The Green Deal

01The Green Deal

How green stimulus may be the key to cranking up economic recovery after the crisis.

Climate neutral by 2050. That is the overarching goal for Europe, formally launched in December 2019 as the European Green Deal.

But that announcement came as Europe enjoyed its highest employment rates ever. And we all know what happened soon after: COVID-19 began wreaking havoc. Yet, amid 2020’s twin health and economic crises, the European Commission is doubling down on its commitment to sustainable, green growth, unveiling a €1.8 trillion ($2.2 trillion) stimulus fund to keep the recovery on the Green Deal track.

Over the past year, we have seen progress on various fronts: a proposed Climate Law, strategic plans for key sectors, including sustainable finance, and various tax mechanisms. Still, “we are only at the start of what is going to be an incredibly complicated transformation process,” Frans Timmermans, Executive Vice President for the European Green Deal, told the European Business Summit in November 2020. He was excited to see things “moving in the right direction internationally. And if international momentum is created, that will allow European leadership to actually achieve something on a global scale.”

Everyone is a winner

There is some evidence of building momentum. In September 2020, China’s president, Xi Jinping, pledged to reach carbon neutrality by 2060, a major move from the world’s top polluting nation. In November 2020, the U.S. president-elect, Joe Biden, pledged not only to rejoin the Paris Agreement that the United States had left under the Trump Administration but to reach net-zero emissions by no later than 2050 – an about-face for the world’s second biggest polluter. In addition to those carbon heavyweights, Japan, South Africa, South Korea and the United Kingdom also recently announced net-zero emissions by 2050. Whether anticipating the 26th U.N. Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) set for November 2021 in Glasgow, or desperate to get out of the pandemic crisis, the world seems to agree that rebuilding is necessary – with the sustainability of the planet holding the key.

The Green Deal is Europe’s man-on-the-moon moment

In the words of the European Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen, this is no less than another man-on-the-moon moment. Just as the Space Race of the 20th century pushed scientific and technological advances on many continents at once, the 21st century Green Race has the potential to push many ahead at once for the good of all. Which economies will get to net zero first? Who will lead the transformation? As Timmermans told the European Business Summit, “Whoever ‘wins,’ everybody goes in the right direction.”

Of course, everybody means everybody moving in the right direction, not just governments and politicians but companies, investors, citizens and a multitude of other stakeholders. Because while “decarbonizing Europe can have broad economic benefits, including GDP growth, cost-of-living reductions and job creation,” getting there won’t be easy, as a McKinsey report made clear: A net-zero transition could create an estimated 11 million jobs, yet 6 million would be eliminated. That is why a concerted effort is necessary, so that people can be retrained and reskilled for new positions that McKinsey predicts will open up in renewable energy (1.54 million), agriculture (1.13 million) and buildings (1.1 million), for example.

So, what’s happening on the front lines and, crucially, in the growing field of sustainable investing, where the shift is already underway?

