Artificial intelligence, real leadership

01Artificial intelligence, real leadership

Will artificial intelligence force us to rethink business in the decades to come, or will it fall short of all the hype? Here, a look at what executives need to know.

As artificial intelligence (AI) expands the boundaries of what computers are capable of, it also puts new demands on executives to understand these evolving technologies, to find practical applications for them in their companies, and to resolve the unique ethical dilemmas arising from machines with ever more human qualities.

For many, it’s a whole new world. While artificial intelligence may come to define business transformation in the 21st century, most people are unable to describe what AI actually is, or to gauge its potential impact on their companies and society.

The most relevant competency for managers is to know what’s possible

“AI is the new IT. It means lots of different things to different people,” says Dario Gil, vice president for AI and quantum computing at IBM. AI in its most straightforward definition means the demonstration of intelligence by machines. The AI field includes machine learning, neural networks and deep learning. But AI has also become an umbrella term for many other related subjects, including big data.

“AI now is what Marvin Minsky, co-founder of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s AI laboratory, used to call a ‘suitcase word,’ in the sense that it contains many different meanings. We need to move from this to the specifics,” says IESE professor Javier Zamora.

AI and its impact on management have been the focus of a number of forums at IESE in recent months, gathering industry executives and academics to consider what it all means for the future.

Six decades of stops and starts

While companies are investing more in AI than ever before, it is not a new concept. Artificial intelligence was founded as an academic discipline in 1956, and business felt the first tremors of this seismic shift in technology in the 1950s, when early computers gave retailers the power to collate sales data on an unprecedented scale.

But AI has historically struggled to find practical applications that live up to its promise. It did not work well enough to be useful for most companies until the last 10 years or so, when lower-cost computational power and more sophisticated algorithms intersected with the vast data sets that could be harvested from the internet and other sources.

“What made possible the recent successes of artificial intelligence and deep learning are basically two ingredients that were missing some years ago: access at relatively low cost to very high performance computing and of course the availability of lots of data,” says Ramon Lopez de Mantaras, director of the Artificial Intelligence Research Institute at the Spanish National Research Council. “The concepts have been around for a long time. But actually AI right now is still in its infancy.”

Nonetheless, some are beginning to view AI as a so-called general purpose technology, capable of transforming broad sectors of the economy, on par with developments such as the steam engine, electricity and the internet. Beyond the large high-tech companies that have been early adopters, today AI is penetrating the automotive, telecommunications and finance sectors. It is being used in retail and the media, and is seen as having enormous potential in areas such as healthcare and education.

Virtual assistants like Siri, Google Assistant and Alexa are some of the user-friendly forms of AI

Julian Birkinshaw, a professor at London Business School, describes the growing ubiquity of AI by using the analogy of living in a mountainous world and watching the waters gradually rising. At present, he says, AI is about making existing processes more efficient. We believe that we are on safe ground — that there are tasks only humans can do, requiring cognitive insights that AI will never reach. But he cautions against complacency. “The future,” he says, “will be very different.”

Our own cultural attitudes may determine the success of this adaptation. Tomo Noda, founder of Shizenkan University in Japan, points out that Japanese media frequently depict AI as friendly and here to help us, citing Doraemon and Astroboy as examples. He contrasts that with the dystopian visions presented by Hollywood in movies such as AI, 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Terminator. Noda urges us to reframe our engagement with the new technology by asking more positive questions: Can we do what we do better with AI? What new opportunities can we explore? How can we create a desirable society together with AI?

From narrow to general and back

Current AI technology is “narrow,” capable of working at superhuman speed on specific tasks in specific domains — such as language translation, speech transcription, object detection and face recognition — given good enough data. But we are already on the path to “broad” AI, which will be highly disruptive.

To “teach” the algorithms that AI uses, humans still often need to label the first data sets themselves (for example, by identifying objects in photos). This is an expensive process and, as a consequence, most organizations don’t have enough labeled data. That is one of the reasons that many of the companies which have incorporated AI into their core businesses have been large digital natives such as Google and Amazon.

Broad AI will be able to transfer some learning across networks, or use reason to create its own labels, thus learning more from less data. Narrow AI needs a new neural network for each task but broad AI will multitask across multiple domains.

Beyond broad AI, “general” AI, with full cross-domain learning and autonomous reasoning, will be truly revolutionary. But machines capable of reasoning and understanding in the way that humans do are decades away, and fears of “singularity” — the moment when AI surpasses human intelligence and evolves beyond our control — are premature. Still, those concerns will one day have to be addressed.

