Retail Revolution

01Retail Revolution

Digitalization, the pandemic and climate crises, supply-chain disruptions and inflation have shaken up retail. And despite the push to get back to normal, for retail, normal doesn’t exist. As the boundaries between online and offline shopping blur into one, here is how retailers can prepare for an omnichannel future.

“One of the biggest constraints on consumption is when consumers stay home. If customers no longer visit stores on a regular basis, they increasingly buy online. This demands a multichannel strategy that uses every possible channel – e-commerce, smartphones, social media and reinvented physical stores – to keep the customer surprised and deliver a seamless shopping experience.”

So wrote IESE professor Jose Luis Nueno in his 2013 IESE Insight article, “The decline of Main Street, the rise of multichannel retail.” At the time, he was describing the retail landscape six years after the 2008 global financial crisis. But he might as well have been describing today.

The fact that this situation was evident in retail a decade ago helps explain the choice of title for Nueno’s recently published book, Never Normal. Because even though the 2020 pandemic was an abnormal event, its effects on retail will come as no surprise to anyone who has been paying attention. Now, as the world talks about getting back to normal, Nueno says we’d be better off accepting that “normal” doesn’t exist: “If the last two years have taught us anything, it’s that the only thing ‘normal’ is a continuous series of shocks and disruptions, and the disruptive forces that have been particularly difficult for retailers over the past decade are not going away; the only ‘normal’ thing to do is adapt, evolve and reinvent yourself to survive.”

We share tips from industry experts on how to face the future with tenacity, flexibility and agility

In this report, we look at some of main forces shaping retail, of which the pandemic was only the latest, sharpest shock. Of those forces, technology and digitalization have certainly played a, if not the, defining role, and we highlight how retailers can use tech to their advantage, based on IESE research. We also consider how those forces play out in different cultural contexts. We share tips from industry experts on how to face the future with tenacity, flexibility and agility. Because even among those retailers who may have prospered during the pandemic (supermarkets) as well as those who are seeing business roaring back to pre-pandemic levels (restaurants, hotels, airlines) we appreciate, now more than ever, that life can turn on a dime. War, geopolitical divisions and inflation, on top of unpredictable coronavirus variants, mean anything can happen anytime, so having the right competencies counts as much as the right strategies for facing the challenges ahead.

Forces shaping retail

Long before 2020, business pundits were warning of a Retail Apocalypse, mainly due to the rise of e-commerce, which threatened to put many traditional retailers out of business. Particularly for small and medium-sized retailers, the outlays required to invest in online operations in addition to their physical stores were just not viable, especially when online sales growth was not (and in some cases, still isn’t) high enough to justify the extra expenditure. “Multichannel” meant “being all things to all people,” a move that some retailers regarded as spreading themselves too thin at a time when the rewards of doing so were also seemingly thin.

Time has proven that the shift to e-commerce, for those who managed to do so, was none too soon. The 2020 lockdowns prompted an overnight shift to online purchasing and delivery of goods and services. As a spokeswoman for the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development remarked, “Businesses and consumers that were able to ‘go digital’ helped mitigate the economic downturn caused by the pandemic … and they have also sped up a digital transition.”

Yet there’s more to this digital transition than meets the eye. It’s not clear whether the e-commerce boom provoked by the pandemic was a one-off phenomenon, and pent-up consumers will revert to shopping in stores as soon as they’re given the chance, which is what we’ve seen so far since lockdowns eased.

Retail by phases

Where we’ve come from, where we’ve just been, and where next…

Phase 1: Talk of Retail Apocalypse

- Traditional retail struggling due to discounters, online competition, changing demographics and unsustainable growth, but not catastrophic yet

Phase 2: COVID-19 lockdowns

- Everything except essential retailers forced to close

- A complete break from old shopping patterns

- The Great Dispersion: asynchronous shopping activity

- Triumph of delivery and local stores

Phase 3: Vaccination campaigns

- Slow re-openings

- Staggered recovery due to lack of stock

- Consolidation of online channels

Phase 4: Start of recovery

- Return of physical sales as people flock back to the shops, but more fragmented now

- With regard to e-commerce, a case of 3 steps forward, 1 step back

Phase 5: Resumption of previous shopping habits but with changes

- Peaks (pent-up demand/money saved over 2 years now being spent) but also troughs (people have different priorities, spending less on things than they did before, having realized they can do without)

Phase 6: Repositioning

- Cost of living crisis, threat of recession

- Less discretionary spending: consumers either won’t buy, they’ll buy cheaper products, or they’ll shop in discount stores

- Sacrifices to sustainability agenda?

As Nueno points out, it wasn’t the average shopper on the street who was warning of an impending Retail Apocalypse but rather the stock market analyst. “And interestingly, if you look at European retailers listed on the stock market that weren’t purely digital businesses, you find they have outperformed the rest of the traditional indexes by almost 300% over the past decade. With a few exceptions (like Amazon, Zalando, Alibaba or Shein), pure online retailers remain unprofitable, with their growth rates propped up by investors.”

Indeed, until 2020, consumer spending in physical stores was still predicted to outperform online sales until 2030. Besides books, music and video, no other retail category has achieved more than half its sales through e-commerce alone, and even for those that have, it has taken 20 years to get there.

This is not to dismiss e-commerce as a major force affecting retail. Certainly, it is. But as Nueno urges, we need to dig deeper to get at the forces driving e-commerce; otherwise, the temptation would be to pile all your resources into online sales at the expense of everything else, which could be counterproductive.