Green stimulus

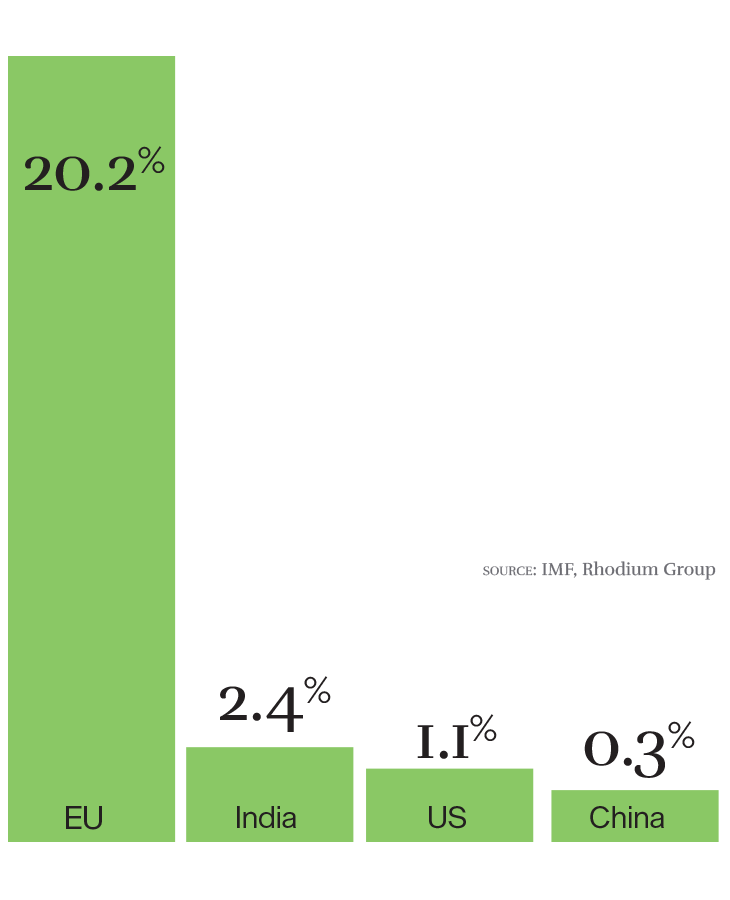

Among the world’s four largest economies and largest greenhouse gas emitters that have launched stimulus programs to kick-start their recoveries post-COVID-19, Europe’s is the greenest, with over 20% of its stimulus plan directed at green, climate-related initiatives, compared with 0.3%-2.4% in the stimulus programs of China, India and the United States, where the “Green New Deal” is a politically loaded term.

Powering forward

The five sectors currently responsible for most of the European Union’s greenhouse gases are transportation, industry, power, buildings and agriculture, according to McKinsey. Europe’s power sector may be the first to achieve net zero, thanks to renewables, particularly wind and solar. As those technologies are increasingly deployed over the next two decades, renewable production and storage capacity will have to be rapidly scaled to keep up with demand from other sectors, especially industry.

IESE’s Massimo Maoret has written case studies on key players in the transformation of the power sector, including the Danish company Ørsted, now the world’s largest offshore wind producer, and the Italian energy infrastructure company Snam, which operates Europe’s biggest gas pipeline. Even before the European Green Deal launched, Snam was looking to align its gas pipeline-and-storage business with future sustainable energy needs. For Snam’s Executive Vice President for Corporate Strategy and Investor Relations, Camilla Palladino, “Net zero as a target really focuses the mind. You have to work backward from the goal.”

She explains: “We have moved from what might be called an ‘every little helps’ approach to one in which the harder, longer term sustainability goals are at the forefront. Until we had the net-zero target, the really hard bits of the equation weren’t being addressed. Instead, we would put one foot in front of the other, trying to do the next best thing.”

Net zero as a target really focuses the mind

Palladino refers to a story about Bill Gates, who, whenever he heard an idea for what more could be done to stop global warming, would pointedly ask, “What’s your plan for steel?” The reason is that steel and other ubiquitous materials like cement and plastic are major greenhouse-gas contributors, and the real plan he felt was needed was one that came up with affordable zero-carbon versions of those everyday offenders.

Now, if you ask Palladino, “What’s your plan for steel?” she will tell you, “Clean hydrogen.” Yes, it will take years of proof-of-concepts and big pilot projects before it can be seriously ramped up. But no more baby steps. The Green Deal has made hydrogen a priority, with hundreds of billions of euros in investment expected well ahead of 2050. That means Snam and its industry partners can start “pushing hydrogen down the learning curve now” in a much bigger way, “to be ready for it to take its role in the energy mix by 2050,” of which green gases are expected to account for more than a quarter.

This illustrates how the Green Deal may be just the impetus certain industries need – with a goal, regulatory and public support, public and private investment – to help reach those “hard-to-abate sectors,” says Palladino.

Where the money is

In addition to the public sector concentrating minds toward specific goals, responsible investing also plays an important role in reallocating capital toward “the clear and present danger of climate change. In addition to public initiatives, we are going to need all the private money we can gather. We need to invest in a way that reduces this threat as much as possible,” says IESE’s Fabrizio Ferraro, who researches responsible investing and recently moderated a panel on the topic as part of the Ship2B Impact Forum.

