Philanthropy: Giving back by giving away

01Philanthropy: Giving back by giving away

Making a difference and giving back to society have never been more urgent. Here’s how business leaders and companies are lending a hand – and it’s not only money that matters.

The coronavirus pandemic may have locked us down but it unlocked something else: philanthropy. Derived from the Greek words phil (love) and anthropos (mankind), philanthropy literally means “love of humanity,” and the pandemic has inspired an outpouring of that, from big and small donors alike, all wanting to play their part in the wider humanitarian effort.

For example, several businesspeople from IESE’s Executive MBA Class of 2014 got together and set up a pro bono consultancy called SOS4pymes, which, as its name suggests, provides lifesaving help for small businesses (pymes or SMEs in English) which have borne the brunt of the lockdowns. In Spain, as in many other countries, small businesses – from the local butcher and greengrocer to gyms and mom-and-pop stores – generate 50% of total employment, and the country’s economic recovery depends on their survival. At www.sos4pymes.com small businesses can register their need and get professional advice from more than 100 collaborators: lawyers, financiers, engineers, managers of multinationals and IBEX 35 companies, experts in operations, online marketing and trade. The goal, according to the founders, is to “help those who help our societies flourish,” based on three non-negotiables: (1) that the help is personalized; (2) that it is effective, making a real, tangible, demonstrable impact; and (3) that it is totally selfless and free, so no one is trying to make money out of it.

This latter point is key. It’s reminiscent of Didier Pittet and William Griffiths, the inventors of the hand sanitizer we use daily, who decided to give the formula away as a pure act of philanthropy. “We have not worked for companies or for money,” they said. “We have done something tremendous for humanity.”

Many such selfless acts by members of the IESE alumni community were collected and shared here: www.iese.edu/community-covid19. Juan Carlos Garavito (GEMBA ’20), CEO of the intellectual property firm Clarke Modet, offered his professional services to organizations who could use smart tech to mitigate the effects of COVID-19, and he raised money for food banks. Other Executive MBA alumni, like Jaime Barreiro, Julia Zhou and Ge Wang, purchased masks and other personal protective equipment (PPE) for healthcare workers and donated them to hospitals everywhere from Spain to Italy. “Love knows no borders,” said Wang (www.iese.edu/stories/united-in-action). Arancha Caballero (PDG ’18) distributed tablets to hospital patients so they could safely communicate with distanced loved ones. And the list goes on.

More companies and charities are working hand in hand to help solve the world’s problems

Motivated individuals can make a difference. And you don’t need the bank account of Bill Gates to do it – though that helps, too. More and more companies and startups are working hand in hand with charities and NGOs to bring their resources and expertise to bear on helping to solve the world’s social problems.

To make our giving more meaningful, let’s take a step back to look at the nature of philanthropy and the many different forms it can take.

A brief history

Individuals or organizations face the same fundamental question: What to do with their wealth? In his book Why Philanthropy Matters, Zoltan Acs suggests three basic answers: keep it, tax it or give it away.

In collectivist societies with strong welfare states (like in Europe), the answer is usually to tax it, as it is generally regarded as the government’s job to address social needs and promote the common good. In individualist societies with less government intervention (like in the United States), people prefer that the money stays in their own pockets and they can give some away if they so choose; tax breaks may be used to incentivize giving (see below). This encourages different philanthropic cultures.

The role of taxes

In some countries, like the U.S. and Spain, taxpayers can claim a deduction for charitable giving on their tax returns and get a rebate on their donations. In other countries, like the U.K., it’s the charities themselves that can claim the rebate from your donation. Research on these two different systems shows that people tend to give more under the second system where the charity receives the tax benefit.

However, although the personal income tax deduction may not be people’s main motivator for giving, other research shows that if that deduction were reduced, eliminated or capped, people’s giving intentions would go down. There’s even research indicating that taxing wealthier people at higher rates would incentivize more charitable giving, because they could then claim bigger personal deductions. In one U.S. study, 74% of high net worth philanthropic givers opposed imposing caps on charitable deductions.

In another study, participants were given the option of giving part of their earnings to a charity of their choice, or giving it to a third party who would keep some it before disbursing the remainder to charity (to replicate the role of paying tax to the government). Few liked the second option – though if it were made clear that the third party (aka the government) were using the money responsibly, participants were more relaxed. An experiment involving MRI scans even showed the same reward centers in the brain were stimulated whether people were allowed to give $100 to a local food bank or the same money was taken from them and given to the same cause. The key is in seeing your tax dollars being put to good use.

SOURCE: “The surprising relationship between taxes and charitable giving” by Andrew Blackman in The Wall Street Journal.