New management competencies

Even narrow AI requires new knowledge and abilities of management. Studies have shown that AI is most successfully deployed in companies where it is prioritized by the highest-level executives. Executives must have a basic understanding of data and its potential uses, to have a sense of which tasks are best handled by AI and which are best left to humans, and of how to enable their teams with these new technologies.

That is not to say that executives must be data scientists or computer programmers. But they do need to be able to ask the right questions. “The most relevant competency for managers is to know what’s possible,” says INSEAD Dean Ilian Mihov. “Algorithms will find patterns in the data but they can’t interpret them. Managers have to think about what might be happening; then, ask themselves how they can create an experiment to test if it’s true.”

For IESE’s Zamora, putting AI into practice begins with a series of basic questions that executives must ask themselves: Is AI relevant to the problem that I’m dealing with? Do I have enough high-quality data to train the system to produce solutions? Are there tools such as software and algorithms available that can be applied to this problem? Can I trust the results of the algorithms?

Data readiness must go beyond the management level. Creating a data-fluent corporate culture is essential. Nico Rose, vice president of employer branding and talent acquisition at Bertelsmann, recounts how his company hired brilliant data scientists from big tech companies to implement advanced AI solutions. But they had little success. Switching tack, Bertelsmann began focusing on building an organizational ecosystem that supports data readiness. Hiring is part of that, but so is continuous education and learning for all employees.

Today’s university students face the prospect of forging their entire careers amid the changes that AI will bring — and they need to be prepared. Over 1,000 Stanford students enrolled in an introduction to machine learning class this past academic year. Professor Jeffrey Pfeffer explains: “They don’t want to be computer scientists; they just know it’s an important tool for everything.”

The humans in the mix

There are also limits. Wharton’s Peter Cappelli calls the corporate world’s new obsession with data “the revenge of the engineers.” He says that management is partly to blame for this in areas such as human resources because it has developed so many theories that have failed. But rather than turn people divisions over to data scientists, executives should reconsider how they manage, evaluate and motivate people.

There is a huge need to go back to some of the more social, human sciences

For the World Economic Forum’s Anne Marie Engtoft Larsen, those skills are not all about technology. “I think there is a huge need for us to go back to some of these more social, human sciences, such as complex problem-solving, critical thinking, creativity, people management, coordination with others and emotional intelligence.”

Executives should reflect on what they do best and focus on how their strengths differ from those of AI. There are some areas of strategic decision-making where humans will always have an advantage. These includes injecting creativity, originality and emotion into issues, and making concessions. The most insightful strategies, LBS’s Birkinshaw asserts, are often taken from metaphors from very different spheres. “That’s a very human quality,” he says, “to see a pattern in something unrelated and link it back to the world in which we’re working. I can’t see how computers could do that.”

He believes it is worthwhile to go back to basics and ask: What is a strategy? Citing American professor and author Michael Porter, he defines strategy in two dimensions: as choices that lead to actions, and — in the case of successful strategies — as being differentiated. A good strategy, in other words, is different from that of one’s competitors.

If companies rely on similar data sources and algorithms for AI-supported strategic decision-making, differentiation could be lost. Purely quantitative decisions can be too sterile; emotional conviction still adds value.

Thoughts from around the globe

Anne Marie Engtoft Larsen, World Economic Forum “We need to have a discussion around what values are going to guide how we develop these technologies”

Tomo Noda, Shizenkan University “Without defining values we cannot deal effectively with problem solving”

Dominique Hanssens, University of California, Los Angeles “If you look at the evidence of what creates long-term value for the firm, it is customer asset building and brand asset building, which require that holistic view. And so far, I have never seen a computer build a brand”

“Planning, budgeting and organizing can be done by AI,” says Shizenkan’s Noda. “But establishing vision, aligning people and motivating them requires people.”

Executives also must reflect on why firms exist, in order to clarify their own roles within them in a changing AI world. A key reason is to craft a sense of identity or purpose. Successful companies understand this and know who they are. A second reason firms exist is because they are good at managing complex tradeoffs, even over time and in the face of shareholder pressure. AI is not good at this and is unlikely to become so. Nor is it good at building processes for reconciling diverse points of view.

Bringing ethics to the table

AI raises the specter of machines that we create but that may one day surpass us, of computers that we program but that may make decisions we do not fully understand, of robots that assist us but that may make mistakes. All of this generates a host of new ethical quandaries, particularly around issues of fairness, accountability and transparency.

The fairness debate, in part, centers on the danger of perpetuating biases. While data sets are ostensibly objective, they actually reflect ingrained biases and prejudices. If data is then fed into algorithms, how can we ensure that those biases are not embedded into the future?

