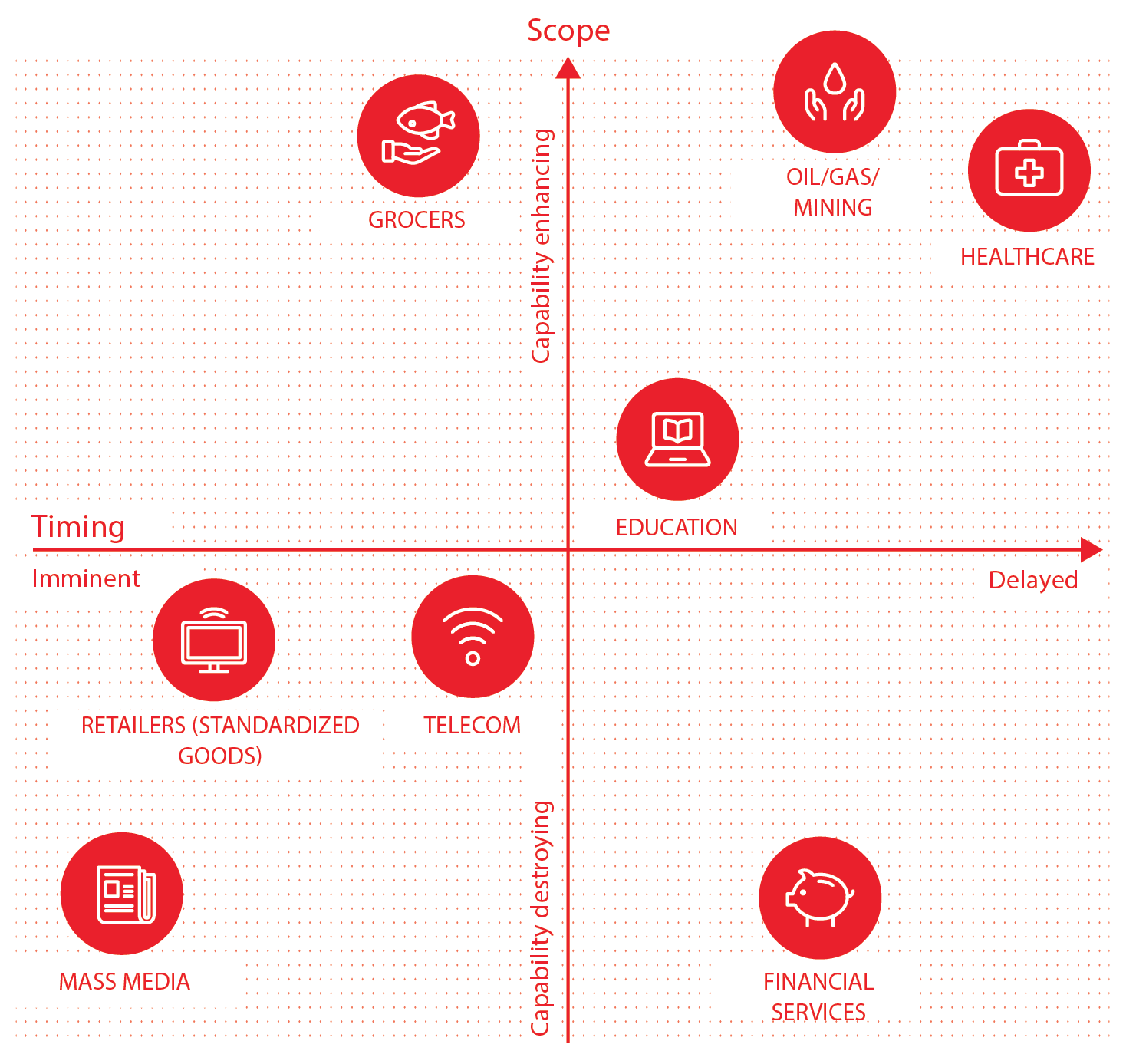

How will digitalization affect your sector?

02Tech at a turning point

Where are you positioned?

New technologies can enhance or destroy your business proposition, either sooner or later. Use this matrix to reflect on the scope and timing of the impact of tech on your sector.

Principal impact factors

Given the dynamic nature of tech, the position of any one sector is not fixed but will constantly evolve over time. Various factors will influence that evolution, but here are four key ones whose interplay may provoke a shift.

1. Ease of digitization

How easy is it for your product or service to go from being “atoms” (physical) to “bits” (virtual)?

2. Proximity to consumer

How much power does the consumer have to dictate your terms of service? The more democratized your value chain, the faster and more disruptive the shift.