In the United States, this gave rise to the modern figure of the business philanthropist, epitomized by John D. Rockefeller, the 19th century oil tycoon who used his vast fortune to fund all kinds of public goods that would normally be served by governments: education, medicine, scientific research and the like. Subsequent generations have continued that legacy, with his grandson, the late David Rockefeller, becoming one of the first signatories of the Giving Pledge – the campaign launched by Bill and Melinda Gates and Warren Buffett in 2010 to get the world’s ultra-rich to give away their wealth to philanthropic causes. For their part, the Gates joined with the World Health Organization, UNICEF and the World Bank to set up Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, to make sure that no child got left behind with immunizations.

This is an example of how philanthropy plays out particularly in the United States, where it is seen as “an essential ingredient of American capitalism… woven into the entrepreneurial spirit of America,” writes Acs. Through philanthropy, the wealth created by the capitalist system is then reinvested in projects that generate positive externalities for society.

But this is only one part of the philanthropy story. Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, another phenomenon emerged: corporate social responsibility. This involves companies donating to charities or supporting causes favored by employees or customers in order to be seen as good citizens.

Some dismiss this as PR. They stick with Milton Friedman’s argument that the only social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. Philanthropy, if pursued by a company at all, exists at the peak of a Maslow-like “pyramid of responsibilities,” to be pursued only after basic economic needs are met.

Harvard’s Michael E. Porter says corporate philanthropy can work if it is shifted “into strategic giving: philanthropy focused on enhancing competitive context.” For Porter, corporate philanthropy is most beneficial when there is a convergence of social and business interests. He ties it back to his Four Elements of Competitive Context, treating philanthropy as “investments” or resources to leverage in order to improve the company’s competitive context. So, on that basis, contributing to a university or a job training program could be justified because it develops a local base of talent that the company needs.

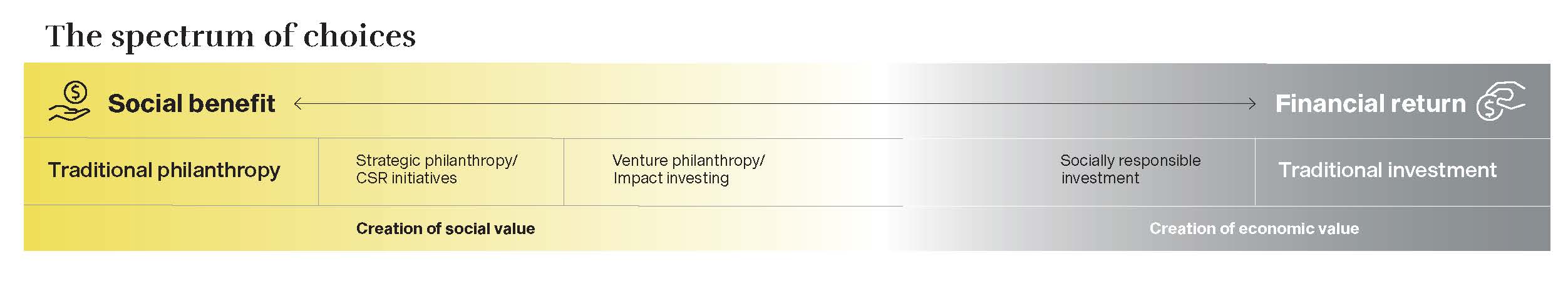

In recent decades, we have also witnessed the growth of venture philanthropy, impact investing and various other related forms of socially responsible financing, where investors channel their money toward social enterprises to generate some net positive impact for society. Like Porter’s strategically minded view, this type of philanthropy prioritizes measurable, sustainable impacts according to clearly defined objectives for social and financial returns. While inviting in the private sector does expand the capacity of the public sector to tackle social problems that it can’t solve on its own, it does take philanthropy a bit further away from its roots.

The spectrum of choices

SOURCE: Based on La apuesta del impact investing. Invertir contribuyendo a la mejora de la sociedad (Betting on impact investing: investing to contribute to the betterment of society). A special report (ST-380) of the IESE Center for Business in Society and DiverInvest.

Not everything is money

Each of these expressions of philanthropy has their pros. However, it must be stressed that true philanthropy does not always have an economic logic. “The danger of framing philanthropy in economic terms is that you may lose sight of the selfless character of philanthropy – that is, giving something without expecting to get anything in return,” says IESE professor Joan Fontrodona, holder of the CaixaBank Chair of Sustainability and Social Impact. Certainly, using resources intelligently and efficiently to maximize their impact is desirable, but “we cannot ignore people and groups in society who do not represent any opportunity for shared value creation.”

IESE’s Antonio Argandoña agrees: “One of the core features of philanthropy is its universality – that all people be treated equally. Introducing a criterion of instrumental rationality into philanthropy may lead us to direct funds exclusively to those who yield the best results.”

This is not to say your philanthropic efforts should be haphazard. In looking at the spectrum of choices, it’s not either/or but both/and. Judge the philanthropic cause on its merits first, before doing any cost/benefit analysis. As Argandoña puts it, keep your eyes foremost on “compassion for the one who suffers” as you seek the most effective way to help.