Digging deeper

Pandemic aside, perhaps the bigger disruptive force dictating the future of retail is demographics – namely, millennials and Generation Z, who make up major segments of the world’s population, most of all in Asia, which has six times the number of millennials as the United States and Europe combined. They are prone to purchase for experiences and according to values such as sustainability. They are also used to buying online and paying via smartphone. It will be this consumer reality that ultimately drives the future of retail.

Does that mean it is time to wholesale embrace m-commerce, for example? That depends on what your consumer base is telling you. A 2021 IESE survey of 1,646 online shoppers representing Gen Z, millennials and Gen X in Spain found a sizeable 75% had bought items over the past year via their mobile phones. Thus, a Spanish retailer that doesn’t have a mobile-friendly option (let alone any form of online store presence) may find such a statistic galvanizing in a way that a different retailer, subject to different market forces, may not.

Perhaps the bigger disruptive force dictating the future of retail is demographics

In reading market forces, the key for retailers is to think twice before jumping on bandwagons or riding whatever the current wave seems to be. For instance, when doomsayers were predicting a Retail Apocalypse a decade ago, it was mainly in reaction to the rise of Amazon. But the business takeaway is not for all retailers to jump on board Amazon. Rather, it’s to reassess your own market landscape and make strategic choices befitting you. (As Nueno says later in his column, setting up your own direct-to-consumer channel may be more profitable and necessary than selling via Amazon.)

Phil Douty is Global VP, Intent xChange, at Intent HQ, the customer intelligence platform that sponsors an IESE Chair, currently held by Nueno, on Changing Consumer Behavior. As Douty told Mobile World Capital Barcelona 2021, market metrics have changed dramatically in recent years, making it more important than ever to get to grips with them: “Under every current trend there are typically other things going on that are driving the behaviors that you see on the surface. Take the trend of people going back to the office: employers would like to think it is because they love the office environment or because they want to be with their colleagues, but for some people it is the opening of bars and restaurants that is one of the drivers returning them to the office. That’s what I mean by getting under the skin of the trends that you see: groups of people may collectively exhibit the same behavior but actually for very different reasons.”

“Likewise, when you look at behavioral segmentations, there are groups of people for whom ‘service’ means very different things. For example, somebody working from home prizes certain aspects of IT service in a very different way from somebody who uses their IT system for gaming. Different cohorts of consumers will value different things about your service in different ways. What’s good service to one group is bad service to the other, and vice versa.”

Referring back to the behavior of online shoppers in Spain, that same survey found 64% wouldn’t pay more for an environmentally friendly product or service, and of those who would, most wouldn’t go beyond a 10% price premium. This, despite the majority of that same generational cohort expressing concerns about climate change and the environment. What’s the conclusion to be drawn here? Proof that retailers should abandon efforts to go green? Not by a long shot! (See the interview with Claire Bergkamp, Eva Kruse and Andrea Baldo for more on this point.)

Douty insists, “It’s really important to understand the differences in order to be able to produce the outcome that each of those distinct cohorts of customers might wish to see from you.”

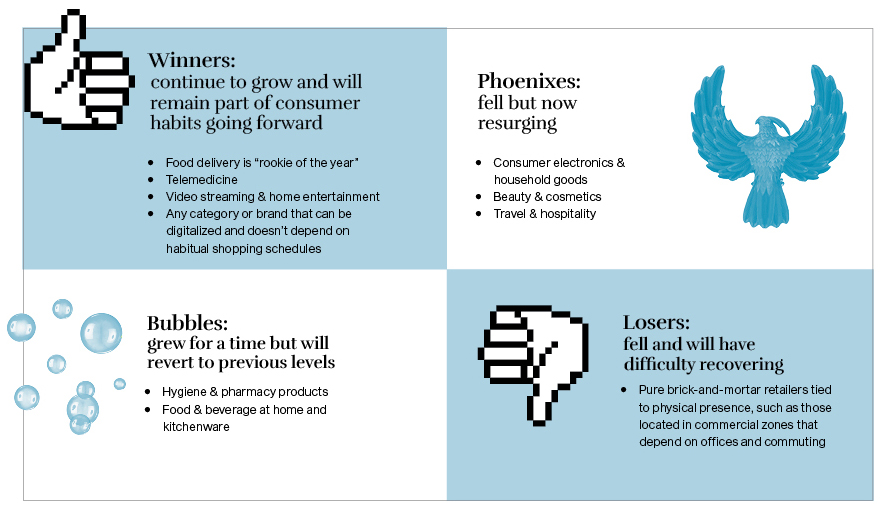

COVID’s impact on consumer interests and behavior

SOURCE: Based on a 2020/21 study of the online searches of 14 million people, by J.L. Nueno and Alfonso Urien of the Centre for Data Insights, a partnership between IESE and Intent HQ.

Read related interview with Jonathan Lakin, Founder and CEO of Intent HQ, published in IESE Business School Insight #156: “Companies that design for difference win every time.”

Making the most of data

Getting under the skin of today’s trends to tease out the nuances of consumer behavior is what Intent HQ specializes in, using proprietary AI to glean customer insights for business clients. “Data is no longer generated as an ‘exhaust’ of the way we live our lives but is actually the way we live our lives. The management of near real-time data and data insights has got to the stage where every company can be data-centric in its decision-making, provided it harvests and harnesses that data in the right way,” says Douty. “The issue is no longer tech-related but an operational one to manage and interpret the signals.”

IESE professor Victor Martinez de Albeniz agrees. He has done extensive research on using data to optimize operations in retail, particularly within the fashion industry. “For the first time in history,” he says, “retailers have the opportunity to understand and predict customer behavior at a granular level, tracking every click and every step of each individual at all places, and gathering data not only on their interests, decision processes and purchases but on their plans and intent of purchases.”