Ship2B is an organization dedicated to promoting impact investing in Spain. Its co-founder, Xavier Pont (IESE MBA ’02), believes that government and philanthropic actions are not enough to solve the existential threats facing humanity, and that we need to mobilize the might of the capitalist system – which moves more money than the public and philanthropic sectors combined – to boost impact investing. “That is the real way to generate social impact.”

The good news: There is evidence this is happening. Responsible or ESG (for Environmental, Social and Governance) investing has grown to represent more than $30 trillion in global assets under management.

We need to mobilize the might of the capitalist system to boost impact investing

Participating on the panel with Ferraro was Miguel Nogales, Co-Chief Investment Officer and a founding partner (along with former U.S. Vice President Al Gore) of Generation Investment Management, which seeks to invest in and engage with companies that have long-term orientations and whose goods and services are consistent with a low-carbon, equitable society. “The idea of climate change in investing is usually framed as risk,” said Nogales, “but really it’s an opportunity.”

Nogales sees the current moment as a rare and ripe one for investors, where the stars are perfectly aligned: “There needs to be an enormous and rapid transition in everything – from power and mobility to what we eat and what we wear – and that transition has to happen fast and it will have broad support, both regulatory and financial. As an investor, that is an amazing setup.”

For investors in Europe and elsewhere, one initiative worth watching is the EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities. Despite its opaque-sounding name, this Taxonomy matters because it will cover disclosure requirements in relation to the Green Deal’s key environmental objectives for a broad range of equity and debt-based financial products. Implementation is planned for 2022.

Investing with impact

Michael Canfield, Portfolio Manager, Man Group “We have a very loud voice with the C-suite and can enact real change”

Maria Laura Tinelli, Director and Co-founder, Acrux Partners “Initiatives like the Green Deal create the conducive ecosystem and the opportunities necessary for the market to move forward: This makes the difference”

Miguel Nogales, Co-Chief Investment Officer, Generation Investment Management “Climate change in investing is usually framed as risk but really it’s an opportunity”

While some may balk at added reporting requirements, alignment with the Taxonomy could open doors to more financing while signaling to investors where to invest responsibly. It could also signal where to invest resiliently. Rui Albuquerque (Carroll School of Management, Boston College) and co-authors found that companies with higher environmental and social scores tend to experience softer landings when exogenous shocks – like the COVID-19 pandemic and consequent stock market crash – occur. And not only do ESG-oriented investors experience less return volatility during a crash, they also see higher stock returns than others, a finding backed by other studies of resilience in crisis.

The pressure to apply the Taxonomy will extend well beyond Europe, with U.S.-listed companies already studying up. It also has a cascading effect on other regions of the world – a point made by Nogales’ fellow panelist, Maria Laura Tinelli, director and co-founder of Acrux Partners, a London-based impact investment advisory firm operating in Latin America. “We are beginning to see how regulations passed in the EU – which is the hub for more proactive, progressive regulations to be issued – filter all the way down to a country like Brazil, Argentina or Chile in terms of which standards it chooses to adopt.”

Despite these pushes in positive directions, real change will take something more: “Investors alone won’t cut it,” added Tinelli. “You can have very progressive investors or firms, but if they are not appropriately accompanied by government regulation and proactive actions by the ecosystem as a whole, investors or companies alone cannot deliver on the promise.” Here, again, is why all-encompassing initiatives like the Green Deal are so important, in that they “create the conducive ecosystem and the opportunities necessary for the market to move forward. This makes the difference.”

That said, another panelist – Michael Canfield, Portfolio Manager of Man Group – stressed that the role of investors in this ecosystem should not be understated. “As investors, we have a very loud voice with the C-suite, and we can enact real change if we make the effort to do so.” Nogales agreed. In his experience, “CEOs really listen to investors, perhaps more than you might expect.” For companies outside of countries with formal climate goals, shareholder activism may be another path toward change.