Banking on saving lives

To firewall the commercial from the charitable side, some companies maintain a separate charitable foundation. This gives the company more freedom to act in the social realm, engaging in valid and important work through its foundation that it couldn’t so easily justify through its day-to-day running of the business. In some cases, the foundation enhances the business activity, creating new synergies.

In Spain, ”La Caixa” Foundation – part of CriteriaCaixa, the investment holding company that manages the group assets, including CaixaBank – began collaborating with Gavi in 2008 because, as its director of International Programs, Ariadna Bardolet (PDD ’17), explains, “All efforts are needed to continue supporting vaccination programs, especially in the poorest countries.”

Gavi is included in CaixaBank’s portfolio of products, giving all employees and banking clients – businesses and individuals alike – the chance to donate to the cause. ”La Caixa” Foundation matches the donations that CaixaBank receives by up to 2 million euros, with the Gates Foundation agreeing to match that new amount again, meaning that every euro donated via CaixaBank ends up being worth four times as much.

CaixaBank keeps the focus on the cause, which for the past six years has been on vaccinating children in Mozambique. When banking managers meet with their clients, they assess which ones seem to have the necessary empathy and sensitivity before mentioning the initiative to them, to make sure they have genuinely committed partners. Involving those who strongly identify with the cause is one of the keys for lasting success. (See more below.)

5 keys for sustainable philanthropy by companies

At a time when the world is striving to find solutions to global problems that are too complex to be tackled individually, business and charity working in partnership may hold the key. Indeed, private organizations joining forces with others from civil society, even those quite different from each other but with a shared vision to put people at the center, is the basis of U.N. Sustainable Development Goal 17.

Here are five takeaways from the ”La Caixa” experience to guide your company’s own philanthropic endeavors.

1. Set a focused, concrete target

Concrete targets are easier to quantify, and visible results generate a sense of belonging and identification with the cause.

2. Report results in detail

Reporting donations in detail and internally auditing the program not only ensures that the money collected is being used efficiently, it also provides transparency and builds trust, which strengthens relationships with donors.

3. Treat donations on the same level as products

Make it clear that the organization considers donations as important as any commercial product the company offers. When collaborators and customers know that their donations are as important as sales for the organization, commitment is boosted and links between stakeholders are reinforced.

4. Use non-monetary incentives

Offer experiences to employees, such as visiting the project or volunteering, if allowed. Recognize employees who stand out, such as those who collect the most donations. This creates more identification with the cause. And a committed employee can become a champion within the company.

5. Set an example and communicate effectively

Be the first to step up and then ask others to join you. Strategically communicate the work you are doing, but keep the spotlight on the cause, not on yourself. Reputational benefits come from others seeing the good work you are doing and then judging it as so for themselves, not from you bragging about it. Let the work speak for itself.

READ ALSO: 5 strategies to build an alliance for social good

See the above presented in video format below.

SOURCE: “Gavi-’La Caixa’: A successful alliance to promote childhood vaccinations” by Diego Arias Padilla and Joan Fontrodona (2020).

”La Caixa” Foundation raises funds through employees, customers and allied companies to support Gavi programs to vaccinate children in Africa

For Bardolet, a banking group lending support to what she describes as “an initiative to save lives” makes sense. “The private sector holds great potential as well as great responsibility in the fight against inequality. A social commitment and business success are increasingly viewed as mutually reinforcing.”

This is the idea behind Gavi’s creation of COVAX, to get private sector philanthropy to join with governments, global health organizations and others in civil society, to ensure equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines for people around the world, especially in less wealthy countries.

To this end, another banking group, Citi, created a $500m vaccine bond for the International Finance Facility for Immunization Company (IFFIm), with proceeds going to Gavi. This social bond continues to be oversubscribed, with IFFIm attributing the strong demand to the clarity and focus of the cause – another key for success.

“We are proud to have been selected to advise and assist Gavi in finding risk mitigation and execution strategies in connection with the COVAX Facility, including supporting the building of strategies to operationalize and maintain the Facility,” says Paco Ybarra (MBA ’87), CEO of Institutional Clients Group at Citi. “This is part of Citi’s ongoing commitment to combat this pandemic and a clear demonstration of who we are as a firm.”

Multiple benefits

Apart from the good that philanthropy brings for the beneficiaries of companies’ or individuals’ giving, it also brings benefits for the giver. These may be tangible: financial returns, in the case of those who opt for venture philanthropy; or competitive advantage, for those who make strategic choices regarding which philanthropic projects they will support. But there are also intangible benefits. And perhaps nothing demonstrates this more than when family businesses take up philanthropy, often through family-run foundations.