Accountability has to do with deciding who is ultimately responsible for systems, particularly when something goes wrong. As machines become more autonomous, there are increasing questions about where responsibility lies among those who design and deploy the systems, and the systems themselves. Who is responsible if a cognitive machine takes the wrong decision?

Transparency and explainability become issues as AI-assisted decisions become less easy to understand. How can decisions be interpreted and understood if we don’t understand how they were arrived at? As AI algorithms become so complex that even their authors don’t fully understand them, how can we explain and justify the decisions they make?

These are unique dilemmas, although ethicists also warn against exceptionalism in the AI debate. Previous ethical debates, such as those surrounding medicine or nuclear energy, have much to contribute to the conversation.

AI over time

First wave: mid 1950s to early 1970s Term “artificial intelligence” used for first time in 1956, amid a surge in interest in this new field

Second wave: mid 1980s Government funding and AI programs with practical applications spark renewed interest in AI

Third wave: mid 1990s to present More powerful computers, better algorithms and more data cause AI to flourish

For most companies, the ethical questions will relate more to AI’s application than its technological development. Even narrow AI is affecting society at large, rapidly making some jobs and industries obsolete while creating new ones, which require completely new skill sets.

While businesses adapt to the AI-fueled Fourth Industrial Revolution, millions of people around the world have failed to benefit from the advances of the First, the Second, or the Third.

The implications of AI go well beyond the business sphere, involving policymakers and governments. Stanford’s Pfeffer believes that governments lack the skills they need to manage the employment changes that AI will bring. “Advanced, industrialized countries have done a bad job of managing the move from manufacturing to services,” he says. “They will struggle here too, especially with ageing and sometimes shrinking populations, budget deficits and rising social costs for healthcare. How are they going to find the resources to re-skill or upskill large numbers of people?” Reflecting on the possible political and social implications, he adds: “We have to do better this time.”

Business leaders in the AI era will need to consider how their use of technology affects society. They will need to think of the human consequences and ethical dimensions of their AI-derived decision-making. And ultimately they will have to manage businesses by relying on what sets them apart from machines.

Competitive advantage in an AI world

By Bruno Cassiman, Professor of Strategic Management and holder of the Nissan Chair of Corporate Strategy and International Competitiveness at IESE

Strategy is not immune to the wave of change brought on by AI.

In the short term, companies might find competitive advantage in being early adopters of AI. In the medium and long term, however, today’s cutting-edge technologies will become ubiquitous. The advantages of having access to data and algorithms will diminish.

So if the heart of competitive advantage is strategic differentiation, how then will companies achieve it? The answer may lie in taking a step back from the technology and considering another resource: people.

Algorithms excel at being hyperrational: extrapolating and drawing logical conclusions to maximize efficiency. People who are rational thinkers are easy to manage and fit well into organizations. But hyperrationality carries within it a profound problem when it comes to defining strategy. Firms that rely on the same or similar reasonable big-data analyses and algorithms as everyone else will struggle to differentiate themselves strategically.

Human beings, with highly developed soft skills, can consider the emotional context and connections of strategic decisions. They can be contrary and ask difficult, unexpected questions that result in actionable insights. They have imagination and can make intuitive leaps that AI is, at best, many decades away from replicating.

One of the key roles for human managers in helping companies differentiate themselves will be to go to the core of exploring what a company is — to consider its purpose and identity, to set its goals for the future. The human capacity for moral and spiritual discretion will be paramount to the sustainability of companies.

Good managers also have the ability to make tradeoffs. They reconcile different points of view within a company and manage complex and unaligned stakeholder demands. They balance the need to make short-term profits with the need to take risks for longer-term growth, despite the uncertain payoffs.

AI brings us to an inflection point in strategic decision-making for competitive advantage. Managing it successfully will depend on keeping a clear view of differentiation. We must harness the power of technological change without allowing ourselves to get swept away by its trends, precisely because everyone else is.

Strategy differentiation will depend on how firms combine technology with their internal organizational capabilities and their ability to be more human — and sometimes unreasonable, emotional, insightful and creative — and not more machine-like.

Managing talent with data and humanity

By Marta Elvira, Professor of Managing People in Organizations and Strategic Management, and holder of the Puig Chair of Global Leadership Development

Companies are increasingly using artificial intelligence to assist decision-making on HR strategies. AI tools open up new possibilities in understanding the strengths of a company’s workforce as well as tailoring its talent development practices to strategic goals.

