New paradigms in purpose, ownership and engagement

01New paradigms in purpose, ownership and engagement

A character-building issue

They say crisis reveals character, and the coronavirus crisis has certainly revealed what we’re made of. As country after country adopted emergency measures, businesses began to show their true colors. Some rose to the occasion. Yet, we can also find media stories of businesses that have not reacted so well. While every company has been forced to do some form of damage control, some of the damage has been of their own making. As one headline reminds us: “How companies behave amid coronavirus will determine their fate later.”

In one of the live sessions that we began offering on LinkedIn, a participant asked: “Is redundancy compatible with having shareholders and investment funds that only expect short-term profits and returns?” To which my colleague Miguel A. Ariño responded with an emphatic “No.” While sensitivities are changing in this regard, he admitted that this mindset still hadn’t filtered through to many directors.

The crisis has forced the world to stop and think. “The last global crisis didn’t change the world. But this one could,” wrote one business commentator. With a global recession quite certain, the stakes are literally life or death as we decide the path forward. If not “a crisis of capitalism,” the commentator continued, “it might better be understood as the sort of world-making event that allows for new economic and intellectual beginnings.”

That’s what this issue of IESE Business School Insight provides: food for thought on where the governance models that have guided our companies may need to go next. Our report, completed just as the coronavirus was declared a pandemic, continues an important conversation that for IESE began long ago; that was given fresh impetus by the U.S. Business Roundtable and Davos manifestos; and that now seems of utmost urgency as we adjust our businesses and societies to the new normal.

Many of us have more time than usual to read and reflect. So, as you read this report, reflect on the timeless lessons for leadership contained therein that can serve you as you write your own story going forward. Above all, use this crisis to show your true character.

New paradigms in purpose, ownership and engagement

A conversation around the purpose of business was already underway when the coronavirus hit. For many, this global crisis marks a before and an after. What are the issues that executives and directors need to reflect on now, as they look for purpose beyond profits in a radically altered business environment?

“What kind of capitalism do we want?” That was the question that Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum, posed on the occasion of WEF’s 50th anniversary, adding that it “may be the defining question of our era.” The theme of the WEF Annual Meeting held earlier this year in Davos – “Stakeholders for a Cohesive and Sustainable World” – hinted at the answer, which was spelled out in a new Davos Manifesto that called for stakeholder capitalism to become the new dominant model for doing business in the 21st century.

“The debate regarding the role of stakeholders within a firm is, primarily, a governance debate,” notes IESE’s Mireia Giné, who participated in the Davos summit. “And as with most challenges that require robust leadership to change the way we live, work and interact, transformation starts from the top. Corporate governance sits at the heart of this.”

Corporate governance encompasses all the rules, practices, processes, systems and values used to direct and manage a company, with the board of directors being one of the key mechanisms in ensuring the company fulfills its fiduciary responsibilities. Lately those responsibilities have grown significantly more complex – and more important than ever for a company’s long-term success.

“Shifting customer demands and social expectations, particularly in relation to climate and gender equality issues, are driving boards to make sure the goals of a company’s executive team are aligned with those of owners and other stakeholders,” says Giné.

Mireia Giné believes the debate regarding the role of stakeholders within a firm is a governance debate.

Whether it’s “the end of an era for corporations” or “a watershed year in the evolution of corporate governance” as pundits predicted at Davos, one thing is certain: “As leaders, we must take the opportunity to evaluate whether our businesses are truly serving society in the best possible way,” says Giné. “We have a unique chance to give meaning to stakeholder capitalism by engaging in a governance debate and devising new structures to implement it across our organizations.”

Here, we highlight the high-level issues that need to be considered by the highest level decision-making body of your company, for the sake of fostering sustainable, long-term economic growth in the interest of your various stakeholders.

Repurposing capitalism

The move toward stakeholder capitalism has been a long time coming. The Milton Friedman-style shareholder primacy dogma that dominated Western corporate governance throughout the latter part of 20th century is showing its age. We have talked about “private ownership” and “the owners of the company” as if we were talking about owning a washing machine, remarks Colin Mayer of Oxford Saïd Business School. In so doing, we’ve reduced the concept of a firm to little more than a nexus of contracts, held together by the board, whose job has been to do the bidding of those who provide the capital.

But a company, Mayer stresses, is much more than a machine. It’s a complex organism: it depends on and impacts human, social and natural assets, from employees to the environment. To govern it otherwise will lead to failure. The corporate scandals – and the resultant political instability we’re experiencing around the world – are evidence that a more enlightened view is needed, one that “promotes welfare, not just wealth.” And if we don’t seize the moment, then it’s going to be seized by someone else, he warned, namely government regulators who may impose unwelcome restrictions.

As leaders, we must evaluate whether our businesses are truly serving society in the best way

Mayer proposes an enlarged concept of “owners” as “beneficiaries.” The directors manage the company in the interests of its many beneficiaries, acting more as trustees or stewards than as agents for shareholders. “Ownership is no longer just a set of rights; it is also a bundle of responsibilities. Corporations are no longer nexuses of contracts but nexuses of trust among stakeholders, overseen by boards of directors.”

Though making money is still important, “profit is not the defining purpose but rather a derivative of the primary purpose,” which Mayer describes as “to provide profitable solutions to the problems of people or the planet – and not create problems for people or the planet.” By proving themselves “trustworthy of being trustees of their many stakeholders,” companies will find themselves with more loyal customers, more engaged employees, more supportive suppliers – and happier shareholders. Recent studies bear this out.