Armed with such information, retailers can see how products are performing in real time and make price adjustments that better match supply and demand, boosting profits in the process. To demonstrate this, Martinez de Albeniz studied “flash sale” retailers. These are not platforms like Amazon that stock third-party goods and occasionally offer sales; these are online outlets that only sell discounted goods for third parties that are trying to get rid of their out-of-season inventory. Players in this space include the Chinese leader Vipshop, the European leader Veepee (formerly Vente-Privee) and American players such as Rue La La, Zulily or Gilt. They’re called “flash sales” because products are sold fast for a very short period of time, maybe three to seven days, until stocks run out. These retailers do not control their own inventory, and demand is extremely volatile, which makes what they do control – pricing – a key lever. Despite that, few seem to adjust their prices much during their sales campaigns.

Retailers can see how products are performing in real time

Here is where data can help. Martinez de Albeniz and his co-authors built a model that they validated with real data from a leading flash sales retailer in Western countries, using hourly events over three years. They used clickstream data – that is, all the clicks made by a potential customer, between arrival to the website and visiting a particular campaign, between visiting a campaign and interest in a particular product, even when there was no final purchase of that product. This is key, because it shows the rich insights that retailers can still learn about visitors to their website, enabling them to forecast probable actions that those visitors might take during the shopping process, and thereby take corrective actions. So, by breaking down each step in the buyer journey, retailers can determine whether a better product description, a more attractive image or even the time of day, for example, would improve the conversion rate from campaign visit to product click. Then, they can apply adjustments within hours, and measure the impact of those interventions.

In their study, published in Production and Operations Management, the authors discerned the optimal price adjustments to make, and when, for different products, both those selling zero units and those about to sell out. In this way, retailers can “set prices so that supply and demand are more closely matched.” So, for a lower selling item, a price increase of 58-65% could improve profits by 12-16%, whereas for a high-demand item likely to sell out, a steep price increase (94% on average) would result in the strongest profit improvement (73%) according to their study of 10 campaigns involving 4,512 products. If their pricing recommendations were applied across the board, the total revenue increase would be 27%.

The authors note that their model’s applicability is not restricted to online retailing: “We can apply a similar approach to choices made in physical stores, where customers follow a predefined shopping funnel from the main entrance to the checkout, taking sequence-dependent actions.”

Many retailers remain slow to change their old ways – at their loss

Despite compelling evidence that data-based decision-making can make retail operations more efficient and profitable, many retailers remain slow to change their old ways – at their loss. This is highlighted in other research by Martinez de Albeniz’s operations department colleague Anna Saez de Tejada Cuenca, with UCLA Anderson’s Felipe Caro (forthcoming in Manufacturing & Service Operations Management). They studied managers’ use of algorithm-based decision support systems (DSS) for seven clearance markdown campaigns at Zara. The algorithm made recommendations, but it was up to the human managers to adopt or override them.

In a pilot test, Zara found that managers who followed the DSS recommendations increased revenue from clearance sales by almost 6%. That led Zara to roll out use of DSS across its stores and franchises worldwide. But then something changed: managers started ignoring the DSS recommendations, sometimes more than half the time; moreover, they would lower prices when the system recommended keeping them the same, or they would apply more aggressive markdowns than what was recommended. The result: sales revenues were less than expected.

What happened? Human biases kicked in. Specifically, managers were used to receiving weekly reports showing current inventory levels and they typically made decisions aimed at ensuring that nearly all remaining stock was sold as soon as possible. The DSS, however, made recommendations with the goal that overall revenue would be higher at the end of clearance sales, and that could mean more conservative markdowns in the initial periods. Yet, if managers’ attention was focused on inventory, then they naturally ignored the algorithm. Zara was not alone in experiencing this: past research involving a consumer electronics firm found its managers overrode DSS recommendations more than 80% of the time, also for peculiar human reasons.

How can managers make the most of algorithm-based decision support systems?

“It is critical that we understand how human decision-makers interact with such tools to design them in a way that entices managers to adhere to their recommendations,” insists Saez de Tejada. Namely:

Status quo bias: Recognizing that humans are generally reluctant to change, analytics tools should make clear the logics behind the recommendations, especially those that deviate from the previously accepted rule of thumb. Decisions can be benchmarked from one season to the next, so managers can see the performance of the new action taken compared with decisions made the old way. This can help educate managers to accept changes and build trust in the DSS.

Salience: Figure out what the salient metrics are for managers (inventory vs. revenue). If actions seem counterintuitive (e.g., less aggressive markdowns may lead to slower sales but more revenue overall), these can be explained and supplemented with additional dashboards that compare/contrast the forecasts of different actions according to the salient goal.

The cost of attention: Managers only have so much cognitive capacity. The DSS should simplify choices as much as possible, so managers don’t have to track vast reams of data across hundreds of different categories or make too many choices simultaneously. Although Zara managers understood that the DSS was a tool to simplify their lives, the majority were more likely to deviate from the tool’s output when they were overwhelmed with too many pricing recommendations to check.

In light of these biases, Zara subsequently revised its dashboards, with better results. “Providing not only feedback on managers’ realized revenue, but also making such feedback more interpretable, had a strong, positive effect, increasing the adherence of those who used to override the tool the most,” state the authors.

Cultural dynamics

Salience is a keyword for retail, especially when operating in diverse markets around the world and determining which features of your retail strategy will be most salient to a particular market. There’s no one-size-fits-all approach. What works in the United States may not resonate in Japan.

This emerged in research by IESE marketing professor Elena Reutskaja. The received wisdom is that consumers today suffer from too much choice, paralyzing them at the moment of truth. This has led some retailers to reduce their product lines in the belief that offering fewer products can boost the sales of those that remain. The pandemic encouraged further moves in this direction. Supply-chain disruptions and stockouts forced many to pare down their offerings. And as retailers come under mounting pressure to trace the supply chains of each and every product in order to fulfill ESG reporting requirements, having fewer products makes that job easier.