This is not a peripheral issue. Better performing companies are those that foster the adaptation abilities of their workforce, developing and compensating professionals who contribute to innovation. Firms’ long-term sustainability greatly depends on their competence in managing their high potentials and encouraging creativity through diversity. This means making sure that human capital strategies are prioritized on top management teams’ and boards’ agendas.

AI can help us move past broad initiatives, so we can focus on individuals. The ability to analyze data and identify patterns will allow us to pinpoint with greater accuracy what each person is likely to be good at, based on current strengths.

AI can also help managers make informed decisions on training. As data sets grow, algorithms will be able to detect what’s working across organizations and suggest how to implement best practices in ways tailored to individual needs. For employees, this should result in greater job satisfaction, learning and productivity.

At the level of corporate governance, AI can help boards understand and offer better guidance on talent issues. For this to happen, board members must get informed about data and AI. And HR managers must get their data house in order. Most HR departments don’t gather nearly enough suitable information, and they frequently compound the problem with suboptimal database management. When companies do have databases that are large and well organized enough to deploy AI tools, they must then consider the objectives of those decisions. In recruitment, for example, if the focus is exclusively on reducing costs instead of identifying better hires, the long-term outcome could be worse for everyone.

It is also imperative that companies guard against the lure of what Wharton’s Peter Cappelli calls “cool tools.” Today’s recruitment and people-management software tools tend to be strong on engineering and weak on psychology. They have been developed by people who, in the main, lack significant real-world management experience. The claims developers make for them may not lead to better real-world results.

Fairness is another concern. Algorithms can be systematically biased, reflecting hiring managers’ biases regarding anything from gender to race to education. Biases risk being replicated at scale across a whole company.

Human oversight of AI decisions will increase in importance as the power and ubiquity of the technology grows, requiring a people-first approach from managers with emotional intelligence and integrity.

Thinking outside the black box

By Sandra Sieber, Professor and head of the Information Systems Department at IESE

The next major phase in the evolution of artificial intelligence has already begun. Managers need to be aware of what’s possible, not only now but also around the corner, and the implications it will have for how we work.

Today’s AI falls mainly into the category of so-called “narrow” AI, with enough computing power to deliver superhuman accuracy and speed when performing single tasks in single domains. Hence, despite its raw power, its applicability remains relatively limited. However, “broad” AI has the potential to be much more disruptive, once it is able to operate in a multi-task, multi-domain, multi-modal manner. In the near future, broad AI will impact risk modeling, prediction making and even strategic planning.

In this world where AI can make faster, better-informed decisions than humans, what will the role of managers be? The answer to that can be found in some of AI’s inherent limitations, which even broad AI is unlikely to overcome.

For all their power, algorithms don’t solve everything and will only ever be as good as the data fed into them. Self-reinforcing biases are a real risk, as was demonstrated by an MIT research project in 2018, which discovered that leading AI-powered face-recognition systems were “racist” — incorrectly determining the gender of dark-skinned females because the algorithms had been trained primarily with images of white males. Another system used by U.S. courts was found to be prone to misjudge the likely recidivism of black defendants because of biased data. Human managers will need to be trained to be on the alert for such potential biases in order to provide a safeguard against blind acceptance of AI-generated decisions.

This “decision curation” is especially important in the face of another AI characteristic — “black-box” decision-making. This is the idea that we can understand what goes into AI systems (data) and what comes out (useful information) but not what goes on inside. As AI becomes more sophisticated, the math it uses is becoming so complex that it is sometimes beyond human comprehension — even for the people who wrote the algorithms. As a result, we can’t “show the working” and explain how AI reaches its conclusions.

This has implications for transparency and accountability when the system’s output is used to make important — perhaps even life or death — decisions. Managers, therefore, must understand the context in which black-box AI decisions are to be implemented, and consider their consequences. To do this requires a (thus far) uniquely human quality: imagination. Companies often pay lip service to the idea of thinking outside the box; in the future, this will be a literal necessity. The ability to ask “what if?” — to look before leaping — is paramount to effectively and ethically harness the power of AI.

Data readiness starts at the top

By Anneloes Raes, Professor of Managing People in Organizations at IESE

Artificial intelligence promises to be a powerful driver of change in ways we cannot yet forecast. Even so, it’s worth considering how management should prepare their companies for some of the changes that we can already see.

Data will be the most important commodity of the future. As such, a top-to-bottom company culture of readiness — in terms of data governance, architecture, traceability, accessibility and visualization — will be a prerequisite to survive and thrive in an AI world.