While there is gathering momentum for this vision, the question before boards is: Is it their job to do this? With the exception of family firms, where it’s easier for a single founder-owner to set the purpose and require the management to execute it, the practical reality of corporate boards taking into account the competing interests of their many different stakeholders may lead to a situation of “accountability to everybody means accountability to nobody.”

6 keys for excellent directors

1. Act with responsibility and transparency

Act in the interest of your stakeholders, not just your shareholders. Think beyond compliance to living up to your responsibilities.

2. Strike the right balance

Support senior management while also supervising and controlling what they do. Be prepared to sacrifice some short-term results to benefit the company in the long term.

3. Avoid excesses

Don’t let special interests distract attention from accounts and financial statements.

4. Embrace talent and diversity

Diversity of gender, background and experience is essential for creativity, innovation and disruptive strategies, so don’t end up with a board of clones. Make attracting and retaining top talent a strategic priority.

5. Deal with digital transformation

Recruit talent with knowledge of data science and machine learning, and continuously train people in new technologies. Keep the company structure flexible and dynamic to react faster to change.

6. Avoid rookie errors

Designing a strategic plan in which the board doesn’t play a key role, and not following up on its implementation: don’t make these costly mistakes.

Source: Directors Forum, held annually at IESE Madrid.

To this argument, Mayer counters that accountability to a single person – i.e., the shareholder – means nobody else counts. In corporations where the ownership is highly dispersed among many different investors, Mayer believes it ultimately should fall to the board to set the purpose and execute it, ensuring a system of measurement to ascertain whether corporations are delivering on their purpose.

Furthermore, the law should impose duties on shareholders, he adds. Corporate law in the U.S. and U.K. currently constrains the potential of corporations to pursue a plurality of corporate purposes. That needs to change, he insists. And the tide appears to be flowing in his preferred direction.

Different paths to purpose

Are there examples of this purpose-driven, stakeholder-centric model of corporate governance in action? Yes, and Europe is home to many of them, including many family businesses.

Are there examples of this purpose-driven, stakeholder-centric model of governance in action?

Germany is well-known for its two-tiered model of a management board and an independent supervisory board split between elected employee representatives and shareholder representatives. This forces consensus-building and co-determination by design. U.S. presidential hopeful Elizabeth Warren drew inspiration from it in formulating her Accountable Capitalism Act, which would, among other proposals, require 40% of board seats of U.S. corporations to be occupied by workers’ representatives to help rebalance the boardroom. The idea of more worker representation on boards seems to enjoy broad public support.

Spain’s La Caixa Group represents another model – a private foundation that also counts corporate interests such as CaixaBank (a 40% holding). Jordi Gual, chairman of CaixaBank and an economics professor at IESE, says the reference shareholder provides stability and the long-term orientation that any business needs, allowing them to take a more stakeholder-oriented approach overall. The dividends generated by the holding company finance the foundation, which has an explicit social mission to promote education, research, culture and welfare for a wide variety of beneficiaries.

In the United States, such models are more the exception than the rule – though that is changing. Until 2010, directors of for-profit companies were not legally permitted to act outside the narrow stricture of shareholder-first. Since the creation of a new legal entity known as the Public Benefit Corporation, a growing number of U.S. for-profit companies are now incorporating as a PBC, officially embedding governing for the public good as part of their charter.

New ownership landscape

At the same time as executives and directors are grappling with changing expectations of corporations, they must also deal with a changing ownership environment. Ownership of public companies by a physical individual shareholder is dwindling, being overwhelmingly replaced by large institutional investors. Moreover, among those institutional investors, traditional ones such as pension funds, which typically have longer-term investment horizons, are also decreasing, being replaced by new types – hedge funds, private equity funds, sovereign wealth funds and exchange traded funds – with very different purposes, investment strategies and time horizons.

On top of this, more and more institutional investors outsource the management of their assets to professional asset managers. Some of these assets are actively managed, meaning a portfolio manager or team of managers is making buy/sell investment decisions on behalf of their client in an attempt to outperform the market. The big shift of recent years has been to passively managed index funds, where the portfolio tracks a market index or benchmark to generate consistent returns. The management fees associated with these kinds of funds are lower and they can perform better than actively managed funds, making them a relatively safe investment vehicle – thus, their popularity.

The proliferation of passive investing has attracted criticism for its outsized influence on the corporate governance of public companies. Jill Fisch of Wharton summarizes the main charges leveled against passive asset managers: they don’t engage with or challenge companies enough, nor do they have the incentive or resources to do so because they compete on costs; worse for the proponents of stakeholder capitalism is that they don’t act in the interests of society.

Fisch, however, takes issue with these criticisms. If we take the enlightened sole owner as the benchmark for engagement decisions, then of course there will be costs. But that’s what she calls “the Nirvana fallacy,” comparing passive investors to an ideal world of fully informed, perfectly engaged investors that doesn’t exist. In her view, the so-called Big Three of BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street do use the significant clout of the passive assets under their management to engage with companies on purpose and values as factors in their performance. Size creates more leverage in their engagements. And as asset managers offer more socially responsible funds that exclude entire industries, such as arms or tobacco, or promote Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) concerns, they have the ability to wield their power on an industry-wide scale for good. (See the interview with BlackRock’s Amra Balic for more on this.)