Does too much choice necessarily lead to consumer dissatisfaction?

Despite the arguments in favor of reducing choice, Reutskaja raises some important qualifiers. The idea that too much choice necessarily leads to consumer dissatisfaction is largely a U.S. phenomenon, and even then, it depends on what choice: being spoiled for choice of soft drinks is not the same as a choice of jobs, schools or doctors.

Reutskaja and her coauthors studied 7,400 participants from six countries that collectively represent nearly half the world’s population: Brazil, China, India, Japan, Russia and the United States. Besides trying to quantify the relative dissatisfaction of too much or too little choice in those different markets, she distinguished between commercial choices and consequential ones, as just described.

So, while too much choice was primarily a U.S. problem and mainly in commercial domains, that finding did not hold true across the board. In Japan, for example, a huge number of commercial offerings didn’t actually result in feeling overwhelmed; and in other countries, consumers were not as dissatisfied as when choice was in short supply. Overall, too little choice was the bigger problem than too much choice, especially when it came to consequential choices.

For retailers operating globally, it’s worth remembering to contextualize product offerings, as the link between the number of choices and subsequent (dis)satisfaction may have a cultural dimension. When making strategic decisions to cut, keep or expand SKUs, consider the cultural nuances surrounding choice. As with everything, retailers need to drill deeper to get at the underlying forces at play.

Expanding on this point, Nueno adds that, while Western retailers grapple with the digitalization of their physical operations, in Asia it is largely the opposite problem: many Asian retailers launched digitally, without any legacy stores, so there the omnichannel model poses distinct challenges related to the establishment of physical touchpoints.

Digital supply chain: Just do it

The rise of digitally connected consumers, particularly those in Asia and Latin America, is revolutionizing retail strategies to serve customers faster and more personally, at scale. Nike, for instance, has upped investments in RFID and analytics as well as robotics and automation, while moving manufacturing plants closer to consumers. It leverages its apps to capture demand signals and pre-orders. It has also invested heavily in developing its own direct-to-consumer channel, moving away from undifferentiated retail and toward environments where it can better control the consumer experience.

Nike’s growth in digital does not supplant its stores. As CEO John Donahoe explains, “Customers don’t necessarily just want to buy digitally and have it shipped to their home. What we saw during the pandemic – and we believe it will continue – is that they want to buy it on their digital device and go pick it up from the store. Or with soft goods like apparel, they may want to reserve it online and try it on in the store. Consumers increasingly want a consistent, seamless physical and digital experience, and so that’s what we’re committed to providing.”

Recognizing the customer journey is becoming more fluid and omnichannel – or O2O (online-to-offline and offline-to-online) – Nike recently embarked on a radical digital transformation of its supply chain, starting with a pilot program in Europe. This was partly driven by the need to satisfy online consumer expectations of deliveries in two days or less. It involves creating a multi-node network of hubs, rather than one central warehouse, to dispatch products closest to the consumer. Logistics decisions are informed by digital intelligence, anticipating and recommending where best to place inventory to fulfill demand, and consolidating shipments as much as possible in support of Nike’s strategic commitment to reducing CO2 emissions.

Nike’s experience shows how a digital supply chain can truly leverage the interrelationship between different business areas, “so we can deliver products in a low-cost, convenient, speedy and climate-friendly way,” says Donahoe.

SOURCE: The case study “Nike supply chain in the new digital age” (P-1199-E) by IESE professor Joan Jané and Pedro Ferrinha (MBA ’21) is available from IESE Publishing.

Key competencies

Managing both physical and digital channels. Determining pricing strategies amid inflation. Using tech to personalize offers. Minimizing supply-chain disruptions. Differentiating the brand. Moving to an omnichannel model. And making the staffing and organizational changes necessary to deliver on all these priorities. Managing all these factors in a highly uncertain business environment makes the CEO agenda more daunting than ever, as confirmed by an IESE survey of Spanish business leaders.

Yet, viewed another way, none of this is new. The history of business in general and retail in particular has always been a case of survival of the fittest. “The retail industry has always been fraught with blood, sweat and tears, forcing retailers to remain creative and innovative or perish,” says Martinez de Albeniz, echoing the same sentiment of Nueno’s book, Never Normal.

“The retail process has undergone significant transformation since the 1800s. The ‘best practices’ constantly change, driven by rents, labor and logistics, as well as the appearance of new technologies that change both the nature of the work to be performed and the nature of the ‘winning’ store format. Given its intricate connection to external conditions, retail never has any choice but to adapt or go extinct.”

The future is phygital

The seamless integration of both physical and digital channels is the next iteration of omnichannel.

By Dimas Gimeno

The author is the former head of Spain’s leading retailer, El Corte Inglés, and more recently founded the WOW concept store in Madrid. He also leads the investment firm Kapita, which targets retail-related tech projects.

Although retailers have been talking about omnichannel since 2010, the vast majority of trade remains physical. Even among those who claimed to be omnichannel, they really weren’t. Instead, what we saw were attempts to add some digital component to the legacy physical store operation. But there wasn’t a paradigm shift of actually merging physical and digital assets under a single, integrated vision, because changing existing systems and processes, and selecting and training new profiles to manage them, represent an uphill battle.

However, there’s no getting away from the fact that digital connection is what characterizes today’s consumers, with e-commerce providing access to goods and services like physical stores used to. The retail of today and tomorrow must focus on two vectors: the emotional connection (with the brand, product, service or experience) and the digital one (a seamless integration of both physical and digital channels). I call this “phygital.” This thinking was behind the launch of WOW, which I like to define as a phygital experience platform.