IESE’s Josep Tapies, who has done extensive research on family firms and what makes them tick, finds that philanthropy serves to express what the family, and by extension the business, really stands for. It serves to bind everyone together, based on shared values, helping to ensure the survival of the business over time. Younger generations, in particular, are often driven less by profit motives than they are by giving back and making a difference. Giving them the opportunity to do something that will make them feel proud that they are working not just for the well-being and prosperity of their own family but also for the well-being and prosperity of the community in which they operate is a powerful, unifying force. It strengthens everyone’s long-term commitment – something that interests any business concerned about its sustainability, and even more so a multigenerational family firm.

Tapies writes: “Although there may be no direct economic return, those who engage in philanthropy gain numerous benefits: cohesion, unity, commitment, well-being, harmony. Most important, philanthropic activities allow family business owners to keep the family legacy alive, generation after generation. What more could you want?”

This applies to non-family firms, too. Research indicates that one of the best ways of sustaining philanthropy over time is if the participating employees’ volunteering becomes an integral part of who they are and how they identify themselves. As corporate volunteering programs are growing (one study found the percentage of top multinationals offering them nearly doubled between 2010 and 2017), it is good to know which factors foster engagement, so that corporate philanthropy doesn’t end up as a short-lived, one-off gesture.

As mentioned earlier, there needs to be an enthused, committed employee who acts as the project ambassador, encouraging others to join and keeping the momentum going.

There needs to be an enthused, committed employee who acts as the project ambassador to keep the momentum going

Consistency with an organization’s values and culture is also key. “The systems for managing people, from compensation policies to job designs, as well as the work environment and culture must work together harmoniously,” IESE’s Jose Ramon Pin noted in the report CSR: consistency is credibility. “Underpaying employees, or a huge gap between the highest-paid and lowest-paid workers, or not complying with basic health-and-safety standards: these sorts of things make it inconsistent to talk about solidarity with third parties while not practicing it within the workplace. Everything needs to be coherent with the organization’s overall governance and design.”

This echoes well-known research by Wharton’s Adam Grant. Deficits in what he calls “value concordance” may lead employees to look for fulfillment elsewhere if they derive no meaning, recognition or support from their day jobs. Anne-Claire Pache, Chaired Professor in Philanthropy at ESSEC, takes it further. She finds that, when it comes to keeping corporate volunteers engaged, also letting employees choose what cause(s) they want to support may count for even more than managerial recognition and support. In fact, this self-determination piece may be a mediating factor in “driving employees’ lasting commitment, thereby unleashing the potential positive impact on employees, companies and beneficiaries alike.”

Every little helps

Putting more “giving power” into the hands of the individual has never been easier, thanks to technology, which has democratized giving so it is not just giant corporations and the ultra-rich who can afford to be philanthropic.

Trends

SOURCE: Trends in Philanthropy for 2021 by the Johnson Center for Philanthropy.

“Decolonizing” wealth

Handing over more control, so recipients become partners and have more of a say over how funds are used.

Horizontal philanthropy

Rather than the top-down model of international development assistance, communities are mobilizing their own resources and engaging with each other to address shared challenges arising from members of their own community, more in keeping with the tradition of mutual self-help, as is found in Africa.

Celebrity-led activism

Athletes and artists from around the world are funding causes that are increasingly political in nature. For example, the Korean “K-pop” boy band BTS mobilized its global fanbase to match its own pledge to fund social activism in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. This youth-led philanthropy is designed to amplify community voices and change public policies.

Throughout 2020, individual household giving to charity and volunteering were up, especially for food banks and healthcare-related causes, according to the Association of Fundraising Professionals (AFP), which administers the largest database on charitable donations in North America. “What we’re seeing is that people remain very generous and continue to support their neighbors, communities and charitable causes when they face crises and hard times,” said a spokesman for the AFP’s Fundraising Effectiveness Project. “The exciting part is the increase in small gifts” from unexpected donors – that is, average people suffering from the pandemic themselves.

This is even more extraordinary when you consider that the largest living adult generation who comprise most of today’s workforce (millennials) own just 4.6% of the total wealth, while 70% of all wealth is concentrated in the pockets of those in their late 50s and older, and who are approaching or who are already in retirement (the so-called boomers and silent generation). (Although these stats are from the U.S., the same is broadly true in other Western nations.) Those who have less seem to be giving more.

The dilemma of billionaire philanthropy

“For the one who has been given much, much will be required.” According to this saying, we should expect more philanthropy from wealthier individuals. Yet relying on philanthropy from the top 1% of society would seem to underscore the very social inequality that such philanthropy is supposedly aiming to solve.

The Dutch historian Rutger Bregman famously shook up Davos in 2019 when he said: “Just stop talking about philanthropy and start talking about taxes!” In other words, is it right for billionaires to exploit tax loopholes and tax havens, depriving governments of the funds they need to provide for all their citizens? Some critics argue that all the money spent on philanthropy amounts to less than if those billionaires had just paid more taxes to begin with. Plus, the money would have been spread around to address wider social needs, not directed at one person’s special interest.