Indeed, according to research by IESE’s José Azar, Miguel Duro, Igor Kadach and Gaizka Ormazabal, pressure from the Big Three about the risks that climate change creates for investors is having a positive effect on corporate governance activities, contributing to their portfolio companies reducing their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. “Our analysis indicates that an increase in ownership by the Big Three is associated with a statistically and economically significant reduction in emissions,” they assert.

“This may seem puzzling,” they admit, “given that the Big Three have been criticized for tending to vote against climate-related shareholder proposals.” To explain this apparent contradiction, the authors state that the Big Three’s preferred method of constructive conversations with management, rather than protest voting, seems to be generally more effective at getting companies to take stakeholder concerns seriously. And given that emissions and climate change are global issues that transcend any one company’s or nation’s ability to solve singlehandedly, the Big Three, with their boundary-spanning portfolios, are uniquely placed to exert positive pressure for socially responsible corporate governance on a global scale.

Miguel Antón found a link between common ownership and excessive CEO pay.

José Azar has been pursuing new lines of research into the phenomenon of common ownership.

Common ownership

That said, the fact that the Big Three hold about 80% of all indexed money in the world is not entirely great news for corporate governance, especially when they constitute the largest shareholder of roughly 1 in 5 publicly listed corporations and close to 90% of S&P500 firms, often including the largest competitors within the same industry. Bloomberg Businessweek called indexing “one of the biggest shifts in corporate power in a generation.”

Several IESE professors are pursuing new lines of research into this phenomenon known as common ownership. IESE’s Miguel Antón and Mireia Giné, for instance, have found a link between an increasing amount of common ownership in U.S. public companies and excessive CEO pay. In 2016, the median annual compensation for CEOs of S&P 500 companies was around $11 million. At the same time, a majority of individual investors wanted to see more pressure put on public companies to rein in executive pay. In the United States, CEO pay has grown almost 1,000% since 1978. This has opened up massive inequality between very high earners and the bottom 90% of ordinary workers – a situation that many consider intolerable, feeding the rise of the populist backlashes we’re witnessing around the world. In spite of this, according to 2016 data, asset managers voted to approve executive compensation packages about 96% of the time. Analyzing data over the past two decades, Antón and Giné found strong empirical evidence that “executives are given weaker incentives to compete aggressively when their industry is more commonly owned” and that “high levels of common ownership rationalize performance-insensitive pay.” In other words, among industry rivals held in the same portfolio, CEOs can still get paid top dollar for not engaging in strategies such as price wars – something that in banking, for example, tends to benefit customers looking for lower fees – because doing so could negatively impact their competitors’ share price and dampen total portfolio returns.

Antón and Giné build on work by José Azar, who previously studied this effect among U.S. airlines. The Big Three own up to 20% of each major U.S. carrier. Analyzing industry data between 2001 and 2013, Azar et al. found that the more common ownership of certain airline stocks there was, the less market competition there was between them and the higher the ticket prices, by as much as 12% on certain routes. This is not to say there’s collusion on the part of common owners. Rather, it’s that portfolio managers seem to lack the impetus to push company management to engage in more competitive practices such as price wars, investing in R&D, improving operations, and so on. Everyone takes the path of least resistance: managers are incentivized to maximize the value for all firms and relax the competition between them. Common owners are rewarded with higher stock prices – though consumers ultimately pay a price in the form of more expensive airline tickets, even as passenger numbers dwindle.

Azar is extending his research with IESE’s Xavier Vives. They recently modeled sectors of the U.S. economy and found that higher effective market concentration, including in the form of common ownership, can also lead to lower equilibrium wages, lower output, lower labor share and lower capital share. Yet Vives remains cautious about calling for regulatory intervention and antitrust enforcement regarding common ownership. He agrees that more focus and scrutiny are needed, but urges more research. While there’s evidence of common ownership reducing competitive pressure, there’s also evidence of it contributing to more efficient governance – such as improving information-sharing between firms and helping them internalize spillovers where R&D investments are complementary. The context matters, too: intra-industry common ownership could have an anti-competitive effect, while inter-industry effects could be pro-competitive.

Xavier Vives prefers more research to regulatory intervention regarding common ownership.

For their part, asset managers disagree as to whether there is a real problem, but they’re closely watching how all these debates play out, given the potential ramifications for their business models. What’s in no doubt is that patterns of ownership have changed, says Vives, rendering the old maxim of “own-profit maximization” a moot point. At the very least, we can expect to see greater emphases on transparency and disclosure of engagement priorities and voting records, and added pressure to introduce new voices and inputs into boardroom discussions.

Activists on the board

Aside from index funds is another investment vehicle that’s impacting the way companies are governed: hedge funds. Unlike index funds, hedge funds attract a more activist breed of investor: high-net-worth individuals with more aggressive investment goals, usually looking to maximize profits in the shortest amount of time. As major shareholders, they can shake up corporate governance, agitating for a radical restructuring or for selling off part or all of the business, which may deliver them quick returns but may also lead to layoffs and may not be in the best long-term interests of other stakeholders. By the time the value destruction comes to light, these slash-and-burn investors have long since cashed out.

Columbia Law School’s John C. Coffee, Jr., notes the difference between having an activist hedge-fund employee on a board versus other types of directors, even if they may be activists themselves. In general, he finds that “firms appointing an activist experience an increase in information leakage of 25-27 percentage points.” Significantly, that leakage is “driven by the appointment of activist hedge-fund employees to the corporate board, and not by the appointment of other persons, such as industry professionals.” Moreover, “bid-ask spreads increase by statistically meaningful amounts,” particularly “in those cases in which a hedge-fund employee is appointed to the board.” Tellingly, the market response is much more positive when the slate of fund-nominated directors aren’t employees of hedge funds, he adds.

