Lessons from 9/11: Operations in times of crisis

01Lessons from 9/11: Operations in times of crisis

In 2021, on the 20th anniversary of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in the United States, it’s worth revisiting how leaders responded. That story contains useful lessons for distinguishing between clear, complicated, complex and chaotic situations, and managing the associated operations challenges accordingly.

By Federico Sabria, Alejandro Lago and Fred Krawchuk

On September 11, 2001, a few square blocks in Lower Manhattan were thrust onto the world stage when two hijacked planes struck the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center complex in New York City, claiming the lives of 2,753 people, in addition to 224 other people killed in plane crashes at the Pentagon and in Pennsylvania.

The operational response to this terrible attack was extremely challenging, to say the least. Some actions were highly appropriate, making them worth emulating; others are better left forgotten. This article highlights some key takeaways.

Having presented this material in various academic sessions at IESE, we know that many executives encounter challenges similar to those faced by New Yorkers that day, with clear parallels to the problems that they themselves have to manage when their business environments go from being simple and repetitive to complicated, complex and sometimes chaotic.

Simple wonders

Walking through Ground Zero today is a moving experience. It’s now the site of the National September 11 Memorial and Museum. Where the towers once stood are twin reflecting pools with waterfalls that disappear down two central voids. A tree that was pulled from the rubble – the Survivor Tree – was nurtured back to life and stands in the middle of a grove of memorial trees. There is an on-site train station, designed by the famous Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava and featuring a stunning Oculus roof. These are works of art that leave no viewer indifferent.

Despite everything, life goes on. Policemen make their rounds. Window washers work their squeegees. Baristas make coffee to go. And in the surrounding office towers, thousands of executives sit in front of their computers, going about the daily grind.

Most day-to-day processes are clear and simple

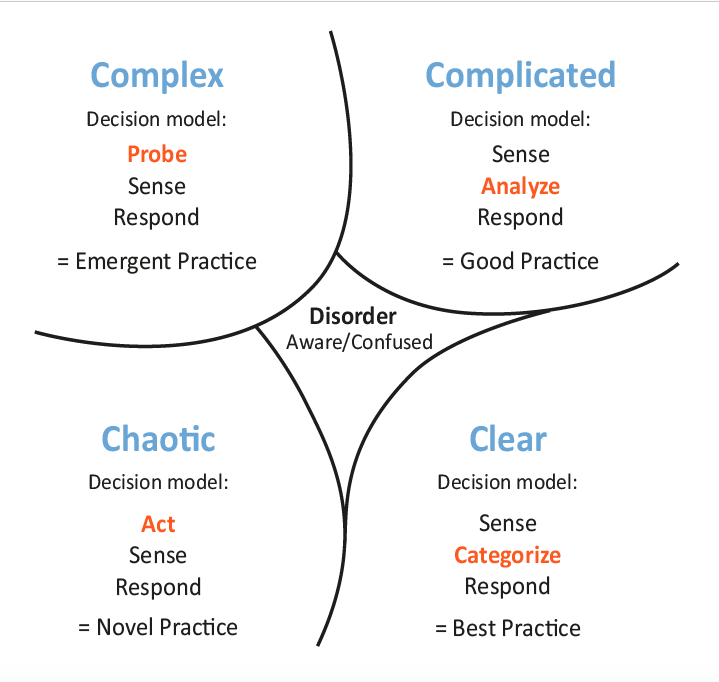

Life has returned to a state characterized by the Welsh management consultant Dave Snowden as clear and simple. See his Cynefin diagram, which we will refer back to throughout this article.

Anyone can understand cause-and-effect relationships. When these are clear, companies work hard to standardize them, so everyone knows exactly what to do and how to respond in any given situation. These are codified as best practices. In these contexts, we assess the situation (a dirty window, for example), we categorize the task (window cleaning) and we take action (we clean the window). So far, so simple.

Cynefin model

In this sense-making model called Cynefin (pronounced kuh-nev-in), we start in a central space of disorder – that is, not knowing what state you’re in. Snowden describes this space as “aware but confused.” First, decide the nature of the situation – ordered or disordered? – so you can get yourself out of that confused space. If ordered (right side), is it clear or complicated? If disordered (left side), is it complex or chaotic? Then you can start to manage it accordingly.