I consider phygital to be the next iteration of omnichannel. This time, the integration is being done from the digital side, with physical assets (points of sale) adding the value. That changes the perspective. Web and mobile apps let customers project the digital environment onto the physical store. People go to the store with their digital baskets, read and share QR codes, live-stream their shopping and interact with others via social networks (Live Shopping) – all of which enriches the shopping experience as buyers and sellers both gain more information about each other.

Phygital is not just for the larger stores but also applies to small and medium-sized retailers. Ignoring the digital reality will put you at a disadvantage with those that have the digital side that all customers have come to expect. Indeed, going phygital could even be easier for smaller retailers versus those with large, established operations. Apart from the necessary financial investment, the important thing is to transform your culture into an authentic phygital one. Whether starting with physical or digital, your transformation must reach all employees and ensure no cracks in the customer experience.

READ MORE: “Adopting a retail phygital experience via open innovation: the story of WOW” by IESE professor M. Julia Prats.

As such, Martinez de Albeniz and Nueno highlight three enduring competencies for retailers, inspired by Stanford’s Hau Lee, whose influential research on what truly great companies do to stay ahead of their rivals remains as relevant as ever.

Agility. Rapid adoption of innovations for store management together with a flexible, opportunistic market strategy are keys to survival. This does not mean sacrificing a strong brand identity rooted in a steady purpose. It means constantly scanning the external environment to detect new consumer needs and new operational processes, and then being able to respond quickly to sudden, unexpected changes in demand. (See the interview with Oscar Garcia Maceiras for how Inditex uses technology to be more agile.)

Adaptability. If agility is about your rapid ability to respond to demand shocks like COVID-19, adaptability is about adjusting complex systems – like the supply chain, organizational assets (factories, warehouses, logistics, stores) and technologies – in a reasonable amount of time so as to be fit for the future. The shift to omnichannel, for example, is something that no retailer can ignore, and they need to be moving their organizations, people and cultures in that direction sooner rather than later.

Alignment. The omnichannel reality, and the intermingling of physical and digital realms, will require a corresponding intermingling of many departmental roles that were previously discrete. Marketing, sales and operations, for example, must work in close alignment, reflecting the changed nature of the customer journey. (This came out in the survey of Spanish CEOs.) Being agile and adaptable is much harder to achieve without organizational alignment, which ensures that everyone is rowing in the same direction.

These so-called Triple A’s will likely carry retailers through whatever new challenges lie ahead.

The good news, as Nueno notes, is that the retail sector continues to show remarkable resilience. “The debate is not between physical and online stores but rather what is the role of stores: Collection points? Showrooms? Local distribution centers? Places for experiences? Just as stores cannot be understood without some form of e-commerce, neither will it be possible to deliver on e-commerce without the logistical efficiency and the capacity to create strong brands that large stores are capable of.”

“What the post-pandemic period has made clear is that there are not two groups of consumers: those who will go back to stores and those who will only shop online. The pandemic has served to create a critical mass of consumers who are now disposed to do both. More than the fact of an e-commerce option is the consumer expectation that there will be such an option, and there will be little future for any retailer that denies its customers the possibility of buying whatever they want, via any channel they want, whenever they want. This omnichannel reality is something retailers will have to reckon with.”

Are you ready?

“Scenario planning in high-uncertainty environments: the disruption matrix” (MN-405-E), by Carlos Costa and J.L. Nueno, is a framework for companies to develop their own medium-term scenarios and design action plans to tackle the main management trends related to digitalization, omnichannel operations, organizational agility, brand-building and sustainability in a post-COVID world. It is available from IESE Publishing.

Retail Trends

02Retail Revolution

The future is VOLATILE

Strong brands Inflationary pressures benefit private labels in many cases, though strong name brands that innovate and add value are likely to be recession-proof.

Fast delivery From 48-hour to 24-hour to almost instantaneous, customers demand speed. Can your business keep up? How will you manage wait times and customer expectations? Could “slow” models become the new fast?

Clarity of purpose Consumers want to know who is behind their products and what their values are. Cultivating a stable purpose will make your business more sustainable.

Demand shocks Just as grocers flourished while the hospitality industry crashed in 2020, sudden and surprising peaks and troughs in supply and demand are likely to continue for the foreseeable future, not only as a result of the pandemic but from the climate crisis.

The future is OMNICHANNEL

Value-added brick-and-mortar Fewer physical stores, but those that remain will evolve into showrooms for connection, discovery and/or collection.

The metaverse Though we’re not here yet, virtual reality (VR) tech may let brands experiment and learn from customers, allowing them to try out new goods virtually, for example, and offering more sensory experiences. Watch this space!

Click-and-collect For those who like the convenience of online shopping, but prefer to pick up goods at the store, curbside or from a locker, without waiting at home for delivery. This also saves logistics costs for the retailer, with one or a few drop-off point(s) rather than many delivery locations.

Seamless experiences Customers want to be able to shop in-store and online; to try things on in-person and buy things sight unseen, knowing they can always return them. Customers prioritize convenience, whether of sales, pickups or returns. On- and offline channels need to be fully integrated.

The future is PERSONAL

Shop local As consumers rally to save local businesses from pandemic-provoked closures, and as sky-high gas prices make driving less desirable, shopping in your local community becomes added value. Big stores can benefit, too, creating boutique presences in key neighborhoods.

Subscription models The subscription model, selling everything from movies to clothing, can help brands curate customer experiences. But, as we’ve seen with Netflix, beware the slide into too much undifferentiated content. When times are tight, consumers cut subscriptions that don’t add value.