“Hedge-fund activism seems closely aligned with informed trading,” says Coffee. “That’s not necessarily the same as illegal insider trading. We don’t know who the beneficiaries are. But it is certainly asymmetric. And it is most likely harmful to shareholders.” He suggests these activist directors “tip information to their allies to assemble a ‘wolf pack’ to be able to put more pressure on management.”

Although critics of hedge funds regard them as “the epitome of all that’s wrong with capitalism,” London Business School’s Alex Edmans doesn’t see their disruptive presence as categorically a bad thing. He cites instances where hedge-fund activists can make improvements, similar to a consultant or turnaround specialist hired for a few months. “Their shorter holding periods give them a sense of urgency, and the option to exit gives them teeth that can overcome managerial entrenchment. They can force the firm to refocus on its core expertise, redeploy human capital and change board-level expertise, leading to a more efficient allocation of resources that results in increased innovation output in the long term, measured by both patent counts and citations.” The key is for management to turn activist initiatives into business improvements that have a positive impact going forward.

Resisting short-termism

Whichever side of the debate you come down on, one message is consistent: short-termism poses a threat to long-term economic prosperity. We’ve reached “a tipping point,” says corporate governance expert Martin Lipton, “and decisive action is imperative” to “recalibrate” and “reconceive of corporate governance as a collaboration among corporations, shareholders and other stakeholders working together to achieve long-term value and resist short-termism.”

Creating better boards

The complexity of today’s consumers. Digital disruption. Geopolitical risks. To this list of corporate governance challenges add one more: the problem of short-termism, which the 2008 global economic crisis laid bare. Over the past decade, a new corporate governance framework, predicated on sustainable long-term value creation, has emerged as the new way forward.

To deal with these challenges, bigger, more sophisticated boards are needed, says Martin Lipton. Boards need to be diverse, in terms of ethnicity and gender. And the typical eight directors could be expanded to 12 or 15, serving for five or six years max. We need board members knowledgeable in the strategies, methods and business models of the Googles, Apples and Microsofts of the world. Take Facebook: “No one asked the right questions as to the societal impact of its activities. It was enormously profitable, but there was nobody on the board asking, ‘What’s the impact of doing this?’”

Regarding activists, Lipton says, “You don’t always have to fight tooth and nail to defeat them.” Sometimes the best approach is to work something out. That’s why it’s so important to have collegial directors: “A director’s personality, leadership and communication style will affect overall board dynamics. Remember, a board functions best when it works in unison with the CEO and management team. Maintaining that collegiality is key.”

Other important criteria for directors are competence, character, professionalism, sound judgment and, above all, integrity. “Even if you have smart people, if they don’t have the right moral compass, it’ll lead to failure.”

Jordi Canals interviewed Martin Lipton, founding partner of the law firm Wachtell Lipton Rosen & Katz, about his WEF-sponsored publication, “The New Paradigm: A Roadmap for an Implicit Corporate Governance Partnership Between Corporations and Investors to Achieve Sustainable Long-Term Investment and Growth.”

We’ve reached a tipping point. We must reconceive corporate governance as a collaboration among stakeholders

This echoes central tenets of the 2020 Davos Manifesto: A company treats its people with dignity and respect; it serves society at large through its activities; and it responsibly manages not just near-term but also medium- and long-term value creation “in pursuit of sustainable shareholder returns that do not sacrifice the future for the present.”

The clarion call that Jordi Canals, head of IESE’s Center for Corporate Governance (CCG), issued a decade ago in his book, Building Respected Companies, has never been more relevant: “As one of the central institutions in modern society, the firm is not just an engine of wealth creation and jobs, but an agent of change, a driver of innovation and people development. Boards should realize how critical their role is for the companies they lead and the well-being of societies at large. Beyond overseeing financial and nonfinancial performance indicators, the board has a moral obligation to support the long-term success of the whole firm – and not only for certain shareholders. Those who aren’t committed to this vision of the firm should ideally not be given a place on the board of directors. Its long-term success requires good governance.” How’s yours?

More info: This article was informed by an executive summary by Tom Vos (KU Leuven), with additional reporting by Steve Tallantyre, of the conference “Corporate Governance and Ownership with Diverse Shareholders,” held at IESE Barcelona. The conference was organized by IESE’s Center for Corporate Governance (CCG) and the European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI), with support from the Social Trends Institute. To find out more, go to ecgi.global/news/event-report-ownership-diverse-shareholders.

Watch: Corporate governance and ownership with diverse shareholders

Amra Balic: “Value is extending to values”

02New paradigms in purpose, ownership and engagement

Amra Balic is head of BlackRock’s EMEA Investment Stewardship team based in London, responsible for company engagement, public corporate governance, stewardship and responsible investment across Europe, Middle East and Africa on behalf of BlackRock’s clients globally.

Every year, BlackRock Chairman and CEO Larry Fink’s letter to CEOs makes headlines, and 2020’s was no exception. This time he put the climate front and center, announcing that sustainability would be “integral to portfolio construction and risk management.” BlackRock would be exiting certain investments such as thermal coal and, as the world’s largest asset manager, it would bring its weight to bear on the companies whose shareholders it represented: “We will be increasingly disposed to vote against management and board directors when companies are not making sufficient progress on sustainability-related disclosures and the business practices and plans underlying them.”