SOURCE: Go to Cognitive Edge: The Cynefin® Co. website (www.cognitive-edge.com) where you can find tools, resources and explainer videos to apply Dave Snowden’s model to your own operations.

When it gets complicated

However, “simple” does not describe the problem that the architect David Childs faced when designing One World Trade Center, the new tower he set out to build as a symbolic testament to American resilience after the attacks. It had to be taller than the previous Twin Towers. Indeed, when finally completed and officially opened in 2014, it became the tallest building in the United States, reaching a height of 1,776 feet (541 meters), a symbolic number because 1776 was the year the U.S. Declaration of Independence was signed.

Designing a tower that high requires techniques one can learn in any engineering or architecture school. The laws of physics apply, with known cause-and-effect relationships. Yet Snowden would say that Childs had a complicated problem on his hands. Few teams of professionals in the world would be able to handle challenges of that caliber. In designing and constructing a building like One World Trade Center, Childs had to search for innovative solutions based on deep, expert knowledge and analysis.

For example, the building had to be tough enough to survive anything, from the most violent storms or earthquakes to an attack like that of 9/11. That’s more complicated than erecting a steel frame on top of a concrete platform as was the go-to solution until 9/11. Instead, they invented a super-strength concrete core, like a huge tree trunk, to act as the spine of the building, which ought to withstand any impact. Also, when a building is that high, you have to solve the problem of how to deal with winds of 100-plus miles per hour pressing against the glass at the top. The solution was to change the building’s shape as it rises, so the air is deflected in different directions at every level, and the vortices can’t gain strength.

With complicated problems, there is no “best” solution but rather several good ones

Even the station designed by Calatrava was not so simple. The Oculus roof is more like a sculpture, and there were few steel suppliers able to execute it. The end result is magical, especially every September 11 when the sun is perfectly aligned with the central axis of the building and floods the central hall with light, shining most intensely at the exact hour when the second tower fell.

Were Childs’ solutions the best ones? Is Calatrava’s station the best designed ever? No. With complicated problems, there is no “best” solution but rather several good ones. And among the few experts able to address those problems, there’s no consensus on which is the “best” approach, because each has their own quirky way of doing things. But they all have one thing in common: They start, like with simple situations, by evaluating the problem. However, instead of putting it into a neat category like you would with simple processes, they analyze it. And only then do they go on to execute their solution.

Out of order

Whether simple or complicated, we’re still dealing with an ordered world where basic rules apply. Yet we know from experience that life can throw us into situations that are more complex or even chaotic, where obvious cause-and-effect relationships go out the window. That was what happened on September 11, 2001 and in the months afterward.

“As we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns, the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.”

These famous words were uttered in 2002 by George W. Bush’s Secretary of Defense, the recently deceased Donald Rumsfeld, in making the case for invading Iraq and toppling Saddam Hussein as a response to 9/11. Rumsfeld was asked by journalists whether there was definitive proof of weapons of mass destruction to justify such action. His answer made him sound like he was obfuscating.

But the known/unknown matrix is not a fudge. Variations of it are used to this day in project management and strategic planning, and it has some parallels with Snowden’s framework. The known knowns are the simple and clear world as described before, where everything is known and there are no surprises. The known unknowns – the things “we know we do not know” – are the complicated world for which the probability of future events occurring can be analyzed and determined.

Life can throw us into situations that are more complex or even chaotic

In the same way that Childs knew he had to solve design problems that he did not yet have answers to, many companies do not yet know how much they will sell next year, but sell they will. And just as Childs analyzed the numbers in wind tunnel simulations, companies use forecasting models and scenario analyses to make sales projections.

When an unknown challenge is presented to us for the first time, we try to understand its own internal logic and the cause-effect relationships governing it, so that we can transform the unknowns into knowns, or at least into known unknowns – the things “we know we do not know.” We’ll look at how to do that next in disordered environments.