In my research on top management teams, I have found that the ones that operate at peak performance are those that exhibit high cognitive flexibility — meaning they are open to new ideas, take a lot of different perspectives into account, and are able to change their opinions in light of incoming information. Cognitive flexibility increases the creativity with which information is interpreted and alternatives are generated.

Top management teams may not need coding skills or deep technical knowledge of AI, but they do need a robust understanding of its possibilities in order to ask the right questions and consider all the angles, without prejudice or fear. Shaping an organizational culture that encourages this open, agile, multidisciplinary culture is crucial.

Usually, any cultural change should start by educating those at the top. Again, my research has shown that what goes on in the C-suite has an influential effect on the rest of the organization. So, the more the top management team is able to model the behavior it seeks, the more middle managers and other employees will start to align their own behavior and get excited about the possibilities of AI. In an attempt to be the change they seek, many leading companies are actively recruiting MBAs who are further along the AI learning curve than senior management, so their knowledge and enthusiasm can permeate the entire organization.

AI will increasingly automate business processes, which implies fewer people will be involved in operations. At the same time, AI will increasingly free talent from the constraints of location. Management structures will become much more fluid. Managers from anywhere in the world can use AI to make better-informed decisions.

Advances in automatic translation and virtual assistants will allow the brightest talent to manage more easily and effectively in international and multicultural settings, even if working remotely. AI will help geographically dispersed managers get the best from individual team members, wherever they are. Multidisciplinary teams in diverse locations will be linked by AI-derived best practices, tailored to their own needs. The more participative, integrative and cooperative the leadership is, the more motivational it is for employees. For all AI’s disruptive effects, it’s worth sticking to the foundations upon which successful organizational cultures are built.

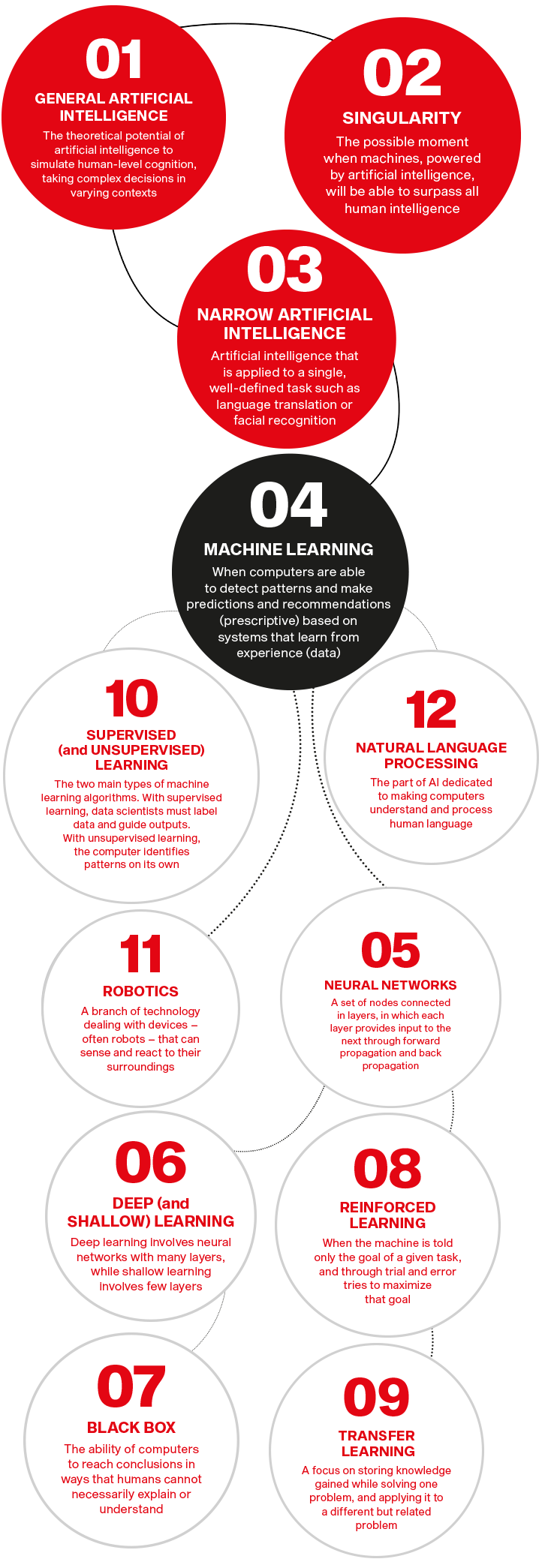

12 key words

02Artificial intelligence, real leadership

A primer of key AI concepts from Javier Zamora of IESE’s Information Systems Department

Dario Gil: “It is imperative for leaders to separate AI reality from hype”

03Artificial intelligence, real leadership

Dario Gil is Chief Operating Officer of IBM Research and vice president of AI and quantum computing at the technology giant.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is evolving faster by the day and its application impacts almost every industry. But it also affects the way corporations work. IBM’s Dario Gil knows firsthand how this technology is creating new challenges for leadership and management. Here, Gil talks about the present and future of AI as well as his vision of quantum computing.