Fink’s previous letters have been no less newsworthy. He made “the inextricable link” between purpose and profit, and urged companies to prioritize value for stakeholders and positive social impact, long before the U.S. Business Roundtable issued its own similar statement in August 2019.

For Amra Balic, these are all positive signals that mark a shift in investment priorities. In her role, she meets the boards and management teams of the companies her clients are invested in, representing their concerns and encouraging those companies to adopt business practices consistent with their long-term interests. Here she explains why this role is so important and why, despite the challenges, she remains optimistic.

How have you seen the conversation changing?

Just a few years ago, the most important element in our ability to manage money was around value, but today it is about both value and values. This comes up in many of our conversations with asset owners. Some have very strong views on the (often ethical) values they want to capture in their investments. Others focus on maximizing shareholder value. We don’t impose our views. Our job is to help them achieve their objective, whether driven purely by value or by both value and their specific values.

How does Investment Stewardship work?

To inform our voting and to promote sound corporate governance consistent with sustainable, long-term value creation, we engage with company leaders on key topics that could have material economic, operational or reputational ramifications for the business. We do this to give companies feedback, as a long-term investor, and for us to understand their approach. Where and when appropriate, we hold directors accountable in our voting for their action or inaction on material governance matters.

How do you take asset owners’ views into account?

We spend a considerable amount of time talking to our clients, engaging with them directly to hear their views. We’re very conscious of the fact that we’re managing somebody else’s money, and it’s our job to make sure those asset owners have choices and that we’re meeting their expectations in terms of them achieving their desired outcomes.

Describe a typical engagement…

When we approach companies for a conversation, we know exactly what we want to discuss and what we would like to achieve. When we talk to the board, in the vast majority of cases it’s the Chairman. Depending on the topic, we would also talk to remuneration committee members or sustainability committee members and, if necessary, the CEO or CFO. I must point out that no nonpublic information is shared in these meetings. There are stringent laws and regulations that investors are required to abide by in this respect. We’re clear that the information must be publicly available to all investors.

How do you measure what you’re achieving through these conversations?

It depends on the issue. Some topics are more short-term in nature than others. For example, if we feel there’s a disconnect between executive pay and performance, we would expect boards to address that by the next shareholder meeting, so within a 12-month period. Sustainability or climate issues, on the other hand, are not going to be addressed in 12 months, yet investors will expect to see progress year-on-year, and that progress will be monitored over time. Monitoring progress over time and reporting on it is something that the investment industry needs to get better at, looking for ways we can communicate more clearly what all of this stewardship/engagement activity is achieving. This is something that the U.K. Stewardship Code is looking to capture through its reporting on outcomes from 2020.

How can progress on environmental sustainability be better monitored?

One of our engagement priorities is to factor “Environmental Risks and Opportunities.” So, we look for companies to disclose their approach to climate-related risks and their transition to a lower carbon economy, using the recommendations of the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) as benchmarks. Good quality, material disclosures enable us to make more informed voting decisions and are key for us being able to monitor progress. We consider progress in the context of the company’s current situation, its business risks and opportunities, and its ability to act.

“We spend a considerable amount of time talking to our clients directly to hear their views”

Some point out that two-thirds of the $7 trillion that BlackRock manages are in passively managed index funds, and some of the activities you’ve just described apply more to actively managed funds.

I deliberately don’t use the word “passive” because, even though we are index tracking, there’s nothing passive about the considerable amount of time BlackRock’s stewardship team spends engaging with companies to address concerns and prepare for informed voting. Besides, index-fund clients who are pension savers, charities, endowments, foundations and sovereign wealth funds have long-term orientations, and, as shareholders, they expect us to encourage the companies they’re invested in to consider a range of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) issues, including culture and purpose, in line with their long-term goals.

How do you monitor culture?

When engaging on strategy, purpose and culture, we normally discuss a company’s plans and policies and their implementation with management. We typically meet with one or more directors, possibly with management, to discuss the board’s role in counseling and holding management to account. Strategy, purpose and culture are more nuanced than many aspects of governance. Some companies publish clear, insightful explanations of their long-term strategy, purpose and culture, and we’d like that to be the norm. In their absence and/ or when we have concerns, we believe that engagement is preferable to voting to communicate expectations to the company.

I sometimes hear comments from companies that investors never ask about culture. Frankly, we don’t have to ask, “What’s your culture?” Culture influences both the “what” and “how” of the business, and some business decisions can be a litmus test for corporate culture. For example, a conversation with the board about how they determine executive pay. Or a conversation about the workforce and how boards are considering employee voice at the board level. Many companies say, “Employees are our greatest asset.” Then I ask, “What does that mean in practice?” And if they tell me I should talk to HR, then that’s a disappointing indication, because I would expect the board to engage in that conversation in a very meaningful way. The same goes for questions around strategy and how much the perspectives of different stakeholders are taken into account.

How do you see this field evolving?

We expect that asset owners will continue to hold companies to account on ESG issues, in addition to financial performance. I note that conversations between companies and investors are getting better. Increasingly, boards recognize it’s part of their job, and useful for them, to talk to their investors and hear their views, especially around topics of a long-term nature, such as the environment, human capital, corporate governance and pay, to name a few. This wasn’t the case, even in some large European markets, until very recently.