Complex operations

In 2001, Mike Burton was in charge of the Department of Design and Construction, the agency responsible for most public buildings in New York City. When he got news of the attacks, he headed to Ground Zero. He was two blocks away when the first tower collapsed. By noon, he had begun to mobilize a team of engineers and contractors; by evening, they were walking the disaster site. Burton ended up managing the clean-up of Ground Zero, one of the most complex debris removal operations in history.

Unlike a normal debris removal project (that is to say, one that would be complicated), the buildings had collapsed like a house of cards in an uncontrolled way. In addition, the remains of nearly 3,000 people had to be recovered. Burton called on four construction companies he had worked with before and so had trusted relationships with them – a crucial factor for complex operations. A job of this magnitude meant only the best professionals in the country need apply. They divided the area into four quadrants and the teams met together at the end of each 12-hour shift to share what each was discovering and to decide what new action to take.

Having sensed the problem, engineers were able to secure the wall and avert another disaster

In complex situations, Snowden recommends proceeding through a process of trial-and-error – probing, making an assessment and, based on this, taking action. As each new action reveals its effectiveness, we adjust our way and new practices emerge.

On one occasion, a machine operator felt the ground vibrate and, raising the alarm, work stopped on the entire site. Later it was found that a retaining wall of the Hudson River was about to give way and flood all of Ground Zero and much of the city’s subway. Having sensed the problem, engineers were able to secure the wall and avert another disaster.

In a custom program we carried out on IESE’s New York campus, we had the privilege of being able to invite Lou Mendes, Mike Burton’s right-hand man during that incredible project. He helped us understand that in this type of complex project, there is no master plan. There’s an objective, and within that, each and every one of the participants must improvise, adapting their response to achieve the goal at all costs. As our dear, late colleague, Josep Riverola, would say, “Don’t bring me problems, bring me solutions.”

By May 2002, the job was finished – under budget, ahead of schedule and, most important, with no lives lost. What can we learn from Burton for managing complex projects? Professional teams (never tackle a complex project with newbies); relationships based on trust; the use of prototypes to probe the reaction of the system; clear objectives, with continuous evaluation and the ability to pivot: These are the ingredients for success in a complex world.

Managing chaos

Unfortunately, none of the rules applied on September 11, 2001. Dr. Antonio Dajer will never forget that day. He was the only emergency physician on duty at the hospital closest to the World Trade Center. Because the World Trade Center had been attacked once before, in 1993, when terrorists detonated a bomb in an underground garage, New York City had developed contingency plans in the event of a future attack – although Dajer’s smaller community hospital was envisaged as playing a backup role, supporting the larger hospitals, not being in the eye of the storm.

Still, the previous years’ disaster drills enabled the hospital to spring into action. Within minutes of the towers being hit, they sounded Code Yellow. Dajer suspended all scheduled operations and began freeing up beds. A surgeon who started his day thinking he was going to perform cosmetic surgery instead found himself assisting in ER. The cafeteria was converted into a field hospital like in a war zone.

While you cannot exactly plan for chaos, you can at least prepare

This highlights that, even in the midst of chaos, there are still some available practices to draw upon. While you cannot exactly plan for chaos, you can at least prepare. So, even though New York’s most radical disaster plan had never envisaged a scenario like 9/11, those doctors were still able to pivot in an emergency.

In these situations, there is no time to test or analyze. You have to act first, and after doing so, decide whether to change course. You have to keep moving, and move quickly. In doing so, you are beginning to place constraints on the chaos.

Although you must rely heavily on team knowledge and mutual support, decisions cannot be made collegially, because there’s no time for it. The person in charge must step up and decide. Two situations exemplify this.

When the first tower collapsed, a massive dust cloud rolled toward the hospital. Dajer quickly ordered the doors shut before the entire hospital was engulfed and contaminated with dust. But then he saw the hands pressing against the glass outside, imploring to be let in, and he realized he had to open the doors and look for another quick solution to keep the operating rooms sterile.

In another instance, the mayor of New York went to survey the damage at the World Trade Center. When he arrived at the scene, he asked the fire chief if it were possible to get rescuers up to the top of the tower to help people who were trapped up there, and the fire chief said no, he could never put one of his men above the fire.