Green bonds: funding action

In the fast-growing realm of ESG investing, there is an asset class that is becoming particularly important: green bonds. The beauty of green bonds is that they allow all types of investors, be they individuals or institutions, to invest in pro-environment, pro-planet projects. That is to say, bond buyers are investing in actions, not business profits or potential. Even fossil fuel companies can issue green bonds if they use the proceeds to clean up their acts, environmentally speaking.

Since 2007, when the European Investment Bank issued the first widely recognized green bonds for green goals, the market has steadily grown. In fact, according to Moody’s, proceeds reached $258 billion in 2019, up from less than $1 billion a decade ago. In September 2020, Germany joined the Netherlands, France, Sweden and Poland in launching a green bond, which, according to the Financial Times, was five times oversubscribed, demonstrating investors’ appetite for more.

Where investors lead

EU-based institutions and asset owners are more likely than others around the world to commit to responsible investing, as measured by the number (55%) of signatories of the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) – although they don’t control the most Assets Under Management (AUM).

EU

55%

AUM $32 trillion

U.S. & Canada

24%

AUM $46 trillion

Rest of world

21%

AUM $11 trillion

SOURCE: PRI Signatories Reporting in 2019. “ESG and Responsible Institutional Investing Around the World: A Critical Review” (2020) by Pedro Matos, Darden School of Business.

Naturally enough, the EU plans to fund a substantial portion (30%) of its green recovery with green bonds. Expected to raise up to €240 billion ($290 billion), the EU green bonds slated for sale in 2021 would be the world’s biggest issuance to date, nearly doubling the current green-bond market. That said, there is some question over whether the Taxonomy, linked to a proposed Green Bond Standard, will be ready in time. In any case, the EU looks likely to open the spigot and set standards in the coming months.

This is the train to catch

With the coronavirus halting flights and shuttering parts of the economy, greenhouse gas emissions dropped. The extreme change of habits on a global scale provided a taste of what is required to rein in climate change. But it will take many years of emission cuts comparable to those we experienced in 2020 just to reach the Paris goals, Nogales pointed out. The way forward is not to give up but to steer economic growth, accelerate change and innovate in bold, new directions.

Putting it another way, Uli Grabenwarter – a lecturer at IESE and Deputy Director of Equity Investments at the European Investment Fund working with impact investing – noted: “One feature of social business models in a crisis environment, like now, is that you will not have to worry about not having a market. That creates natural pathways to growth and increases the odds of obtaining funding.” Solving wicked problems is what entrepreneurs were born to do.

And while the coronavirus pandemic has dominated 2020 headlines, a green recovery offers hope to problem-solvers across industries. “This is an opportunity that happens but once in a generation, and it is happening now,” the Spanish economist Miquel Puig Raposo told IESE alumni in a recent online learning session. “This is the train to catch.”

We have a moral duty as managers to do right by others and the world

“Why do we think sustainability is important? Why do we want to pay people a good living wage?” IESE Dean Franz Heukamp asked in a recent interview. “Because of our moral obligations as people, recognizing that business is, in essence, a community of people serving other people within a wider world that is, again, another community of people. And we need to think about how our actions affect those other people. It not only makes good business sense to nurture the wider ecosystem upon which businesses depend, but we also have a moral duty as managers to do right by others and the world.”

Putting people alongside planet and profit is the famous triple bottom line for business – a view that seems to be gaining traction. The most recent Korn Ferry survey of European CEOs reported that nearly two-thirds (62%) of them anticipate that the shift from a single focus on profit to the triple bottom line will be the mainstream view by 2025.

Paul Polman, the former CEO of Unilever, is one corporate leader who believes the shift is long overdue. Speaking at a conference organized by the IESE Center for Corporate Governance, he noted that “the way the global economic system has provided wealth is unsustainable. Endless growth cannot be perpetuated on a finite planet. In the last 40 years, humans have done historic damage to the planet. The COVID crisis is just a symptom of the shortcomings of the current system, showing that healthy people cannot thrive on an unhealthy planet. Just as U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt created the New Deal in the 1940s and pivoted the U.S. to prosperity, the world needs another New Deal.” Which is precisely what we have now.