On-demand manufacturing This affords opportunities to eliminate overproduction, redundancy and waste in supply chains.

Customization From clothing to video games, brands are directly engaging with and seeking input from users for co-creating products tailored to their specific needs.

Interview with Oscar Garcia Maceiras

03Retail Revolution

Oscar Garcia Maceiras became CEO of Inditex in November 2021, the same year he joined the company as its general counsel and board secretary. A Spanish State Attorney in his home region of Galicia (where Inditex is based), he comes with over 20 years’ experience in legal affairs. He did a PDD at IESE in 2008 and is currently pursuing a PhD in International Law.

Coming from a background in legal affairs and finance, Oscar Garcia Maceiras faced a change of pace when, in 2021, he moved to the customer-facing world of retail. He now heads Inditex, the Spanish fashion conglomerate famous for Zara. After the economic havoc wrought by COVID-19, like many retailers Inditex has seen “a significant rebound in traffic to stores,” he reported in June 2022, noting that net income had increased 80% to 760 million euros during Q1 2022 compared to the same period of the previous year.

Here, he discusses the success factors of retail at a time when customers and the global outlook are more demanding than ever.

How are you adapting to the changing needs and buying habits of customers? And what’s the role of technology in this?

This is a moment of profound transformation, which demands creative thinking from retailers as a whole. At Inditex, we’ve always tried to put the latest technologies at the service of the business model. Technology is key to understanding our customers in order to offer them the products they need and want at just the right moment. And technology has enabled online sales, which now account for 25% of our total sales and are forecast to reach 30% by 2024.

Technology doesn’t mean abandoning the physical store, however, which is a technological space just as much as our online sales channels. We’re committed to integrating physical and online channels, which are two sides of the same coin. Put simply, physical and online spaces shouldn’t be in competition with each other, they should be generating synergies.

A good example is the flagship Zara store that we inaugurated in April 2022 in Madrid. It incorporates the latest technologies available to improve the shopping experience. For example, customers can use the Zara app to geolocate products or book a fitting room. There are self-checkouts and automatic collection for purchases made online. Technology facilitates an integrated inventory management system so that online orders are expedited with maximum efficiency.

Which factors are fundamental to success in retail?

In the case of Inditex, I would say four: the quality of the offer, which is born from a combination of creativity and listening to customer needs; a continuous effort to make the shopping experience unique; sustainability, which should be present throughout the value chain and in the worldview of the company; and, most of all, people.

“Physical and online spaces shouldn’t be in competition with each other, they should be generating synergies”

At Inditex, that means 165,000 people of 177 nationalities, 76% of which are women who in 2021 held 81% of our management positions. We try to make sure that all these people, who are so different from each other, can develop their passions and keep improving themselves.

Equally important to attracting talent through specific recruitment programs is retaining that talent by providing opportunities for continuous learning and growth within the company, and with training in our corporate culture and values. Through our Changemakers program, for example, we develop and equip certain employees to become ambassadors for our corporate strategy of sustainability within every one of our more than 6,400 stores worldwide.

Where does sustainability fit?

Sustainability affects all processes, decisions and projects. We’re following a very rigorous roadmap to reach 100% renewable energy in operations, as well as sustainable fibers and materials. The goal is to reach net zero by 2040.

To get to net zero, it’s essential to invest in innovation and research. For us, this includes our Sustainability Innovation Hub, an open platform to develop new materials and industrial processes. We’ve also made significant agreements to acquire recycled textile fibers, including an agreement of over 100 million euros with the Infinited Fiber Company. In terms of research, we collaborate with leading universities such as MIT. And we have recently invested, for the first time, in a startup, Circ, which has technology to enable large-scale textile recycling.

How can retailers encourage more social and environmental responsibility in their operations?

Speaking from the perspective of Inditex, by becoming an agent of change. We are very demanding of our suppliers and try to bring them along with us as we seek to raise environmental and social standards. We want to lead the transformation of the industry through responsible management in collaboration with a good number of organizations, including IndustriALL, the international trade union federation with which we have a pioneering Global Framework Agreement to put the worker at the center, promote continuous social dialogue and ensure optimal labor standards.

What’s the key to keep reaching customers who are more informed and demanding than ever before?

There’s no infallible formula but it helps to have a model that prioritizes listening to customer needs, along with a top-level design team (of 700 professionals, in our case). Our brands all pursue the same goal: to offer the best products to our customers. Creativity, emotion and surprise underpin everything we do – from the shopping experience, to the strategy of sustainability, to our community relationships, to the workplace environment that we provide.

Changing the system

04Retail Revolution

Changing the retail model must be driven by management. Although there is a segment of consumers who will buy on the basis of sustainability, for the most part, such demand isn’t enough to make retailers deviate from the existing model of disposable overproduction. Which is not to say that sustainable retail cannot be profitable, but it takes greater imagination.

This is where Claire Bergkamp and Eva Kruse come in. Bergkamp is Chief Operating Officer at Textile Exchange and was formerly Worldwide Sustainability and Innovation Director at Stella McCartney. She helps retailers improve their sourcing practices to reduce emissions in the raw material production phase by 45% by 2030.

As Senior Vice President of Impact for Pangaia, Kruse works with scientists to develop responsible replacements for existing materials, including a bio-based replacement for nylon.

Both of these leading sustainability advocates shared the big changes on the horizon for retail as part of an MBA course on “Strategic Management in the Fashion and Luxury Goods Industry,” taught by IESE professor Fabrizio Ferraro and Andrea Baldo, CEO of Ganni.

Here is what the future holds for retailers, according to Bergkamp, Kruse and Baldo.

Aren’t companies already working to reduce their energy use and carbon footprints?