In engaging with companies, it’s not about us telling them what to do, but rather sharing experiences and different perspectives, and forming a view on what works. The whole investment and stewardship ecosystem is changing fast. But, with the European Union Shareholder Rights Directive II, the U.K. Stewardship Code and other directives designed to push corporate governance to the next level, the direction we’re traveling in is clear: higher expectations, greater transparency and more rigorous standards.

Board basics

03New paradigms in purpose, ownership and engagement

The board of directors is meant to be a collegial body, yet that’s not always the case. To function properly, everyone needs to understand what they’re there for. Do you?

4 Responsibilities for the Board

In some countries, these are split between different bodies (e.g., steering is separate from supervision & control, as in Germany’s two-tier board system).

1) Steering the organization

Discuss the vision and purpose of the organization. The CEO is typically selected on the basis of the collectively stated ambition. The CEO that the board has selected will work out a strategy, together with the executive team, and the board endorses it and approves the resources to put it into action.

2) Supervision & control

Boards used to control only for results; now they’re controlling for risk (e.g., violation of environmental regulations).

Resources: What’s management spending money on?

Investments: How much money is needed and where will it come from?

Behaviors: Are we obeying the law, and do we know what’s permissible regarding the acceptance of gifts, for example?

Compliance: Is there a dedicated compliance officer who reports to the board?

3) Following norms & standards

The CEO may set these, but the board must endorse them and make sure they’re being adhered to.

4) Assuming responsibility

If there’s a violation, the board is ultimately responsible. In some cases, individual directors can be held personally liable.

Why might you be asked to join a board?

- You represent a key shareholder or stakeholder.

- You have a reputation for reliability or independence.

- You bring specific know-how or capabilities…

- BUT remember you’re there to engage in general discussions, not to hold forth on your one area of interest.

Am I a good director?

- Do I add value?

- Do I make sure that the company has the right people on the board and in the management team to ensure its future sustainability?

- Do I contribute to the future of the company?

- Do I speak my mind?

What to do with board members who don’t talk?

- Take a step back to analyze: Why is this happening? Why is that person here? Typically, board members represent an interest: you need to figure out how to leverage that.

- 2 practical actions: (1) Make the order of intervening a random process. (2) Appoint discussants who have to read up on a topic beforehand and come prepared to lead a discussion on it.

Sources of conflict

- CEO is too dominant.

- Differing opinions about strategies and results: the best thing a board can do is call time on something that’s not working.

- Unhappy shareholders.

- CEO dissatisfied about remuneration.

- Directors who undermine the CEO by talking to the press and analysts.

There’s a mathematical relationship between the number of board members, the number of times you meet, and the number of topics that can reasonably be discussed. Think about that when planning the meeting agenda. There’s nothing worse than advocating that a decision be made during the meeting but then having to postpone it because you ran out of time. That wastes everyone’s time.

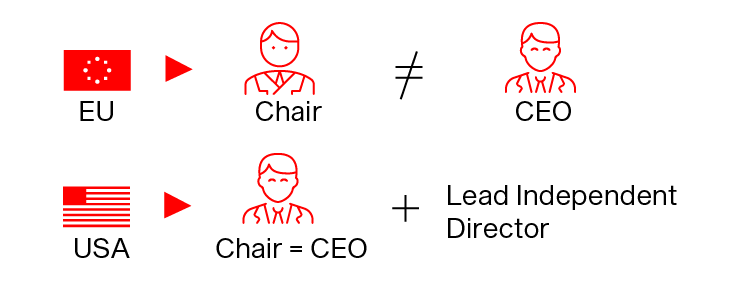

EU vs. USA role differences

Source: Based on the Executive Education lecture “How to be a good director,” delivered by Herman Daems, visiting professor of Strategic Management at IESE and veteran director of multiple boards around the world.

Herman Daems: “Ask the tough questions and come prepared”

04New paradigms in purpose, ownership and engagement

Herman Daems is Chairman of BNP Paribas Fortis and Domo Investment Group, among others. Having sat on the boards of numerous companies on both sides of the Atlantic, Daems has experienced firsthand the changes that have swept the boardroom, which he documents in his book, Insights from the Boardroom.

Company boards meet just a few times a year, but the challenges they face are non-stop. Here, Herman Daems discusses the board’s shifting roles and responsibilities, and what it takes to be a good board member.

How has the role of the board changed in recent times?

The traditional job of the board – to supervise and control management resources – has grown significantly. It used to be that boards controlled almost exclusively for results. Now they’re increasingly controlling for risks and management behaviors – for compliance. Is there cheating? Are we following the laws?

We tend to think of banks in this regard, because theirs is the most visible sector where compliance has gotten more onerous, but it’s happening across all sectors. The chemical industry also has stricter rules: salespeople have to be trained to know what is and isn’t permissible to say to other salespeople. The same goes for pharmaceutical companies, as well as the Nestlés and Unilevers of this world. There are more and more rules that a company has to comply with.

And while the board doesn’t actually do that compliance, it does have to make sure that all of the firm’s compliance functions are being properly executed, that there’s a person and an office responsible for it, and the board must hear, at least once a year, a report on compliance.

Part of this is being driven by a wider shift that’s happening across the business world, from being solely profit-driven to also being purpose-driven. The board has the added challenge of more involvement with society while at the same time protecting the horizontal line. This is something really new.

How does the experience of sitting on a board differ from one company to another?

It depends on the context, particularly the ownership structure. There’s a world of difference between, say, sitting on the board of a large, listed company with thousands of disparate shareholders, many of whom have no interest in interfering with the board’s decision-making, and sitting on the board of a company owned by a single family in which you may have very little say.