Disney heir Abigail Disney, herself a philanthropist, is the first to call out the unfairness. “Philanthropy is often offered as the answer to the problem of inequality,” she testified before a U.S. congressional committee on the subject in 2019. “While wonderful, philanthropy is not the answer … Philanthropy offers a man a fish, even teaches a man to fish, but persistently fails to ask why the lake is running out of water.”

She believed the economic structures – “the very structures, in fact, that make philanthropy possible” – were deeply unfair and needed to be reformed. “It is time to bring a moral and ethical framework back to the way we discuss business … for business leaders to recognize that they have altered the nature of this communal project.”

The growing backlash against rich elites demands a deep reflection on what kind of philanthropy is legitimate today. A Recode article laid out the challenge this way: We may not like “the powerful exerting their power … but is that more concerning than the people who might die if (billionaire philanthropists) didn’t make mega donations?” Yet even if the philanthropic gifts are welcome, “we still have to continue to ask questions about how we grew so dependent on them in the first place.”

Here is where platform-, social media- and SMS-based methods of direct giving come into their own. It’s “the long tail” of giving, where micro donations can be aggregated to make as big an impact as the one-time mega gift of the traditional wealthy donor.

GiveDirectly, a charity that makes direct cash transfers to needy individuals in the U.S. and Africa, was quoted as saying: “You’re seeing people giving out cash themselves on Twitter. I haven’t seen a period like this where so many people from so many different types of philanthropy have started with cash transfers as a primary tool in their toolbox.”

The Spanish foundation Migranodearena (which translates as “My grain of sand”) perfectly expresses this new reality. It’s a crowdfunding platform that enables individuals, as well as companies, to start their own crowdfunding campaign for a social project, either their own or someone else’s. Over 4,000 NGOs raise funds for their projects through the platform. In 2020 the platform raised a record 4 million euros, of which half went to causes related to COVID-19.

As creator of Migranodearena and founder and CEO of DiverInvest – an independent financial adviser for clients who may want to engage in impact investing or venture philanthropy – David Levy has seen all sides of giving. From his point of view, the philanthropic spirit unleashed by the crisis is not a temporary blip. “This catastrophe, which affects everyone equally, has allowed us to witness the creation of a new situation in which solidarity is multiplied.” He is optimistic that, even after the pandemic fades, philanthropy is here to stay.

Even after the pandemic fades, philanthropy is here to stay

IESE’s Fontrodona agrees: “A sense of solidarity has been awakened. We are in an extraordinary situation that has generated extraordinary behaviors. Companies have pulled out all the stops to alleviate the effects of the crisis, even temporarily setting aside their own businesses to help out” (as we saw when manufacturers switched their normal production to make face masks, hand sanitizer or ventilators, for no personal gain). “Having done such things, I believe companies and individuals will have gotten a taste for it and want to do more. And hopefully we can expect to see greater institutional support in favor of such initiatives.”

Santiago Ruiz de Velasco, one of the collaborators with SOS4pymes, sums it up this way: “Society is facing an unprecedented situation where everything is new, everything is uncertain, and there is no script. It is in these moments that we are put to the test. The health services have been proving for months that they are up to the task. Now it is our turn, that we, from positions of certain privilege and comfort, can help those who have helped us to be who and where we are today. We cannot fail them. Our help is not charity, it is simply justice.”

READ MORE: Filantropía y RSC (Philanthropy and CSR). A special report (ST-487) of the CaixaBank Chair of Sustainability and Social Impact (formerly the CaixaBank Chair of Corporate Social Responsibility).

“Gavi-’La Caixa’: A successful alliance to promote childhood vaccinations” by Diego Arias Padilla and Joan Fontrodona (2020).

Josep Carreras: “Listen to that inner voice”

02Philanthropy: Giving back by giving away

After a musical career spanning 50 years, Josep Carreras’s philanthropy through his leukemia foundation remains his other life work.

Josep Carreras, the renowned tenor, is the perfect example of “giving back.” In 1987, at the age of 40, he was in Paris recording a movie version of Puccini’s La Boheme, one of the productions for which he was famous. Feeling ill, he went for a checkup and was diagnosed with leukemia. He spent the next year in hospitals and considers himself lucky to have survived. A year later, he established the Josep Carreras Leukemia Foundation, whose ambitious mission is “to make leukemia a 100% curable disease for everyone and in every case.”

“When I got sick, so many people turned to help me, and I wanted, somehow, to return all these signs of affection, both to society and to the scientific community,” he said in a 2013 interview. “The idea of this project came about by sheer gratitude to society.”

Following his recovery, he held a benefit concert at an appropriate location – the Arch of Triumph – in his home city of Barcelona. But it was his comeback concert staged with fellow tenors Luciano Pavarotti and Placido Domingo at the 1990 FIFA World Cup Final in Rome that launched the global sensation known as the Three Tenors, leading to a long-running series of benefit concerts around the world. In addition, Carreras has given hundreds of charity concerts and recitals specifically to raise funds for his foundation and its affiliates in the United States, Switzerland and Germany.