What do you mean when you say that AI is the new IT?

As happened with IT, many companies are viewing the creation and adoption of AI as an essential part of their success. There are parallels in today’s efforts with the previous IT experiences: corporations are creating internal AI departments and aggressively recruiting AI experts, trying to determine how this technology might be used. Furthermore, the hype around AI is increasing every day. The term has become a buzzword which is replacing other tech terms such as IT, automation and data analysis; many times, in ways that aren’t really about AI.

There are usually two visions of AI: a utopia of machines improving our world and a dystopia where humans are superfluous. Which is the real one?

I would say that neither of these is the reality of AI. We have seen its rise being accompanied by both these perspectives: boundless enthusiasm for its ability to transform our lives, and fear that it could potentially harm and displace us. At IBM, we are guided by the use of artificial intelligence to augment human work and decision-making. Our aim is to build practical AI applications that assist people with well-defined tasks. There’s no question that the arrival of artificial intelligence will impact certain jobs, but we believe people working collaboratively with AI systems is the future of expertise.

Then how will AI change employment?

History suggests that, even in the face of technological transformation, employment continues to grow. It is the tasks that are automated and reorganized where the transformation occurs, and workers will need new skills for these transformed tasks. Some new jobs will emerge: “trainers” will be required to teach AI systems how to perform, and another category of “explainers” will be needed to help convey how these intelligent devices have arrived at a decision. In some areas, a shortage of qualified professionals may exist and the emergence of AI systems further highlights the need for individuals such as cybersecurity professionals.

Do we need to understand algorithms to be able to work with them?

I don’t believe that it is mandatory for every AI system to be understandable at a very precise level, but I expect us to reach a foundation of trust through our testing methodologies and experiences. In some cases, users of AI systems, such as doctors and clinicians, will need to justify recommendations produced by one of these systems.

How can business leaders adapt to the new AI landscape?

It is imperative for CEOs, senior leaders and managers to become knowledgeable about AI, to separate reality from hype and to start developing a strategy on how they might use AI systems within their business. The nature of leadership will likely change in many aspects of the “hard” elements, such as data-driven decision-making, and leaders will need to embrace “softer” aspects of leadership, such as helping their employees work together. They will also have to identify ways to enable the partnership between their workers and the AI systems.

“Business leaders and managers must take the first steps in being informed about AI and quantum computing”

What organizational challenges will companies face?

One major challenge is determining whether their company will drive the AI strategy and capabilities internally, or whether they will work with external organizations to get support. Many considerations impact this decision, including the ability of the company to attract, develop and retain key AI talent. I also believe that it is critical for companies to have a senior leader focused on AI strategy and execution for their business. It could be achieved through the creation of a new role such as the chief AI officer, but it could also become part of the responsibilities of existing leaders, like the chief technology officer or the chief data officer.

How do you envision the impact of quantum technologies?

IBM is focused on advancing quantum information science and looking for practical applications for quantum computing. In September 2017, our team pioneered a new approach to simulate chemistry on our quantum computers. Now, we expect the first promising applications: the discovery of new algorithms that can run on quantum computers and untangle the complexity of molecular and chemical interactions, tackle complex optimization problems and address artificial intelligence challenges. These advances could open the door to new scientific achievements in areas such as material design, drug discovery, portfolio optimization, scenario analysis, logistics and machine learning.

What other steps have to be taken in the coming years regarding AI and quantum technologies?

Business leaders and managers must take the first steps in being informed about AI, quantum computing and the potential impacts and benefits to their companies. We have to move from a narrow to a broader form of artificial intelligence that enables the application of AI systems from one task to another. Leaders must begin to define a strategy for the development and use of it for their specific business, and then their style of leadership will evolve to embrace the value that this brings in decision-making. For quantum computing, we encourage organizational leaders to become “quantum ready”: to get educated on quantum computing, identify applicable use cases and explore the development of algorithms that may lead to demonstrations of quantum advantage.