Serving as an independent director of a startup is yet another story: here, you may need to act more like a referee between the founding entrepreneur and the VC firms involved, who may not see eye to eye on which direction to take the business.

Then, there are other factors that can lead to differences, such as: the composition of the board and the personalities of its members; the laws and regulations in place where the company operates; and how authority is allocated.

In Europe, the Chairman and CEO tend to be two separate people, whereas in the United States, the Chairman and CEO are often the same person. Personally, I don’t think that’s a good practice. And increasingly the U.S. must think so too, because they’ve created a new function, the Lead Independent Director, to essentially monitor that the CEO as Chair is performing the role to the board’s satisfaction.

Where do you see boards frequently having difficulties?

One is around strategy. People often think the board decides on strategy. That’s not true. The board approves the strategy. The CEO that the board has selected will work out a strategy, and it’s the board’s job to look at it and decide whether they believe in it or not. They ask the tough questions: “How are you going to do this? How much money will you need? What are the investment requirements? Where is that money going to come from?” That’s a big difference.

So, while it’s not your job to set the strategy, it is your job to apply the brakes if that strategy isn’t working. Managers are prone to carry on: “Just give us a few more months and it’s going to work.” At some point, someone has to step in and say, “Stop. You’re going to try something new.” That’s the board’s job.

“Dissatisfaction about remuneration can lead to conflict in the company and unhappy shareholders. Don’t underestimate this”

Deciding on acquisitions is another big mistake I see boards make. I’m convinced that so many acquisitions fail because the board overpays and is led in the wrong direction by the management who get so excited by “this great strategic opportunity” that they forget to think about how much it’s going to cost. It’s your responsibility, as a board member, to protect the resources of the company and think about these things.

Another difficult topic is remuneration and variable compensation. Honestly, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve spent talking with frustrated CEOs trying to pressure me into giving them more money. Dissatisfaction about remuneration can lead to conflict in the company. And it can lead to unhappy shareholders. Don’t underestimate this.

What about with the board members themselves?

One thing you have to understand is that boards need people with broad orientations. So, if your focus is narrow, you shouldn’t be on the board. I’ve had people come up to me and say, “I’m really outstanding in logistics and I’d like to join the board.” You’re not the right person. We don’t need the best logistics manager in the Western world. Apart from the fact that the logistics person in the company is probably going to be thinking, “Great, now I’m going to get an additional boss on top of my CEO,” no one is really interested in having a board member who can only talk about one thing. If you can’t talk about the results and the performance of the company in general terms, and about the market conditions, you’re worthless.

Besides being able to talk about more than one thing is simply being able to talk. Consider the banks: why did they go under? If you look at their governance before the crisis, most of them would get five stars: they had separation of powers, they had the right committees. They had everything except people who spoke their minds. People kept quiet and accepted whatever the management told them.

One of the really important things for you, if you join a board, is to speak up and express your opinion – not to start a fight, but to really state what you think.

What do you do about those people who just sit there and don’t talk?

As the Chairman, I’ve done two things. First, I make the order of intervening a random process. I don’t let the person with the biggest name speak first. I make sure someone else gets the floor first. This changes the debate.

Second, I appoint first discussants. Days before the meeting, the secretary sends round a list of topics to certain board members who will be responsible for leading the discussion on that topic. This has a number of advantages. First, they read that document very carefully. Second, they express an opinion. Then the others can respond to that opinion.

Any other advice?

When speaking your mind, be courageous, but remain friendly. If you’re coming in with an attitude of, “I’ll tell them,” it’s not so good. You challenge, but in a friendly way: “Why are you doing this?”

Sometimes asking even the stupid question forces everyone, especially the executives, to really think through how they’re presenting certain things. If you feel that you need to know something, it’s your duty to ask for it. Don’t be afraid to ask for information that you think you need to have.

Finally, there’s nothing worse than having to postpone an important decision until the next meeting because “I forgot to read this.” That’s not stimulating for the executives who were counting on this board meeting to get approval for what they’re doing. As a board member, you’re supposed to do your work, so please, please, please, come prepared.

Next on the agenda: digital disruption

05New paradigms in purpose, ownership and engagement

Is technology also transforming the functioning of corporate boards? Is it having any effect on shareholder monitoring?

Nowadays, few business topics draw as much public attention as digital disruption. Web-based application programming interfaces (APIs), smartphones, blockchain technology, machine learning and data analytics, among many other innovations, are giving rise to the emergence of new business models and transforming the ways firms operate and interact with clients, suppliers and other stakeholders. In this context, a natural question is whether this wave of technological disruption is also transforming corporate governance.

Recent survey and anecdotal evidence suggests that digital disruption is a major concern for boards. But is technology also transforming the functioning of corporate boards? Is it having any effect on shareholder monitoring?

Not much, one could conclude at first glance. However, even if that were true, such a conclusion runs the risk of ignoring important changes that are yet to come. Some of these changes relate to the functioning of corporate boards. For example, Netflix recently opened access for its directors to all the data on the firm’s internal shared systems.

Of course, one could argue that there is only so much information a director’s brain can process. But advocates of technological change would counter that this is not necessarily a problem. Artificial intelligence and machine learning can help directors by identifying correlations and by producing better forecasts.

Not only that: computer-based textual analysis can help identify mismatches in wording and inconsistencies in numbers. In addition to enhancing access and quality of information, technology could facilitate the preparation of board meetings by automating mundane tasks.