Here, he explains the importance of philanthropy and why the values that underpin it – rigor, professionalism, transparency and a warm, humane attitude – are even more important when your own name is attached to it.

In getting people involved in philanthropy, what is the role of empathy?

Everything starts from there. For me, the personal experience of having leukemia was what made me want to help others in the same situation. If you are able to relate to those who are suffering from a serious illness or going through hard times, it strengthens your own resolve to fight and makes your own involvement genuine. Empathy is essential to build the most important thing in a leader: credibility.

Only then are you able to form a good team who can transmit that same empathy to society, by enlisting the help of the scientific community and other patients in well-managed awareness-raising activities. It is crucial that you devote time and attention to your collaborators in the cause, making them feel that their contribution is valuable, giving them credit, and sincerely conveying that you appreciate their dedication and commitment.

Has the shared experience of the pandemic made people more empathetic and predisposed toward philanthropy?

I can only speak for our foundation and partners, but we have been impressed by the faithfulness we have seen throughout the pandemic. For example, we launched a special appeal to investigate aspects of oncohematology in relation to COVID-19, and the response was very generous: We raised more than 600,000 euros in just a few weeks. Our foundation counts on the support of over 100,000 members, and in 2020, despite the pandemic and the poor economic prospects for many families, we lost hardly any supporters. I am extremely grateful for that.

Moreover, seeing the scientific community coming together and producing effective vaccines in such a short period of time is exciting and shows that people can move quickly if the will is there and they are given the necessary resources.

How do you keep people engaged?

Through constant awareness-raising – generating and disseminating good information that motivates, excites and sensitizes people about the disease, the patients and their experience, and also about the enthusiasm, genius and dedication of the health professionals and researchers who are working to find a cure.

“People to whom society has given much have an even greater obligation to give back”

It’s vital to keep doing this, day after day, year after year, so the philanthropy is sustainable and not just a one-off activity when there is a crisis. At any rate, in our field, the emergency is permanent. We still lose too many children and adults to leukemia. Advances have been made but there is still a long way to go.

How do you involve companies in philanthropy?

We try to get companies and their employees to be linked to projects in the most direct way possible, so they know the objectives of our research and the people who develop it. We want people to get involved more personally, not just make a blind donation.

Crowdfunding platforms such as Migranodearena.org enable companies as well as individuals to set up their own solidarity projects. Many of these are very personal initiatives, raising funds for our foundation in memory of a loved one or in solidarity with a patient or leukemia survivor. Through this one platform alone, we have collected around 330,000 euros via 7,900 donations, which averages out to 42 euros each. This shows how modest donations from motivated individuals doing a sponsored run or bike ride can add up to make a big impact. The personal engagement is key.

Does involving companies add complications for non-profits?

We must be careful, as the regulatory and social demands for accountability are growing. But that is a positive thing: It encourages us to be more rigorous, more transparent in sharing the objectives and methods used to achieve them, and more focused on delivering results.

You could say that engaging in philanthropy adds more complications for companies than it does for us. Increasingly, companies have to complement their financial statements with reports on their results in terms of reputation, environmental impact, contribution to the community and the development of their employees. NGOs have always had to manage those many variables in addition to the economic one, especially with regard to reputation.

Is this a new development for some companies?

Without a doubt. Companies no longer only contribute to society by creating wealth and employment; they are expected to be exemplary in all dimensions, from the way they treat their people to the environment. Consumers want to deal with good organizations that behave with rigor and transparency. In this regard, philanthropy can add legitimacy to a company’s activities.

The other side of this is that there is a recognition that the State alone cannot meet all social needs nor contribute all that it should to scientific research. Accepting that there may be a place for private-sector philanthropy is a sign of a mature society.

What about the place of celebrity philanthropy? Does being famous help or distract from the cause?

Fame often comes before a well-known person is fully committed to a cause. There will be those who practice philanthropy to artificially prop up their fame, but I am convinced that is the exception. Most famous people who stand in solidarity with a cause do so from the heart. They don’t need the additional fame that might come through philanthropy.

For me, fame is something that has been conferred on me by society. And having been shown appreciation by society and enjoyed a certain degree of prosperity, then I see it as a great opportunity to use my position to return my appreciation through philanthropy for how much I have received. People to whom society has given much have an even greater obligation to give back what has been so generously bestowed on them.

What advice would you give to others to use their position of privilege constructively?

First, don’t trust the flatterers. Surround yourself with a good team. And, above all, listen to that inner voice, dedicating yourself to what you believe will help others live better, breathe easier, and spread more peace in the world.

Catalina Parra: “I want to change the world”

03Philanthropy: Giving back by giving away

Catalina Parra Baño is the founder of the foundation Hazloposible, chair of the impact investor Chandra3X, and a board member of the Centre for European Volunteering. She also co-founded UEIA (pronounced like ‘huella’, the Spanish word for footprints, as in the mark you make), which was the first business accelerator for social entrepreneurship in Spain. In 2019, she was awarded Social Entrepreneur of the Year by Ernst & Young.