Creating the quantum computers of tomorrow: an IBM cryostat wired for a 50 qubit system. Credit: IBM

Thomas W. Malone: “A lot of people are more worried than they need to be about computers taking away jobs”

04Artificial intelligence, real leadership

Thomas W. Malone is Professor of Management at MIT Sloan School of Management and founding director of the MIT Center for Collective Intelligence.

If artificial intelligence awakens fears of a dystopian workplace where machines replace humans and humans exist in lonely isolation, MIT’s Thomas W. Malone imagines just the opposite. He sees a future in which groups of people, aided by technology and connected as never before, are able to take smarter decisions. His new book, Superminds: The Surprising Power of People and Computers Thinking Together, looks at these human-computer collaborations.

What is a supermind?

I define superminds as groups of people, and often computers, working together in ways that at least sometimes seem intelligent. These superminds are around us all the time and come in many different shapes and sizes, all the way from hierarchical organizations to local town hall democracies, from global markets to scientific communities and local neighborhoods — and many, many other kinds of groups.

These superminds run our world. It’s these groups of people, not individuals, that are responsible for almost everything that humans have ever accomplished.

If humans have always worked in groups, what’s new?

What’s new is that we have a new communication technology that’s far more powerful than any communication technology that we have had before. This new computer technology helps us do two kinds of things. The first is perhaps the newest, which is that computers can sometimes do intelligent thinking themselves. They can use their specialized kinds of artificial intelligence — because no computer today is anywhere close to having the general intelligence that any normal human has — to help do some of the actual thinking that needs to be done to solve whatever problems these human groups are trying to solve. These computers can also provide what I call hyper-connectivity: connecting people to other people and also to computers, at a scale and in rich new ways that were never possible before.

How do we know group decisions are better decisions?

I don’t think there’s any guarantee that they’ll always be better, but I think in general the odds improve. It of course depends on the kind of decision. But there are a number of potential benefits you get from larger groups. One is just brute force. Many kinds of work, including many kinds of intellectual work, require just a lot of thinking, a lot of possibilities that need to be tried, and if you can try 10,000 rather than 10 of them you’re more likely to find one that works better. Another thing that larger groups do better than smaller ones is that they can more easily have more diverse points of view. They look at the problem from more perspectives and are more likely to see different opportunities for how to evaluate things or more things to try. With large groups you also have more possibilities of finding people with very unusual capabilities.

“It’s easy to imagine machines that are as smart as people. It’s a lot harder to build such machines”

With AI, will computers do more of the thinking?

We have to realize the difference between two kinds of intelligence. The first is specialized intelligence: the ability to achieve specific goals in specific environments. The second is general intelligence: the ability to achieve a wide range of different goals in different environments. Even the most advanced artificial intelligence systems in the world today are only capable of specialized intelligence. Any normal human five-year-old kid has far more general intelligence than the most advanced artificial intelligence program in the world today.

Until we have computers that are as good as people at everything people can do, humans have to be involved in every use of computers. They have to decide which programs to run with. They have to decide what to do when things go wrong. And often they’ll be doing the parts of the problems that the machine couldn’t even do at the beginning.

Are computers with general intelligence close at hand?

People have been asking questions like this ever since the beginning of the field of artificial intelligence in the 1950s. And for the last 60 years, the answer has been about 20 years in the future. Is it theoretically possible that this time they’ll be right? Yes, it’s theoretically possible. But I think we should be very skeptical of anyone who confidently predicts that we’ll have human-level artificial intelligence any time in the next few decades. It’s easy to overestimate the potential of artificial intelligence because it’s easy to imagine machines that are as smart as people. It’s a lot harder to build such machines than imagine them.

What does this mean for the future of work?

I think that a lot of people are more worried than they need to be about the problem of computers taking away jobs. Automating jobs will probably take longer than people expect. People also forget about delays in implementation. Even if we had today a perfect human-level general AI computer in the lab at MIT, how soon do you think that would take over all the jobs in the world? Tomorrow? Next week? Next year? No, it would take decades, even if we had the complete technology today.

One of the interesting things about markets, as superminds, is that they’re very resourceful, very creative at figuring out new ways of employing resources. It’s very easy for us to imagine the jobs we know disappearing, and much harder for us to imagine the jobs that don’t even exist yet. But just because it’s hard to imagine them, doesn’t mean they won’t exist.