Although many rules may have to be violated, there need to be a few that cannot be broken

This encapsulates another important lesson for chaotic situations: Although many rules commonly used to control operations may have to be violated, there still need to be a few ground rules that cannot be broken. Even in the worst case scenario, there must be some red lines that cannot be crossed; it cannot be “anything goes.” Discerning which rules can and should be broken and which ones cannot and should not is the hallmark of leadership.

In the final analysis, New York City gave the world a great lesson in how to react to a catastrophe of unimaginable proportions. They demonstrated how professionalism and a sense of duty and sacrifice enabled them to manage that fateful day, to save lives and, later, to transform Ground Zero into what it is today: a symbol of resilience that represents the best of this vibrant city.

As Dr. Dajer later recalled: “I think my big takeaway from 9/11 is that if you give trained (professionals) clear direction and adequate resources, they will self-organize and do a very impressive job. Everyone remembers the feeling in New York City that day. There was so much solidarity throughout the city and the country. We were so together. And there was a tenderness there – a compassion that we felt for each other that I would like the world to have. It just goes to show what people really can do when they rise to the occasion.”

Check your readiness for disaster

Given the COVID-19 pandemic, sociopolitical upheavals, technological disruptions and other ongoing VUCA challenges happening around the globe, we think 9/11 and Snowden’s Cynefin framework provide many practical and necessary lessons that business leaders could apply today. Ask yourself:

What are the clear, complicated, complex and chaotic situations your organization currently faces? Do you have the right teams in place, with the right mindsets and skillsets, to handle these extraordinary situations?

How well do you sense the environment? What’s the status of your organization’s “human sensor network” that pays attention to, and reports, weak signals? Sensing the environment is key to anticipating the kinds of problems (complex, complicated, clear and/or chaotic) you might be facing. Whether 9/11 or COVID-19, history proves the signs are there – if you are paying attention.

How are you checking assumptions, biases and blind spots? We all tend to see things our own way. Engineers may pick up on linear patterns and cause-and-effect relationships, while designers may see non-linear aspects and interdependent systems. Organizations need both perspectives. How many different voices are represented around your table? What can you do to amplify and sharpen the lenses by which you view the world?

How are your information flows? 9/11 illustrated the tragic consequences of what can happen when different departments do not share critical pieces of information that would have saved lives and benefited the whole organization. Flat and connected communication systems are key to help ensure decision-makers at all levels have access to information and are empowered to act on critical signals.

How responsive and adaptive are your organizational processes? Especially in dynamic environments, managers need to have nimble processes in place to regularly assess what’s working, what the organization is learning and what needs to improve. Chaotic and complex challenges are constantly evolving, so leaders need to be continuously monitoring the impact of their decisions and stress-testing their strategies by considering best- and worst-case scenarios, seeking alternatives, allowing contingencies, and iterating in light of changing circumstances.

Finally: What might you do better or differently to best align your challenges with appropriate responses?

The authors

Federico Sabria

Professor of Production, Technology & Operations Management at IESE and a consultant in the field of logistics. A Fulbright Scholar, he holds a PhD in engineering from the University of California, Berkeley.

Alejandro Lago

Professor and head of the Production, Technology & Operations Management Department at IESE. He holds a PhD in engineering from the University of California, Berkeley, where he was a Gordon F. Newell Fellow.

Fred Krawchuk

Senior lecturer of Production, Technology and Operations Management at IESE, as well as an executive coach, writer and CEO of the Pathfinder Consulting Group. A graduate of West Point, IESE and the Harvard Kennedy School, he is a decorated veteran U.S. Army Special Forces Colonel, having led high-risk operations around the globe, from the Balkans to Iraq and Afghanistan.

SOURCE: This article is based on Executive Education sessions delivered by the authors on this topic, as well as a special talk delivered by Prof. Federico Sabria at the National September 11 Memorial and Museum in New York City on October 11, 2018, as part of IESE’s Global Alumni Reunion.

This article forms part of the magazine IESE Business School Insight #159. See the full Table of Contents.

This content is exclusively for individual use. If you wish to use any of this material for academic or teaching purposes, please go to IESE Publishing where you can obtain a special PDF version of this article as well as the full magazine in which it appears.