For Catalina Parra, charity begins at home. Growing up, the door was always open, and her parents inculcated in her a strong sense of helping others in need. She started volunteering in her teens, helping out at an orphanage in Morocco when she was 16. After earning an engineering degree from Comillas Pontifical University in 1993, followed by an MBA at IESE in 1996, she started her career as a consultant, rising to partner, until a trip to India in 2001 changed her path. “When you work in consulting, you live in a kind of gilded cage: They pay you very well, the work is interesting, you travel. But four months in India made me reflect on what was really important. What would I want people to say at my funeral: that I was a fantastic consultant or that I was a person who tried to change the world?” She chose the latter, as she explains in this interview.

How did Hazloposible (which means “Make it possible”) get started?

It started from a common experience: An NGO would need donations or volunteers but not know where to find them. Or a company might want to participate in some charitable work, or volunteers might be looking for opportunities to collaborate according to their interests and availability, but not know where to find them. And so people would just ask around informally, “Hey, do you know anyone who does this or where I can find that?”

I said to myself, “Why don’t we bring these two sides together? Let’s be the bridge, the catalyst.” We saw the capacity to generate value if we could get citizens to collaborate with NGOs, and NGOs to collaborate with companies, and close that circle. It’s better for everyone, and no time is wasted.

When we started over 20 years ago, we held physical meetings. We would literally get the interested parties together in a room – three companies and three NGOs, for example – and we would seat them at different tables arranged by theme – pollution, youth, unemployment, abused women – and then they would work out their collaboration from there.

How has technology helped?

Technology has opened possibilities for collaboration as well as for training. When we started, we wanted to take advantage of the internet for collaboration and networking, because connecting volunteers is so important. We could see technology bringing enormous value to the for-profit sector, and we thought, why not for the non-profit sector, too? I launched my first crowdfunding portal about 15 years ago, when such things were still little known. This was before Facebook, and we didn’t know how to make it grow.

Now, with Hazloposible, we are an online hub for the voluntary sector, working with companies to boost their corporate volunteering and offering them platforms to manage and communicate this volunteering. Digitalization has obviously revolutionized our activity. Technology is in our DNA, although sometimes we are ahead of our time and launch products for which the market isn’t ready yet.

How has COVID-19 affected the voluntary sector?

Volunteering has changed. Obviously there has been a decrease in face-to-face volunteer work and an increase in virtual encounters. Some volunteering, like food distribution, still has to be done in person. But training volunteers or consulting can be done digitally. And I think that will stay even if physical volunteering comes back after the pandemic.

The citizen movement we’ve seen during this pandemic has been incredible. People and companies have initiated projects and mobilized resources to help, often informally, but these informal movements can end up establishing themselves as formal organizations or associations after the crisis, supporting the work of NGOs.

“The citizen movement we’ve seen during this pandemic has been incredible. People and companies have mobilized resources to help”

We’ve also seen companies more willing to collaborate with other companies on certain projects. So, companies have asked us to help them develop a strategic plan for a social action project that might see them partner with others from very different sectors – a bank, a utility and a retailer, for example. I’m very curious to see if those types of collaborations continue after the pandemic passes.

What’s wrong with how some companies approach philanthropy?

For me, a lot of what companies do isn’t philanthropy. A businessman deciding to donate to a personal cause, which may or may not have anything to do with the company, is not the same for me. Nor is giving blindly to a cause without taking into account any ethical considerations. And then there’s corporate social responsibility (CSR), when a business – whether selling toothpaste, building roads or being a bank – says it is now going to do things ethically. In an ideal world, the word CSR would not even exist, because companies behaving in an ethical way that contributes to society should be how it works normally.

How should companies practice philanthropy?

They should try to leverage their natural capabilities and strategic advantages. For example, it makes more sense for a company that makes software to offer training in programming for a disadvantaged population than trying to build social housing, which a construction company could do better. Whether contributing money or providing knowledge or volunteers, if the philanthropy is linked to and clearly integrated with the strategy, then the social impact will be greater.

You call for intelligent philanthropy. What is that?

It’s the opposite of giving money with your eyes closed. It used to be: “I give money to an NGO” and nothing more – a blind donation. That evolved into: “Not only do I give money, but I also want to see a report of the results.” Increasingly, it’s that, plus: “I provide added value (training, advice, knowledge, support, structures, plans) so that the money I give is used in the most efficient way possible, with measurable impacts and a continuous improvement process to make sure the social impact is sustainable.”

To some extent, intelligent philanthropy merges with social entrepreneurship, socially responsible investing and the emergence of ethical indices and new financial instruments such as social impact bonds. I depict it like a fan, with blind giving at one end and spanning all the way over to results-based investing at the other, with a multitude of things in between.