CB: There have been efforts to reduce downstream emissions – those at Tier 1 where products are finished and distributed to consumers. But the Tier 1 stage accounts for only around 9% of the overall environmental impact. The vast majority of the impact lies upstream in Tier 2, where fabrics are made, at 52%; in Tier 3, the processing of raw materials, at 15%; and in Tier 4, the cultivation and extraction of raw materials, at 24%. That is why we work with organizations to address the earliest parts of the chain: how cotton is grown, the cutting down of forests, the turning of raw materials into fibers. Many know their Tier 1 but very few know beyond that. And that is where the largest challenges and opportunities lie.

We prefer to talk about Climate+. It’s not only about reducing greenhouse gas emissions and recycling waste but thinking about how to prevent waste from being generated in the first place. It’s a whole system change.

How do we do that?

CB: First, we have to slow growth. This is not something that brands like to talk about, but it is an absolute necessity. Right now, we are around a 3% year-on-year growth of new fibers and materials coming into the marketplace. We are not going to hit climate reduction targets unless we slow that to at least 1%.

EK: I agree, we must decouple growth from volume growth of new product.

How is it possible to increase profitability without producing more product?

EK: Circularity is key. Repair, remake, reuse, resale and rental models provide a lot of opportunity. Making many more transactions on the same product is an emerging market that companies need to explore. If I can sell the same T-shirt five times, why wouldn’t I want to do that, instead of producing five new ones? It’s thinking about how to continuously create more value but decoupled from just producing more units. This is the trend of the future.

“Circularity is key. This is the trend of the future”

CB: Material substitutions are another important lever. So, taking things that already exist and regenerating them. By that, I don’t just mean taking waste, like plastic water bottles, and turning that into polyester, because that polyester is not recyclable, and so you are just extending a waste stream instead of closing it, which is what we really need to do.

Currently, only around 1% of textiles are recycled back into textiles. Polyesters are by far the most used material in the world, accounting for around 52% of all the fibers used annually, and while 14% are recycled, that comes mainly from discarded plastic water bottles. To get beyond 14%, we are going to have to figure out a new feedstock.

Where does the incentive come from?

EK: In Denmark, as in other countries, we have a deposit scheme for bottles. You pay a little bit extra when you buy bottled drinks, and you get that money back when you bring the empty bottle back for recycling. I believe we should have takeback systems like that for every product we use, whether household goods or clothes, which incentivize us to extend the life of goods instead of them ending up in landfills.

Here is where we really need policymakers to pass regulation that would require everyone to collect way more waste than they do now.

CB: Legislation would help. The biggest legislative push right now is on transparency, traceability and footprinting, which is going to become mandatory in the not-too-distant future.

In my previous job at Stella McCartney, I was involved in product environmental footprinting to try to create a label for fashion akin to the energy star rating when you buy an appliance. What such a rating does, in theory, is start to cut out the worst offenders. In electronics, the very low rated products have started to disappear completely. And whereas the top mark used to be A, now you have A+, so it also starts to push the bar higher. Granted, measuring the fashion footprint is not as simple as measuring how much electricity you’re using when you plug something in.

As I said before, what we really need is a lower impact replacement for polyester and conventional cotton, and which regenerates soil health and pays farmers well. Legislators are still trying to grapple with this, but one way or another, we’re going to see footprinting and a change in the way the market is regulated. Governments, especially in Europe, want clarity to protect consumers – not vague claims of something being sustainable, but provable impact. Cutting out greenwashing is where governments are moving. Legislation is ramping up.

Are companies ready for this?

CB: If you don’t know where or how your things are being made, that’s a red flag. We would like to think that is not happening but there are still places in the world where that is the case. If CEOs took just a third of the time they take to understand their retail strategy to understand their impact – acquiring full knowledge and control of their entire value chain – we would be in a very different place. Is this a concern of your top management? Is sustainability something that has been sidelined or is it a core mandate of your company? Because it should be. It’s well past time, for any company operating today, to consider their impact on humans and the planet as a side topic. The people in charge of making the decisions – the CEOs, the boards – need to wrap their heads around this.

“If you don’t know where or how your things are being made, that’s a red flag”

EK: It’s really a management decision as to how much they want to push the market on this. Let’s face it, most consumers are acting on whatever is convenient or a good price. A choice of outfit for going out on Saturday night is not because they’re trying to save the planet, it’s because they want to look nice and wear something new. For that reason, change has to come from the industry and to the consumer, so no matter what they buy it’s a given that it has been made responsibly.

Unfortunately, there is a very profitable business model in overproducing, in overconsumption, and then marking things down. I wish we could regulate markdowns in terms of the lowest price that would be acceptable relative to how much land, natural resources and human labor were exploited in the process of making it. Maybe then we would appreciate its actual worth. Again, it comes back to a choice from the leadership of the businesses how far they are willing to go on this.

Are discount retailers to blame?

EK: I’m not against producing clothes at a cheaper price point because not everybody can afford expensive brands and there need to be opportunities for families with other wallets to access products. With fast fashion, for example, it’s not so much the price point that’s the issue, it’s the disposable part.

CB: Fast fashion has become synonymous with “affordable and disposable,” but those two things need to be separated, because I believe there is space for affordable fashion, just not disposable fashion made to be worn once and thrown away. As a society, we have to completely remove the idea that disposable fashion is acceptable. Yet there has to be a place for responsibly made affordable fashion.

However, producers must ask: Is this product going to be used for a long while or a short time? Durability should be their highest calling, but if they’re making basics, like undergarments, then they need to ask: What’s going to happen to that afterwards? There should be a business model for products with continued and repeated use, and another one for those that aren’t going to last more than a couple of years or have multiple owners. It’s about producers extending their responsibilities and having a plan for each.