While more of Europe’s private sector leaders may be ready by 2025 to mitigate risks associated with exogenous shocks – from frequent and intense droughts, floods and wildfires to pandemics – and achieve prosocial goals, there’s no reason to wait any longer. Plotting actions now, as we enter 2021, in order to unlock green recovery funds and make green investments, can put you and your business ahead of the curve.

What’s the view from the C-suite?

71%

want to lock-in climate change gains made as a result of the pandemic

65%

say managing climate-related risks will play a part in whether they keep their jobs over the next 5 years

+2 percentage points

The connection CEOs feel to a societal-driven purpose has grown stronger since the crisis began, going from 77% to 79% during 2020

SOURCE: KPMG 2020 CEO Outlook: COVID-19 Special Edition

Why greenwashing won’t wash

Whatever you decide to do in relation to the Green Deal, make sure it’s authentic, because the consequences of merely giving the appearance of being an environmentally friendly company on the outside without making the necessary investments or changes on the inside – the practice known as greenwashing – can be severe, both in terms of your firm’s reputation and its bottom line. That’s the message from IESE’s Pascual Berrone, author of the book Green lies: How greenwashing can destroy a company (and how to go green without the wash).

Your environmental efforts must be genuine, insists Berrone. Jumping on the Green Deal bandwagon before you have gotten your house in order – not least gotten the support of the CEO and board – is risky. If your green credentials are shaky, best to hold off until you are in a more credible position. If not, given the power of social media and activist shareholders, any fakery will be quickly exposed and punished.

The only time “faking it till you make it” might work is if it serves as an in-house tool to drive the organization toward deeper engagement, as Jeanologia CEO Enrique Silla explains: “Greenwashing is a lie, but it can also be useful. I daresay that the person who begins with greenwashing will soon realize that planet and profitability are inextricably linked, and the more they start to deal with others who are genuinely walking the talk, they will likewise be transformed.” (See the full interview with Silla later in this Report.)

That said, he concurs with Berrone on the safest way forward: Identify how sustainability relates to the way your company creates value; then adjust your operations, investments, governance structures and metrics accordingly. In short, start putting your money where your mouth is. It’s also important to dialogue with your stakeholders – not just your suppliers but consumer groups and policymakers – and partner with industry peers. Only after you have done all that should you even think about tooting your horn.

“The era of greenwashing is coming to an abrupt end,” notes investor Miguel Nogales. “The time when you could say, ‘Just come up with a nice report with trees on it to get the activists off my back’ is really over. And that’s a good thing.”

Frans Timmermans: “It can be done”

02The Green Deal

Frans Timmermans is Executive Vice President for the European Green Deal of the European Commission.

As the pandemic forced our world to a grinding halt, it offers us a chance to take a step back and reflect: What world do we want our children and grandchildren to grow up in?

The European Commission, in response to European government leaders’ request to chart the EU’s long-term course, is working to make Europe the world’s first climate-neutral continent in 2050.

The European Green Deal is our growth model, our plan to invest in innovative technologies, new markets and sustainable jobs. We will cut at least 55% of greenhouse gases by 2030. Our Climate Law will put our targets for 2030 and 2050 into law. We do so to provide as much long-term predictability and stability as possible, especially now.

In the next couple of months, the European Commission will prepare the legislation to support our climate targets and to deliver regulatory consistency. This is exactly what many in business have been asking for, and rightly so. Because you know the change is coming. Many companies, especially the largest ones, have even recognized it much earlier than us politicians. Investors are increasingly switching their portfolios.

Make no mistake: What we will do on the European emissions trading system, on renewable energy, in automotive – all these steps will imply structural changes in many industries. We are at the start of an incredibly complicated transformation process. It will require enormous efforts, but it can be done.

We are about to spend enormous amounts of money to build back better. This is a huge opportunity to invest massively in Europe’s recovery. We have one chance to get it right, to spend it on where we want to be tomorrow. Let’s not waste it by locking ourselves into soon-to-be-obsolete technologies and outdated carbon-based business models. It would be a dereliction of duty if we were to invest in sectors with a limited future, only to create stranded assets and economic problems further down the line. Let’s focus our recovery on our common future instead.