What’s the value of corporate volunteering?

It has several really positive impacts. First, it’s good for employees. It can make them happier and more motivated, increasing their sense of pride in and belonging to the company. Moreover, if companies let the employees choose the initiatives, it reinforces what many companies are trying to encourage as part of internal improvement processes: that it’s not just the management who have all the best ideas, but the knowledge and involvement of each and every employee are important.

Of course, volunteering changes the lives of the beneficiaries – kids at risk of exclusion, or a disabled person if the company decides to offer training or mentoring for groups excluded from the workplace. But it also changes the life of the employee who volunteers. Yes, you are going to help someone else, but make no mistake, the first person to be impacted is you.

Should it be allowed during work hours?

I think it depends on the values of each company. Some companies allow employees to dedicate a percentage of their workday to innovation projects, so why not to philanthropy? It’s another valid source of knowledge, inspiration and motivation. And when people work together for a common good outside of themselves, ties are strengthened and values are transmitted, which is beneficial for everyone in the company, especially for family businesses.

What is the latest initiative you have launched with IESE?

I believe that many in the IESE community would like to do something for others and give back to society. IESE is characterized by professionals with an ethical vision. Building on the idea of Hazloposible, we have created a platform to match the knowledge and experience of IESE alumni with NGOs that may need, say, a marketing plan or a financial review. This means NGOs won’t have to spend what little money they have on marketing, communication and consultancy services. By putting NGOs and IESE alumni in touch with each other to exchange their expertise in such areas, NGOs are then able to make more efficient use of their limited resources, maximize the value of donations and make an even bigger social impact. And that’s intelligent philanthropy.

Justice and charity at work

04Philanthropy: Giving back by giving away

Achieving social cohesion requires two basic attitudes that are intertwined and mutually reinforcing: justice and charity.

Justice can be defined as “each one getting their due,” not only in economic terms, but in all aspects of human relationships. This principle of “rendering to each their due” is essential for harmonious social relations, both among individuals and among the groups to which those individuals belong.

But human relationships are more complex. And as we will know from experience, fulfillment in life comes not simply from doing what we are supposed to do because people are owed, but from going the extra mile. Therefore, social cohesiveness will see justice reinforced with charity.

Charity, in turn, must be expressed from a standpoint of justice. Because, although being charitable can help you cope with the consequences of unfair situations, it must not stop you from confronting the unfairness itself.

Justice without charity can lead to cruelty, while charity without justice can be used as an excuse to ease one’s conscience. As such, there can be no charity without justice, and no justice without charity.

The same applies in the realm of business. Pope Benedict XVI raised this issue a few years ago when he tried to bring the logic of gift and gratuitousness – the idea of giving something freely, typical of charity – to the logic of the market, which is guided by the criteria of justice.

What does this mean for business?

As we highlight in this special report, philanthropy is one way of introducing charity into business logic. Let me explain.

Companies, like any good citizens, are called to contribute to the solution of the problems that affect our society

Engaging in philanthropy doesn’t exempt one from pondering the responsibility of living justice, both within companies as well as in the relationship those companies have with the societies where they operate. It would be misleading to think that a company fulfills its social responsibilities simply because it carries out philanthropic activities.

A company’s first social responsibility is to carry out its business activity in a proper way. In its relationships with employees, clients, suppliers and other stakeholders, the company must ask itself if it behaves with criteria of justice and charity. How do I treat my employees? Do I pay my suppliers on time? Do I fulfill my commitments to my clients? No matter how many philanthropic activities a company engages in, everything will ring hollow if the company fails to comply with its foremost obligations to its immediate stakeholders. It would be like the person who gives money to a person living on the streets yet fails to pay taxes.

However, as stated earlier, just doing what we are expected to do is not enough: we have to go further. Indeed, the vast and complex problems facing us today demand it. “Justice” in companies may be interpreted as compliance with our first-order responsibilities, but we have to expand our concept of what we do, beyond our direct business activity, to include charity or gratuitousness. What resources, talent and capacities do we have that could contribute to the development and betterment of society?

Philanthropy is a way of realizing this. Companies, like any good citizens, are called to contribute to the solution of the problems that affect our society. And as this report makes clear, there are many different approaches out there, with recognized resources for deciding how to donate and which actions might be appropriate for you to take.

Many of the world’s problems may demand strict answers of justice. But, as Benedict XVI stressed, there will always be situations in which charity is needed, because people, beyond justice, have and always will have a need for love.

Joan Fontrodona holds the CaixaBank Chair of Sustainability and Social Impact at IESE Business School.

This Report forms part of the magazine IESE Business School Insight #158. See the full Table of Contents.

This content is exclusively for individual use. If you wish to use any of this material for academic or teaching purposes, please go to IESE Publishing where you can obtain a special PDF version of this report as well as the full magazine in which it appears.