3. Degree of regulation

How regulated is your sector? The more heavily regulated, the longer it will take to change.

4. Requirement of CAPEX

How much capital do you need to invest up front? A CAPEX-intensive industry, like mining, means its disruption will be much more difficult.

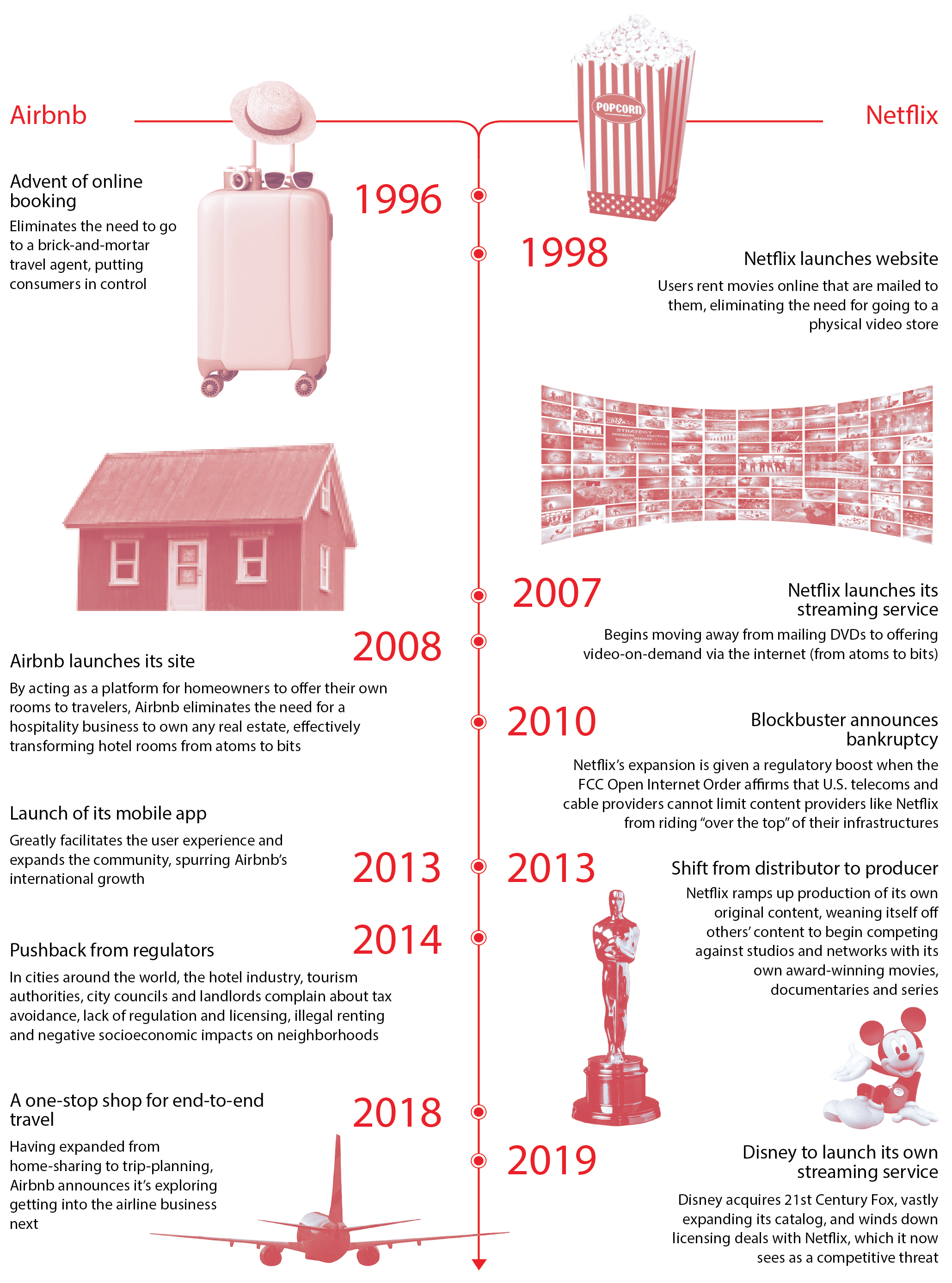

Airbnb and Netflix: a timeline of digital disruption

The evolution of these two well-known companies shows how the four impact factors can influence a business to go in different directions.