At the end of the day, this is not about saving the planet. It will do fine without us. This is about a healthier and better life for all of us. Climate change will not stop because we close our eyes. Not acting is no option.

Pledges for business leaders

03The Green Deal

As part of the World Economic Forum’s Great Reset initiative, the CEO Action Group, representing senior executives from 30 leading companies, calls upon businesses to step up their commitment to the Green Deal in these important ways.

1. Commit to the goal of making Europe climate-neutral by 2050

Set meaningful, ambitious, long-term targets for your own path toward 2050, embracing new production and work models as appropriate.

2. Ensure your HR policies are fair, inclusive and people-centric

Invest in education, reskilling and upskilling of the workforce, with a particular focus on youth, to ensure sustainable employment opportunities and hope for those who need more support in making the transition to the green economy.

3. Support green innovation

Ensure your R&D agenda allows ample room for experimentation and collaboration with industry peers on other continents to drive market development and scale up offers in areas identified as priority for the green economy, including investing in lower carbon technology and innovation.

4. Consider changes to your business model

This may mean reassessing your use of resources, investing in the circular economy, redesigning some supply chains, adopting smart technologies and/or renovating buildings and other infrastructure to make them smarter and cleaner. All without compromising efficiency and competitiveness.

Read Build Back Better: How business model innovation can help your firm out of the crisis

5. Step up financial disclosure and transparency

Harmonize your reporting, rating methodologies and validation mechanisms in line with ESG standards and the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

SOURCE: Based on info from the European Commission and the World Economic Forum CEO Action Group for the European Green Deal.

See the above presented in video format or download it as an infographic from the button below.

Enrique Silla: “Caring for the planet is a fantastic business”

04The Green Deal

Enrique Silla is CEO and Founder of Jeanologia, creating sustainable, eco-efficient technologies used in over 60 countries for making jeans for Levi’s, H&M, Inditex and other leading brands.

When Enrique Silla founded Jeanologia in 1994, the idea of reducing water and eliminating damaging emissions and waste from denim finishing – one of the most polluting industries – was like “the lone voice in the wilderness,” he says. But he wasn’t to be deterred: “Caring for the planet is a fantastic business.”

Today, over 35% of the 6 billion pairs of jeans produced worldwide every year are made with Jeanologia technologies. And in five years’ time Silla hopes to see “the entire global production of jeans done sustainably and without polluting the rivers and seas of our planet.”

To this end, Silla believes the European Green Deal can play a leading role in transforming not just his own industry but many others that are taking their environmental and social responsibilities more seriously. Here, he explains how.

How do you see the Green Deal rebuilding the economy post-COVID-19?

There’s going to be tremendous government spending à la Keynes but instead of highways those funds will be destined for companies that put the planet first. Financial markets are also going to invest more in those enterprises that contribute to sustainable societies. We already see major investment funds excluding polluting sectors such as fossil fuel companies from their portfolios. This trend will only continue.

But the Green Deal is not just about releasing more money into the economy; it’s about releasing hope in our children, who look out onto a bleak world with fewer opportunities than their parents had and feel demoralized. I think the Green Deal and other likeminded initiatives around the world can help inspire a new generation to launch new kinds of businesses – and that energy, in the end, is what changes the world.

What about traditional businesses?

Innovating in a traditional sector or market isn’t impossible. A lot of smart and talented people gravitate toward startups in new sectors, but there are untold opportunities in traditional sectors, precisely because being traditional makes them ripe for innovation.

When we started, we stuck to two premises in deciding which technologies to develop. First, we prioritized anything that would reduce a negative impact on the planet. Second, any innovation had to reduce costs and enable us to become more efficient and competitive – because in the end that’s what our clients value. However, we would never embark on the second without the first. That’s the mistake some traditional businesses make: focusing on the second without considering the first.

You have to decide what kind of relationship you want to have with your clients: purely transactional (“You buy what I sell for a set price”) or a partnership, built on trust. I am much more willing to put my trust in a company that has some values and wants to serve society and the planet. You must have a purpose beyond reducing costs and making money. The planet has to be part of your business plan. That also gives your employees greater motivation to keep going and growing, in good times and bad. Taking care of the planet is no longer a source of competitive advantage; it’s a basic requirement. Whoever doesn’t incorporate the environment and ethics into their business will be out of the market in five years.