“The future model will be around scarcity”

AB: This will put constraints on the materials you use, the way you design, the engineering of the products, so they can be dismantled easily, and that the sizing will be extendable to other people. And you will have to account for all that in your strategy. But the more you can extend the life of a product, the more value or equity you can extract from it.

Sounds like a tall order…

CB: To really see change in the marketplace, it takes time and long-term investment. You’re talking about a two-year project minimum, because you may have to create the supply yourself. It takes three years for a farmer to transition from conventional to organic, and they have to be supported in that transition.

AB: Doing all this is going to take some profit out of the system. There will be price increases, not just owing to inflation because of the war and the higher prices of oil, gas and petrol, but if you want to make products more transparent, you need to pay fair wages, track exactly where things are coming from, and this needs to be built into your business model.

The future model will be about producing just the right amount instead of overproducing and generating a lot of waste; the future model will be around scarcity. We created this problem – selling products for €1 and letting consumers think that was the right price, without any thought to the negative externalities – and now we have to try to solve it.

But it is solvable. Twenty years ago, nobody thought you could buy a product without trying it on first, and we all know how e-commerce has upended that. Now if people are prepared to buy a garment without actually trying it on, why not a product that is used but in good condition? Reselling is going to be part of the business model in the future.

In so many aspects, we need to radically rethink the retail model and extend the value that we can extract from the customer relationship in ways we never thought possible before.

Adapt or perish

05Retail Revolution

If the No. 1 priority for retailers during the height of the pandemic in 2020 was to stay open, since 2021 it has been how many shops to keep open and where.

“The pandemic’s most enduring feature will be as an accelerant of existing trends,” writes NYU Stern professor Scott Galloway. And one of those trends is what Galloway terms “the Great Dispersion.” Remember the way we used to work 9 to 5, Monday to Friday, and save up shopping for the weekend? We’d make a big trip to a suburban mall or superstore – places referred to as shopping “destinations.” Now, work, shopping and entertainment have been dispersed, unbundled from the constraints of time and place. Faced with this post-pandemic reality, I concur with Galloway that “all brands need to establish a direct relationship with the consumer.” What does that mean?

Innovation. In inflationary times, retailers want to keep their costs under control, so they may prefer not to launch their own brands or experiment with new products. But the crisis has shown that cash-strapped customers who switched to private labels will stay loyal if there is quality. Retailers must balance being conservative in the short term with attracting customers with innovative offers that generate loyalty over the long term.

Inflation. As 2020 supply-chain disruptions led to higher costs in 2021, retailers initially took the hit, especially those who had spare stocks, and consumers didn’t perceive those inflationary rises right away. Not anymore. In 2022 retailers are passing those costs on and prices are going up across categories. This is leading to a decline in spending, and recession. By now, retailers should have made their cost-price adjustments, but how long will consumers put up with paying more? Sales volumes are falling. Again, brands that are able to innovate and differentiate themselves – at affordable prices – will be better positioned to ride this cycle out. And eventually, when the Ukrainian crisis gets resolved, the effect on the global economy may be similar to the rebound after vaccines were introduced.

The trend of deglobalization is ongoing, reinforced by geopolitical tensions

Localization. Over the past two years, retailers that were able to shift their sourcing locally did so to avoid global supply-chain disruptions. This trend of deglobalization is ongoing, reinforced by geopolitical tensions and resurgent nationalism, as well as the drive to reduce carbon footprints. Localization, however, also has to do with the convenience of shopping locally – the dispersion or unbundling of demand mentioned earlier. People want things nearby. They may buy things online, but they want to see, touch and pick them up locally. Recognizing the desirability of local spaces, the suburban superstores are moving back into the neighborhood. And the larger chains need to decide if it’s really necessary to maintain two or three stores on the same shopping street: what might those become instead?

Omnichannel. The answer is to turn surplus stores into redesigned retail spaces. Whereas people used to discover brands online and then go to the store to buy them, now they tend to buy online and use the store to discover and try out new brands. The rise of e-commerce doesn’t eradicate the need for physical stores but rather reinvents them: they are the best way to create brand awareness and shift logistics costs over to the customer. So, these stores become warehouses, showrooms, experience centers, local collection points for online operations, or even dark kitchens. The latter is a trend that has taken off in the realm of food delivery, where food is prepared to order exclusively for delivery via third-party apps to customers living in close radius.

Direct-to-consumer (DTC). Selling via Amazon may expand your reach, but you don’t reap the rich customer data or control the sales process. To be profitable, at least half of your e-commerce should be direct-to-consumer, meaning selling directly to consumers via your own platform. Granted, you may still need to use local stores for delivery/pickup, so some of the gains of cutting out the middlemen are lost by doing your own logistics. But, on balance, DTC gives you better control over your margins and your customer relationships.

In this “never normal” world, retailers must get to grips with this permanent state of disruption. Some of the actions taken to cope with the pandemic – more open-air spaces, pickup zones, spaces redesigned for less crowding and better flows – demonstrate retailers’ quick thinking and are worth keeping. Retailers should build on this spirit of flexibility and resilience. Because there’s only one normal in business: Adapt or perish.

José Luis Nueno is an IESE professor of Marketing and holder of the Intent HQ Chair on Changing Consumer Behavior. He is the author of numerous books, including Never Normal (2022) and Direct to Consumer (2020).

This Report forms part of the magazine IESE Business School Insight 162. See the full Table of Contents.

This content is exclusively for individual use. If you wish to use any of this material for academic or teaching purposes, please go to IESE Publishing where you can obtain a special PDF version of this report as well as the full magazine in which it appears.