Mark Thompson: “Any transformation needs transformational leaders”

03Tech at a turning point

No matter what kind of company you work for, you’re probably grappling with a common challenge: taking the enterprise you’ve inherited and deciding what to keep, what to add and what to throw away. How do you run the legacy business and the new business simultaneously? And how do you do it without the past and present suffocating the future?

“For managers trying to figure that out, this is where the medals get won,” says Mark Thompson, President and CEO of The New York Times Co., which had over 160 years of history behind it when he joined in 2012. It was a pivotal moment, as the paper had recently implemented a paywall when it wasn’t clear whether paywalls would stem or speed the decline of print media. All that was known was that something had to be done to respond to the digital disruption that was upending traditional business models.

Seven years later, the Times’ gutsy gamble appears to have paid off. It was the first news organization in the world to pass the million digital-only subscription mark, and some of its new digital experiments, such as its podcast, “The Daily,” are winning those awards that Thompson talked about.

“Now we’re trying to prove that it’s possible to scale a subscription- based news business in the way that Spotify, Netflix and others in the music and entertainment business are proving scalability there,” he says.

Here he discusses the keys for maintaining the quality of your offer while making your digital transformation sustainable.

What was the situation like when you joined?

It was like every other company on the planet: they wanted change. The paywall decision had been made before I got there. There were a lot of people, maybe even half the company, including half the leadership, who were worried (1) that there’d be no demand for subscriptions and (2) that the Times was betraying an idea of the open internet by putting up a paywall. But they made the decision on the basis that the opportunity was a relatively small one. Originally they thought they might pick up 200,000 digital subscriptions. At the very peak of the print business in the ’90s, the Times had about 1.8 million subscribers. Now we have 4 million. And the majority of those are digital.

Being British, to what extent do you think being an outsider helped?

I think being an outsider is quite useful. So is being an optimist. That can-do spirit of believing in the future needed to be awakened. Once people had been given permission to think big about what could be done, suddenly the really crazy ideas started coming.

What kind of executive do you look for?

Any transformation needs transformational leaders. Most of the hard work of transformation is not done by chief executives. The chief executive needs to create the space and maybe set a broad direction, but it’s going to be, in military terms, one-star or two-star brigadiers and three-star generals who are actually going to fight the battles and get the job done. My model is: find really able people and then not get in their way.

Although the paywall model seems to be successful, critics say it could have a polarizing effect: those who pay get access to quality, while those who don’t pay end up with fake news. Is that a concern?

I would say we’ve got not a paywall but a pay model. In a typical month, we have around 140 million unique users worldwide, of which 4 million are paid subscribers. That means we let about 136 million people every month read our content without paying. We keep it porous. When there are national emergencies or big elections, we often take down our paywall entirely. We want to make sure we are distributing our content very broadly, so that almost anyone who wants to sample our content can do so without paying. The hope is they’ll fall in love with it and, when they can pay, they’ll start paying.

How and when do you, as a leader, make that difficult decision of pulling the plug on something that still seems to be working but you know has an expiry date?

It’s an economic decision but one very much based on how customers value your product.

As the demand for print falls, you’ll begin to experience the negative economics of unwinding economies of scale. You can put in regular price rises so that the revenue from subscribers declines at a slower rate. But as your number of copies declines, print advertising goes away and, even with price rises, the unit costs go up. At what point does the per unit cost of manufacturing and delivery, and the per unit revenue delivered, essentially cross?

The economics could steady, where it could make sense for indefinite print-platform continuation. But we’re planning our future on the basis that there will be a crossover, at which point we will stop printing.

In some ways, it will be in the collective choice of our users at what point the prices become too much for them.

“A world in transition needs thoughtful, intelligent people.”

How do you make sure the legacy platform doesn’t overwhelm or distract you from building the platforms of the future?

I think we’ve solved that problem. We’re a digital newsroom where we have multiple different ways of expressing our journalism – websites, smartphones, podcasts, live events, a TV show – and print just becomes another platform for what we do. And it’s likely that one day it’s not going to be with us. So, let’s treat it as that. You’re crucially never going to allow a print consideration to stop you from doing what you need to do in digital – simple as that.

I think software-as-a-service and the idea of paying a regular fee for access to cloud-based services of every kind is transforming both B2B and B2C. Netflix is an obvious example.

At the New York Times Co., we’re trying to create an engine of growth where we get better and better at the tactics of growing a digital subscription business. The success of that business enables us to invest even more in content.

We’re trying to break the downward spiral which news is facing across the Western world and get into a virtuous upward spiral. There’s no reason why we cannot be bigger, better and, ultimately, more profitable after the age of print.