“Whoever doesn’t incorporate the environment and ethics into their business will be out of the market in five years”

So why is it so difficult for some executives to change their chip?

I think some resistance comes from the false notion that being sustainable is going to cost more, making their products more expensive and their business less competitive. Or they think it’s all well and good for European politicians but not for those who live in the real world. Transforming such thinking is a journey, and it starts, like building a house, with the foundations.

First, do something simple, like changing to LED bulbs, which will immediately lead to energy and cost savings. Then, take it a step further: Resolve that none of your production processes or the third-party products used in your supply chains will contaminate the environment, and strive to reduce your emissions, residual waste, water consumption and use of chemicals and energy in your production processes. This is what we are trying to implement across the entire textile sector through our Mission Zero initiative.

Once you’ve done that – which is already a lot – we get to the third point: system thinking. This is about changing the whole system, from the design to the execution of products and services, so that everything is conceived to be recyclable and eco-friendly and add value to society. And everything should be measurable, to track progress as the company evolves in ethical and ecological directions. It’s actually much easier than you think. Respecting the environment costs less than destroying it.

What changes can we expect to see in the next 10-30 years?

Digital technologies and artificial intelligence (AI) are fast changing the way we sell, from the physical world to online, and COVID-19 has accelerated that trend. And if we sell and consume differently, then we ought to be changing the way we produce. As consumers buy digitally, we should be analyzing their tastes and then only producing what we know will sell instead of trying to sell whatever we produce. This will generate enormous economies of scale, eliminating unnecessary inventories and working capital. That will have not only a financial impact but also an ecological one by reducing transport costs and waste.

In the future, I envision thousands of small urban factories in every city of the world that produce only for local consumption, with water completely eliminated from production processes, or at least fully recycled. It’s already possible for us to do this today. In fact, we’ve set up such manufacturing centers in Shanghai, London and Los Angeles. And in Nevada, the Levi Strauss factory is located right in the middle of the desert, to make a very visible point about not using water. I see a world with millions of such factories, collectively bringing about a supply-chain revolution.

This atomization and relocalization of production will facilitate the return of manufacturing to Europe, generating employment here. Although Europe has lost much of its manufacturing capacity – we’re never going to see huge factories of 4,000 employees in footwear, for example – we can see dozens of small urban factories of 20, 30, 50 or 100 employees, perhaps under the same investor. The labor costs in Europe may be higher but these would be offset by lower logistical costs. This is the paradigm shift I imagine for 2030-2050.

For this to become reality, we need the artisan working side-by-side with the technician. We call this person the TechArtisan: They maintain their product sensitivity while at the same time they’re able to analyze data and use AI not only to manufacture a product that sells but to have the capacity and speed to manufacture only those products that are proven sellers.

There’s a lot of talk about business resilience to get out of the crisis. What does this mean to you?

I think the word resilience has been overused in recent months, with some confusion. Before COVID-19, almost all CEOs and boards of directors prioritized growth and high EBITDA. Now, some companies have focused all their efforts on resisting just to get through the crisis, based on loans, and they think that’s resilience. But they’re mistaken, because it’s not a question of resisting long enough until things go back to how they were before, because the world won’t be the same again.

We need to transform our companies to be more agile, emerging from this crisis stronger and with a newfound purpose. That’s resilience. In this moment, the important thing is not growth or making as much money as possible, but preparing yourself for the new reality that’s about the come.

This time is different

05The Green Deal

Experienced executives, and anyone who bothers to learn about the history of sustainability, will be tempted to dismiss the recent wave of green enthusiasm as a passing fad. We did experience, in fact, a similar wave of societal and corporate attention to the environment, and more broadly the social responsibility of corporations, back in the 1970s, only to see it wane over the years.

But this time is different, and sustainability concerns are not just expressed by social movements and concerned citizens but increasingly come from corporate leaders. I believe we are at the tipping point of a sustainable leadership revolution in corporations.