How companies are adopting AI

05Artificial intelligence, real leadership

6 characteristics of early AI adopters

1 Larger businesses

2 Digitally mature

3 C-level support for AI

4 Focus on growth over savings

5 Adopt AI in core activities

6 Adopt multiple technologies

4 areas across the value chain where AI can create value

Produce Optimized production and maintenance

Promote Targeted sales and marketing

Provide Enhanced user experience

Project Smarter R&D and forecasting

5 elements of successful AI transformation

1 Use cases/sources of value

2 Data ecosystems

3 Open culture and organization

4 Workflow integration

5 Techniques and tools

Download How companies are adopting AI

Why management matters

06Artificial intelligence, real leadership

By Jordi Canals

The possibilities of artificial intelligence in managerial decision-making are not only growing, but are also encompassing a wider scope of activities and business functions in organizations.

CEOs and senior executives have a responsibility to become familiar with these tools and their application. Knowing AI’s weaknesses, as well as its strengths, is indispensable for senior managers. But the real challenge that AI poses is this: Will management remain relevant in an AI world?

In answering this question, we need to consider that while there is little doubt that AI can aid in decision-making, management is not only about making decisions. Management is about defining and setting a sense of direction for the company and some coherent goals. It involves designing policies and executing actions in a consistent way. It aims at engaging and developing people. It needs to serve a wide variety of stakeholders. It should balance different requirements and constraints, in the short and the long term. Management is not only about some specialized knowledge. It is also about good judgments, initiative, creativity, humility to learn and positive impact — qualities that AI can complement, but cannot replace.

“It is impossible to create something new and relevant without the human passion for discovery and innovation”

The long-term success of most companies depends on developing good management teams that can harness technology innovation and apply it well. Management involves making prudent judgments. Machines that learn are not designed to make judgments about good and evil. Humans can train them by feeding data of what is good or bad in specific cases, but machines cannot go from specific data to making a general ethical judgment. The use of prudence and good judgment in AI is indispensable; both validate the quality of data and the processes by which algorithms make recommendations or decisions. The failures associated with AI tools due to fake data or incomplete algorithms are already numerous. AI can complement management when data are reliable and algorithms are well designed.

Good managers assume responsibility for their actions and omissions. In situations where complex human behavior and human interaction are critical, we need good human judgment and people who always assume responsibility when making decisions. The legal consequences of AI are enormous for individuals and companies, in particular those related to the legal responsibilities of machines that make decisions.

No matter how transformational AI may be for companies, CEOs and senior executives still have some very fundamental roles, responsibilities and challenges that only competent leaders can address. Good managers do so with a combination of rational judgment, emotional intelligence, ethical principles, freedom and entrepreneurial initiative to make decisions with a holistic perspective.

Purpose. The first challenge is to offer a good answer to the question: “Why does my company exist?” Any company needs to be explicit about its purpose. Shareholder returns are indispensable, but not a sufficient condition for a company to exist in the long term. Companies need to nurture and grow their reputation with small and big steps, customers need to feel a connection with the company and professionals should also be attracted to it. The firm’s purpose is indispensable.

Uniqueness. A second challenge is how the CEO and executive committee consider that their company is unique for customers and professionals. They should take key decisions that will make the company different from competitors. This involves not only thinking about investments and other commitments to create some competitive advantages, but also exploring how to shape the soul of the firm: the values that inspire their actions and the activities at which the firm is really special in the eyes of customers and employees. The firm’s value proposition should be clear to the customer, easy to understand and consistent with the firm’s policies.

Sustainable economic value. A third challenge that management should tackle is to make sure that the company is not only unique and special to customers, but also that it creates economic value in a sustainable way for all stakeholders, including shareholders.

Creating the future. Respected senior managers think about the future, undertake new business projects and help create the future with energy and passion. They are keen to develop new ideas with an entrepreneurial mindset. There is something truly human in the process of creating new products, services or companies that can make a positive difference. It is impossible to create something new and relevant without the human passion for discovery and innovation and desire to have a differential impact.

Broader impact. Finally, companies need to think not only in terms of how much value they create, and which purpose they have, but also about the wider impact that they have on society. This approach involves much more than managing different stakeholders. Companies need to be responsible citizens in the society in which they live and operate.

Senior managers are dealing with fascinating changes in the business world and society, with technology and data being used in much smarter ways. At the same time, we need to ask ourselves those fundamental leadership questions. AI does not know how to frame them, or to provide answers to them. Good senior managers do. Our challenge is how we use AI tools to make our companies not only more competitive, but also more human. In this new AI world, management has a role that is more relevant than ever.

Jordi Canals is Professor of Strategic Management at IESE and was the school’s dean from 2001 to 2016. He co-organized The Future of Management in an Artificial Intelligence-Based World conference in April 2018 with the current dean, Franz Heukamp. They subsequently co-edited a book of the same name, based on the conference.