We’ve now got a path for creating a great news organization that doesn’t depend on print if the economics go as I think they probably will. That’s the key.

“The Daily” podcast is a good example of one of these new activities. It used to be assumed there was no market for serious speech radio among young people – that they only wanted to listen to music. Yet “The Daily” is demonstrating otherwise.

The audiences of today – not just young people, but all audiences – want to get a sense of “who is telling me this.” The Times has always stood for authoritative, quality journalism, which of course we want to keep, but the editing process was designed to take the personality out and standardize the voice of the Times. We’ve done a 180-degree turn on that.

The podcast enables this humanizing, personal experience. To me, it’s an example of a platform which emotionally broadens the tone of the Times. I think that business of heart, as well as head, can be a way of attracting a wider audience.

If the fundamental task is to engage and form a deep relationship with an ever bigger global audience, having multiple different ways of doing that, and using each kind of medium for what it’s best at, makes good strategic sense.

Our experience shows there is, in fact, a massively underserved market for engaging, emotionally authentic, true speech radio for people under the age of 30.

To what extent is your industry actually thriving on all this disruption?

Our world is transforming in unknowable, complex ways, and with all sorts of puzzling issues for business, for government, for society, for industries. There are enormous challenges like globalization, automation, climate change and inequality. That sense of a world in transition, where we don’t quite know what the destination is, is a world which needs thoughtful, intelligent people.

You could say it’s a great commercial opportunity, but the real point is, the societal need for our profession has never been greater.

Toolkit for tomorrow’s executives

04Tech at a turning point

Can you let your employees bypass IT?

06Tech at a turning point

When innovators in your organization are working around the IT department, something is wrong. Take it as a sign that your organization has to change, and use it as an opportunity for digital transformation.

Here are five tips for taking a creative approach to IT that can ultimately transform IT anxiety into agility.

1. Find a work-around

Sometimes, to keep pace with your market, working around your IT department may be necessary. For firms established under different market conditions, bypassing legacy IT can help ensure ongoing learning and adaptation to evolving customer expectations.

I’ve witnessed this in a major global bank with IT policies and standards dating as far back as the ’70s. By allowing certain units to work directly with customers and fintechs, the bank began creating an ecosystem of new services, eventually leading to a bottom-up transformation in IT governance.

2. Insulate and empower bypassing teams

Shield bypassing teams from organizational policies and rules. Invest in them financially. Give them leeway and independence. Locate them in a different area, so they don’t interact with other units too much. Let them be speedboats while others move more slowly.

Bear in mind this might cause culture clashes. Managers need to watch short- and long-term goals, so any tensions don’t pull the organization apart.

3. Scale up innovations by linking them back to the core

Once you have a prototype, it needs to be linked to core processes and other complementary products; if not, the customer experience will suffer, and so will your operations. An innovative app, for instance, may be created autonomously, but it must be plugged into the common digital platform via APIs to ensure interoperability and integration with other apps for a seamless end-to-end customer experience.

Innovations shouldn’t be 100% new: autonomous teams should reuse as much existing technology and API-exposed functionalities as possible. If that’s not happening, that’s a red flag.

4. Be guided by the shared purpose to serve the connected customer

Moving away from a hierarchical model to a distributed, networked one means not everything needs to be reviewed from above, yet the company remains legally and ethically responsible for the handling of data.

As such, a common mission is key to guide autonomous teams to do the right thing. Managers must check in on their digital initiatives to ensure they are serving the broader purpose and fitting with the mission to serve the connected customer.

5. Take bypassing as a sign of dysfunction

If you can’t work with your IT department as it currently stands, there’s a misalignment somewhere that must be fixed. Is your current governance too rigid? Do you need a distributed, platform-based architecture for more agility?

In this sense, bypassing IT may treat the symptoms, but not cure the disease.

Look for the cure in digital transformation

To find your cure, identify a viable pathway of transformation. In the case of the global bank I studied, it shifted to cloud computing and provided workers with access to digital services through a self-service platform. Employees (not just IT staff) could easily and directly access a catalog of services and recombine them as they developed personalized yet scalable solutions for their customers. This enabled the bank to serve the connected customer anytime, anywhere.

Think about transforming the tech layer of your organization, and connect it to transformations of structure (new product development) and strategy (business model innovation). Doing so can trigger profound changes.

Robert Wayne Gregory is an assistant professor of Information Systems at IESE. In 2016, he received the Early Career Award from the Association for Information Systems for his research on digital transformation.

For more on this story, read “The iPhone effect: consumer pressure transforming IT governance.”