What about shareholder monitoring? Can technology enhance shareholders’ empowerment? Consider the application of blockchain technology to the register of corporate shares. This innovation would enhance transparency. The register would be publicly observable and changes recorded instantly. This is possible through a process of computerized verification of transactions. Moreover, such a register would increase stock liquidity by shortening the time required for executing and settling securities trades.

Technology opens new ways to fight opportunism and enhance the role of stakeholders in corporate governance day one

This is important, because ownership transparency and stock liquidity go hand in hand with shareholder monitoring. Let us remember why.

First, liquidity is at the heart of an important mechanism through which investors put pressure on firm managers – the possibility of “voting with their feet” (i.e., selling their shares).

Second, a transparent share register could attract some investors (e.g., institutions) and repel others (e.g., raiders). This matters because investors often differ in economic interests – for example, in terms of risk preferences or investment horizon – as well as in their ability to influence top corporate managers.

Technology also opens new ways to fight managerial opportunism. Consider a firm disclosing its ordinary business transactions on a public blockchain. This disclosure would result in real-time accounting (i.e., instantaneous financial information), which would facilitate the monitoring of firm performance and make manipulation more difficult.

Similar technological developments could limit other types of managerial opportunism. For example, a blockchain register of insiders’ trades could reduce the profits from misusing private information, as outsiders would be able to observe managers’ trades in real time.

Can technology improve shareholder voting? Consider a firm holding a virtual shareholder meeting with a remote voting system. Remote connection would likely result in higher shareholder participation. Remote voting would address issues such as incomplete distribution of ballots, incorrect voter lists and problems in vote tabulation.

Technology could also enhance the role of stakeholders in corporate governance. Customers could influence firms by sharing their views on social media platforms. Suppliers could protect themselves from client opportunism by using “smart contracts” – for example, a supplier selling a device that automatically stops working if the payment is not done before a certain date.

So, can we conclude that technological disruption enhances corporate governance? Not so fast: technological disruption also raises concerns. Some – such as hacks and privacy breaches – are obvious. Others are less evident, such as the greater transparency inducing short-termism and, by discouraging potential raiders, managerial entrenchment.

All this calls for a careful consideration of the potential unintended consequences of technological disruption. But, as with any innovation, assuming certain risks is par for the course.

Gaizka Ormazabal is an associate professor of Accounting & Control and academic director of the Center for Corporate Governance (CCG) at IESE. To find out more about the activities of the CCG and to subscribe to its newsletter, contact ccg@iese.edu.

Unique challenges for boards of directors

06New paradigms in purpose, ownership and engagement

What should boards of directors do during these exceptional times?

By Jordi Canals

The world economy has been put under tremendous downward pressure with the coronavirus pandemic. In many countries, economic activity has been reduced to a few vital activities. Companies are under enormous stress. What should boards of directors do during these exceptional times?

Under normal circumstances, the main role of the board of directors is to help and supervise the CEO and senior management to develop the company for the long term by serving customers well and creating value for all. Companies need to serve customers in a unique way, and to do so, they should invest in their people, in capabilities, and in intangible and tangible assets. The nature of these investments requires a long-term horizon, and boards should oversee this process.

In this time of crisis, boards also have a special duty: to support the CEO and senior management team so that they focus their efforts on guaranteeing the firm’s survival. Firm survival may be under real threat now due to a variety of reasons, including people’s health as a result of infections, cash constraints, supply chain restrictions and lockdown conditions.

In this context, the following reflections for boards may be useful. First, board members should ask the Chair and CEO to convene a formal board session as soon as possible to assess the current strength of the company. The information required to conduct a good assessment may be incomplete; nevertheless, just as the CEO and senior management team should be working together on strategy issues, the current crisis makes the exercise of sharing and discussing these issues with the board even more urgent. The board should understand well the firm’s weak points, risks and financial constraints, including cash constraints. The board should encourage the CEO and CFO to be working with the banks to make sure that the company has the liquidity it needs to operate.

The board of directors can be extremely helpful in supporting the CEO in organizing the company for the crisis

Some attributes of the firm’s strategy will need to change. In many industries, new opportunities will emerge, partly as a result of changes in consumer preferences. Companies will need to adapt to new customer behavior in order to serve them well. Experienced board members can contribute a lot to the board and the company as a whole in these very important discussions.

The board of directors can be extremely helpful in supporting the CEO in organizing the company for the crisis. The formal organizational structure may need to change, and new teams may be needed to tackle new challenges. While these areas fall under the CEO’s responsibilities, the board should make sure that the CEO has the time and right organizational support to oversee all these matters. Displaying exemplary professional behavior, the CEO should serve as a vital reference point, providing meaning and purpose for employees, customers and other valuable stakeholders.

It’s particularly important for the board in this time of crisis to pay careful attention to the firm’s reputation. Through the quality of its governance decisions and the professionalism and fairness that the board and the top management display in their behavior, the firm’s reputation and credibility for good governance can be enhanced, even if the company needs to make very difficult decisions. This is a very special time, during which boards of directors have a unique role: to help their companies survive and turn them into respected institutions. Boards should live up to this challenge.

Jordi Canals is a professor of Strategic Management and Economics, president of the Center for Corporate Governance (CCG) and holds the IESE Foundation Chair of Corporate Governance.

Watch: The Changing Role of the Board of Directors

This Report forms part of the magazine IESE Business School Insight #155. See the full Table of Contents.