First, climate change presents humanity with a global challenge unlike anything we have ever faced before. Given its scope and systemic complexity, climate change will require actions from both the public and the private sectors, and from all of us – as consumers and producers, managers and workers alike. If COVID-19 served as a global stress test to gauge how prepared we are to deal with the kinds of challenges we will face because of climate change, we did not fare particularly well!

Second, governments are finally starting to act. Despite decades of neglect, timid aspirations are starting to be translated into more credible commitments. We already have the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals, providing specific targets for 2030. The European Union has been working on numerous initiatives, of which the Green Deal is just the latest. And if, as is promised by the incoming Biden Administration, the United States succeeds in rejoining the Paris Agreement, this would represent another boost to collective government action on sustainability.

Third, the financial sector – whose traditional emphasis on maximizing shareholder value has been one of the main reasons given by CEOs for why they can’t introduce more sustainable policies – is increasingly integrating environmental and social performance metrics in its processes. We are now more likely to see investors concerned about companies not doing enough on climate change, rather than about them doing too much.

So, we have an urgent existential threat, governments are mobilizing and investors are changing their tunes. Nothing to worry about then: Surely, the might, power and ingenuity of the private sector will solve things, just like in the 1980s with the Montreal Protocol. Remember that international treaty to phase out production of substances harmful to the ozone layer? Thanks to collective corporate action on that front, the world managed to eliminate ozone-depleting chemicals, helping the hole in the ozone layer to grow smaller.

Unfortunately, the kind of comprehensive decarbonization needed today is much more complex. It will require monumental capital reallocation and fundamental changes for entire industries, for corporate strategies and for business models. And although this transition will generate new jobs in some sectors and regions, it is also likely to cause job losses in others. To ensure a just transition, we will need to ensure that we have policies in place to help those who will suffer the most from the changes.

We are at the tipping point of a sustainable leadership revolution

The profound transformation we need corporations to make will also require a profound rethinking of corporate leadership. Sustainability cannot be bolted on to existing strategies but needs to be at their core. Corporate leaders, especially in large firms, need to accept their systemic role in society, assume responsibility for it, and act decisively to reduce their negative footprint while maximizing their positive impact in all areas:

- Strategically, they will need to explore novel business models, being mindful of how any changes they decide to make there may well endanger their own competitive position.

- Financially, they will need to shift investments away from legacy systems and technologies toward sustainable ones, in line with science-based decarbonization targets.

- In their marketing efforts, they will need to encourage more sustainable consumption and, in some cases, even discourage consumption – a marketing heresy.

- Operationally, they will need to rethink their entire supply chain.

- Organizationally, they should implement flexible ways of working that minimize employees’ carbon footprint.

- As leaders, they will need to inspire and energize the entire organization to embrace and internalize these novel goals, strategies and practices.

This radical rethink extends beyond the boundaries of the firm. Corporate leaders must exercise system leadership, engaging suppliers, consumers, NGOs, governments, scientists and other external stakeholders in novel collaborations. Rather than lobbying against stricter environmental regulation, sustainable leaders should be proactively designing regulation to create a global level playing field that limits arbitrage opportunism between countries, regions and jurisdictions.

Above all, sustainable leaders should not fall for simplistic ideas that have plagued much corporate sustainability discourse, that a win-win solution can always be found. Actually, a serious commitment to ambitious environmental and social goals will present trade-offs, and win-win solutions will not always be possible. Successful corporate strategies have never been easy to identify and execute, so we should not expect it to be any easier this time. There are no magic wands.

The world needs sustainable leaders not because the environmental and social challenges are easy to solve and obviously profitable, but precisely because they are wickedly difficult, and we need to reorient the creative power of business toward the development of solutions.

Sustainable leaders, it is time to act.

Fabrizio Ferraro is Professor of Strategic Management and Head of the Strategic Management Department at IESE.

This Report forms part of the magazine IESE Business School Insight #157. See the full Table of Contents.

This content is exclusively for individual use. If you wish to use any of this material for academic or teaching purposes, please go to IESE Publishing where you can obtain a special PDF version of this report.